Walt Whitman's Brooklyn: In the Footsteps of the Borough's Bard

By Zac ThompsonWalt Whitman was Brooklyn’s original bearded bohemian. Though the poet was born on Long Island and spent significant portions of his life in Manhattan, Washington, D.C., and Camden, New Jersey, it was scrappy, part-rustic, part-industrialized mid-19th-century Brooklyn—at the time, a separate municipality from New York City—that shaped Whitman, particularly in the years leading up to the 1855 publication of his Leaves of Grass, the volume with which American poetry found its voice.

Visiting the writer’s old haunts feels especially appropriate in Whitman’s case, given the importance that his exuberant verse put on embracing strangers across divides of class, race, gender, geography, and time. "I am with you, you men and women of a generation, or ever so many generations hence," he writes in "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry." "Just as you feel when you look on the river and sky, so I felt." Which kind of sounds like he knew you’d take this tour.

And so, o sneaker-wearing sojourner, take me by the hand and follow through countless crowds of ample Brooklyn—borough of underemployed DJs and artisanal cheese shops we sing! Walt stops somewhere, waiting for you.

The Brooklyn Bridge was completed in 1883, long after Whitman had left town. In his day, the same portion of the East River—between, as he put it, the “tall masts of Mannahatta” and the “beautiful hills of Brooklyn”—was traversed by the Fulton Ferry. At the former disembarkation point on the east end of the bridge, lines from the poet’s “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” have been cut out of the riverside railings so that they look like subtitles for the view of Lower Manhattan. “Frolic on, crested and scallop-edg’d waves!” Whitman exults. “Throb, baffled and curious brain!”

After admiring that vista, do an about face and, with Manhattan behind you, tax your own baffled and curious brain to picture the once-grimy Brooklyn waterfront as it looked circa 1850, more than a century before the shipyards and factories had been repurposed for the restaurants, luxury apartments, and tourist-friendly amenities of today.

Now turn right and follow the footpath through Brooklyn Bridge Park, past floating classical venue Bargemusic, skyline lookout the Granite Prospect (where a marathon reading of Whitman’s “Song of Myself” is held each June), sport courts, picnic areas, and stretches of green (look for Lady Liberty in the distance across the water to your right), until you reach Pier 5 and our next stop.

It’s never too early in a walking tour for an ice cream break—and this one has a Whitman connection. Ample Hills Creamery, which has a seasonal outpost at Brooklyn Bridge Park and several other locations throughout the city, takes its name from another line in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”: “. . . Brooklyn of ample hills was mine.” Seems like a good excuse to buy a cone of something frozen and sweet, plop down on a park bench, and indulge in the very Whitmanesque pastime of watching the diverse crowd stream past. On a recent visit, we spotted Spanish-speaking picnickers, a yarmulke-sporting father and son on a stroll, and a Bible study group composed of Asian-American twentysomethings. As Whitman wrote in “City of Ships”:

City of the world! (for all races are here,

All the lands of the earth make contributions here)

Once you’ve had an eye- and bellyful, retrace your steps back to Old Fulton Street and take a right. After two blocks, stop at the fortresslike red-brick building on your right.

From 1841 to 1892, this was the site of the Brooklyn Eagle newspaper, which hired a 26-year-old Walt Whitman as editor in 1846. He churned out a daily deluge of reportage, arts criticism, personal essays, and editorials advocating for the rights of women and laborers as well as fiery polemics against slavery. After only two years, the paper’s owners fired him for political differences. The Eagle’s offices were torn down in the 1890s and replaced with a warehouse designed by architect Frank Freeman to look like a medieval bastion in brick. As with many New York landmarks, the building now houses ultra-expensive condos. A plaque out front details Whitman’s link to the address.

Now continue walking away from the waterfront along Old Fulton Street, which curves rightward and becomes Cadman Plaza West. Keep going until you reach Cranberry Street on your right, facing a leafy park across the street.

You’d never know it today, but one of the most important volumes in American verse was published right here. In 1855, the Rome Brothers Print Shop put out the first edition of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass—paid for by the author, who also did some of the typesetting. Sales were nil, but Whitman continued to expand and revise the book for the rest of his life, and later editions gained in popularity, in part due to some well-timed recommendations from Ralph Waldo Emerson and others, as well as a degree of controversy stirred up by the poems’ frank celebrations of the body and same-sex desire. By the middle of the 20th century, Leaves of Grass was recognized as the wild masterwork it is, a literary equivalent to the Grand Canyon.

And the site where this world-changing barbaric yawp was first sounded? The property is now occupied by a couple of drab modernist apartment buildings. Instead of lingering, you’re better off crossing the street and entering Cadman Plaza Park (pictured above), where you can at least look at some actual leaves of grass.

With Cranberry Street behind you, cut through the park to reach our next stop.

Given this area’s pivotal role in Whitman’s career, it’s fitting that he has his own city park named after him here. The centerpiece is a fountain that shoots jets of water up from a granite surface—the sort of thing that kids and dogs like to run through on a hot day. Quotes from four of Whitman’s poems are inscribed along the perimeter. As you make the circuit, you might be struck by how relevant his words still are, such as this hashtag-ready advice from “To the States”: “Resist much, obey little.”

If that doesn’t put you in too rebellious a mood to continue following our directions, cut back through Cadman Plaza Park and cross the street to reach the High Street–Brooklyn Bridge subway station. Take a C train toward Euclid Avenue (not to Manhattan) and ride three stops, getting off at Lafayette Avenue.

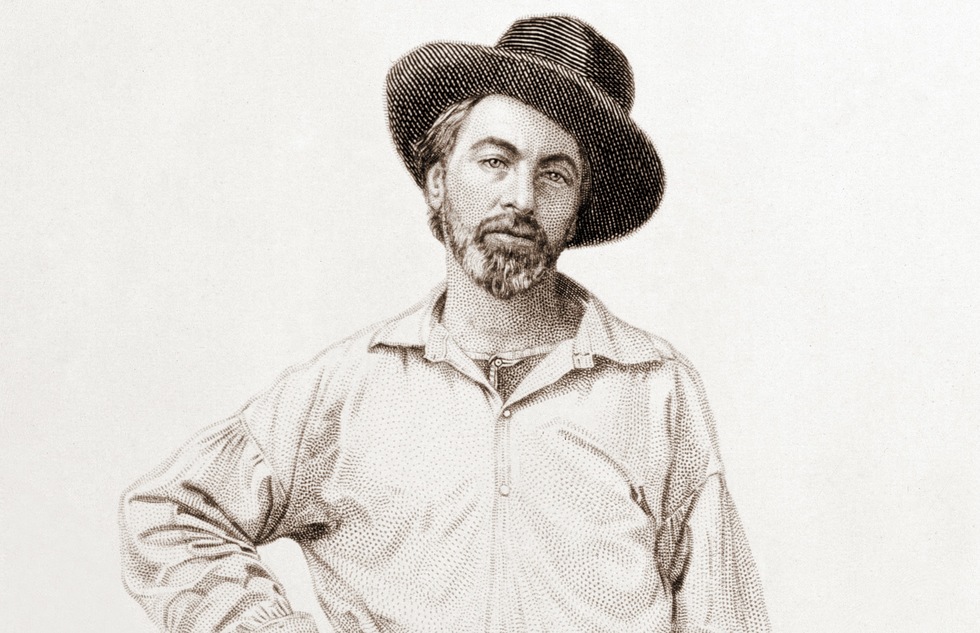

From the Lafayette subway stop, take a five-minute walk north between classic Brooklyn brownstones on Cumberland Street until you come to Dekalb Avenue. On the southwest corner (on your left before you cross the street), you’ll find Walter’s, a good spot for brunch or a classic cocktail served by a bowtie-wearing bartender. The eatery is a spinoff of Walter Foods up in the neighborhood of Williamsburg—so it’s not technically named after Whitman. But Walter’s does have a wall o’ Walts showcasing framed black-and-white photos of famous Walts and Walters, including you-know-who (in the brown frame pictured above) as well as Messrs. Disney, Matthau, Cronkite, and Payton. The menu features hearty American staples and seafood, both of which also fit with our theme. We regret to inform you, however, that you’ll look in vain for dishes with names like Leaves of Grass-fed Beef or Song of My Shellfish.

Just across the street from Walter’s stretches Fort Greene Park, 30 acres of rolling green space that owes its official designation as public property in large part to Walt Whitman. The site of a Continental Army post during the American Revolution, the grounds were later used to bury the 11,500 colonial “prison ship martyrs” who died from disease and malnourishment while held as prisoners of war aboard British ships in Wallabout Bay to the north. By the time Whitman began editing the Brooklyn Eagle in 1846, the peaceful property seemed to him ideal as “a place of recreation . . . where, on hot summer evenings, and Sundays, [urban dwellers] can spend a few grateful hours in the enjoyment of wholesome rest and fresh air.”

His tireless advocacy of the project via frequent editorials helped garner public support and convince officials to make this spot a park in 1847. Later, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux—of Central Park fame—designed the landscaping, and, later still, a 149-foot Doric column (pictured above) designed by scandal-prone architect Stanford White was installed to honor the prison ship martyrs. Few plots of land have been associated with such an all-star cast of American icons, yet the vibe is as calm and pastoral as Whitman envisioned.

If you walk through Fort Greene Park to its northern end, you’ll hit Myrtle Avenue, home of a public housing project named after Whitman. Turn right on Myrtle and you’ll witness firsthand the creep of gentrification, as humble laundromats and taquerias neighbor newer wine shops and condo buildings.

When you get to Ryerson, take a left and continue about 400 feet to No. 99 (on your right), a nondescript, three-story house covered in beige siding (it's the one with the white door in the picture above). Whitman lived here when Leaves of Grass was published in 1855—in fact, it’s the only one of his Brooklyn residences that’s still standing. The poet's fans and scholars have lobbied the city to get landmark status for the privately owned building, but so far to no avail. Seems like somebody could at least put up a sign.

Does an unmarked house feel like an anticlimax? For poetic symmetry, you can end your Whitman tour where we started—with words on a railing—by crossing into Lower Manhattan. Take an Uber or backtrack to the subway to reach the waterfront plaza at Brookfield Place (230 Vesey St.; commonly known by its original name, the World Financial Center), a shopping and dining complex near the World Trade Center. With the Hudson River as a backdrop, block letters spell out lines from Whitman's “City of Ships” that can serve as a coda for our journey:

City of wharves and stores—city of tall facades of marble and iron!

Proud and passionate city—mettlesome, mad, extravagant city!