Paris is a city for walkers. One lovely neighborhood after another unfolds along its sidewalks, punctuated by plazas and monuments that are best experienced at ground-level. At every turn there seems to be an intriguing area that begs to be explored.

The Right Bank

LOUVRE & ÎLE DE LA CITÉ

Best for: Museums, historic sights, architecture, transportation hubs

What you won’t find: Evening entertainment, quiet streets

Parameters of the neighborhood: 1st arrondissement & part of the 4th

This is the heart of the city, and the oldest part of Paris, though you’d never know it to see it now. In the 19th century, Baron Haussmann, Napoleon’s energetic urban planner, tore down almost all of the medieval houses that once covered this area. The Île de la Cité is where the city first emerged after Gallic tribes started camping out here in the 3rd century B.C. By the 1st century A.D., the Romans were building temples, and by the Middle Ages, a mighty fortress sat across the river on the Right Bank. The fortress has long since been incorporated into the majestic buildings of the Louvre, which along with the Jardin des Tuileries takes up a big chunk of the neighborhood (you can see vestiges of it—the old stone foundations—in the Carousel du Louvre, an underground shopping mall set below the museum). Today, the Ile is mostly visited for the soaring Cathedral of Notre-Dame and the gemlike St-Chapelle, along with the historic Conciergerie.

While the major museums and sites are to the west, the people’s part of this neighborhood is on its eastern edge, near Les Halles (the city’s former food market) and place du Châtelet. Parisians descend on this area for their shopping needs, particularly along the bustling rue de Rivoli and around the newly remodeled Forum des Halles mall and park. When the covered food market was demolished and relocated to the suburban town of Rungis in the 1970s, Les Halles lost its charm—and unfortunately, despite its multimillion-euro refurbishment, it’s still not particularly picturesque, but it is a hotspot for high-street boutiques and late-night bistros. During the day the area’s very safe—if not a little overcrowded—but avoid its Châtelet-les-Halles RER station late at night when troublemakers sometimes hang out. The same is true of the seedy rue St-Denis, just to the east, as this is one of Paris’s red-light districts.

OPERA & GRANDS BOULEVARDS

Best for: Good restaurants, covered passages, boutiques

What you won’t find: Monuments (with the exception of the Opéra Garnier) and museums, green spaces

Parameters of the neighborhood: 2nd & 9th arrondissements

When the Grands Boulevards were plowed through the city in the 19th century (see box above), they created a new opportunity for stylish Parisians to stroll, see, and be seen, while theaters and cafes flourished. Times changed and so did fashion, and for decades this area was considered a has-been. In recent years, it's undergone a transformation, particularly in the 9th arrondissement, where cafes, boutiques, and restaurants have popped up in between the church of St-Georges and Place de Clichy, in an area that used to be known as “New Athens.” Many artists of the 19th-century Romantic movement, like George Sand and Eugène Delacroix, lived and worked here; the quaint Musée de la Vie Romantique is worth an hour’s visit, with beautiful trinkets, letters and drawings that once belonged to Sand. Today, those in the know call it SoPi (South of Pigalle), as entrepreneurial Parisians have begun opening trendy bakeries, shops, and restaurants.

The 9th is also the home of the Grand Magasins (big-name department stores), which are located on boulevard Haussmann near Gare St-Lazare, as well as the grandiose Palais Garnier, home of the Opéra de Paris. An important monument in the 2nd arrondissement is the neo-classical Palais Brogniart, built between 1808 and 1813 on place de la Bourse to house the city’s former Bourse, the French stock exchange. To the east, the trendy set descends on rue Montorgueil, a picturesque, cobbled market street, and the pedestrian area around rue Etienne Marcel, which has gained a reputation as a hip fashion district. This also is the arrondissement with the greatest concentration of passages, the 19th-century covered shopping arcades that were the forefathers of today’s shopping malls (but much prettier; see “Arcades”).

THE MARAIS

Best for: Restaurants, nightlife, window shopping, 17th-century mansions, museums

What you won’t find: Bargain shopping, iconic sights, open spaces

Parameters of the neighborhood: 3rd & 4th arrondissements

What was once marshy farmland (marais means “marsh” or “swamp”) quickly became a seat of power when the Knights Templar decided to build a fortress here in the Middle Ages. Other religious orders followed suit, and after King Charles V built a royal residence here in the 14th century, the ensuing real-estate boom produced a slew of mansions and palaces. In the 17th century, King Henri IV created a magnificent square bordered by Renaissance-style townhouses, today called the Place des Vosges. If the Marais was hot before, then it was positively on fire. Nobles and bourgeois pounced on the neighborhood, each one trying to outdo the other by constructing more and more resplendent hôtels particuliers, or private mansions.

But by the time the Revolution flushed out all its aristocrats in the 18th century, the overstuffed quarter was already falling out of fashion. The magnificent dwellings were abandoned, pillaged, partitioned, and turned into stores, workshops, and even factories. The new residents were working class, with more immediate concerns than saving historic patrimony. The neighborhood fell into disrepair, and periodic attempts on the part of the city to “clean up” unfortunately resulted in the destruction of many architectural gems.

The area underwent a real renovation in the 1960s, and today several of the most magnificent mansions have been restored and are open to the public in the form of museums such as the Carnavalet, Musée Cognac-Jay, and the Musée Picasso. The architecturally odd Centre Pompidou is also located here.

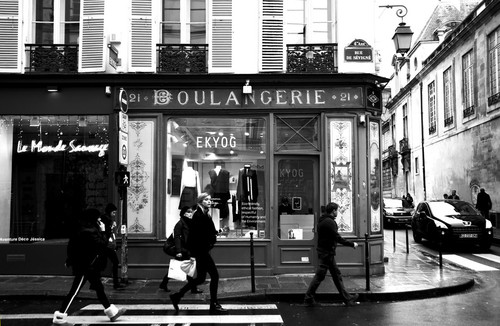

Today the area is terribly branché (literally, “plugged in”), and you’ll see some of the hippest styles in boutique windows here, as well as dozens of happening restaurants and bars lining the narrow streets. The neighborhood remains a mix, though—jewelry and clothing wholesalers bump up against stylish cafes and shops. The vibrant gay scene on rue Vielle du Temple intersects with what’s left of the old Jewish Quarter on rue des Rosiers. The black and white photo at the top of the page captures the spirit of this neighborhood.

CHAMPS-ÉLYSÉES, TROCADÉRO & WESTERN PARIS

Best for: Serious strolling (on the Champs-Élysées, pictured above), museums, monuments, chic restaurants, and stores

What you won’t find here: Affordable eateries or hotels, regular folk

Parameters of the neighborhood: 8th, 16th & 17th arrondissements

The Champs-Élysées cuts through this area like an asphalt river—it’s the widest boulevard in Paris. Crossing the street here feels a bit like traversing a raging torrent (be sure to wait for the light). This epic roadway has its fans and foes. Some find its lights and sparkles good clean fun, while others dismiss it as crass and commercial. No matter how you may feel about the street itself, you’re bound to be impressed by the Arc de Triomphe, which lords over the boulevard from its western tip. To the south of the Champs are some of the most expensive stores, restaurants, and homes in the city (particularly around av. Montaigne). This is also where you’ll find the new Musée Yves Saint Laurent, dedicated to the couturier’s life and career. To the north, a largely residential area extends up to the beautiful Parc Monceau, which is surrounded by some equally delightful museums, such as the Musée Jacquemart-André and the Musée Nissim de Camondo.

To the west, the illustrious Seizième (sez-ee-em, 16th arrond.), is the most exclusive arrondissement of the city. Lying on the outer western edge of the city, this residential area is packed with magnificent 19th-century residences and apartment houses, as well as many fine parks and gardens. In fact, the arrondissement shares its western border with the Bois de Boulogne, one of the city’s two huge wooded parks. While the 16th is not known for its liveliness, it is graced with a terrific array of museums. The Palais de Chaillot shelters the Cité de l’Architecture and the Musée de l’Homme, just down the street is the vast Musée National des Arts Asiatiques Guimet, and a little farther on there are two modern art museums in the Palais de Tokyo, not to mention a half-dozen others, like the Marmottan, sprinkled around the arrondissement. And a stop at the esplanade on the Place du Trocadéro is a must. Between the two wings of the Palais de Chaillot is a superb view of the Eiffel Tower, which you can walk to by strolling down the hill through the Jardins du Trocadéro.

MONTMARTRE

Best for: Restaurants, nightlife, atmosphere

What you won’t find here: Monuments (with the exception of Sacré-Coeur), major museums, grand architecture

Parameters of the neighborhood: 18th arrondissement

Once a village overlooking the distant city, Montmartre is now as inseparable from Paris as the Eiffel Tower, which means it’s a major target for the tour-bus crowd. And crowded it is, especially in the area immediately around the Basilica of Sacré-Coeur and the overdone place du Tertre. Yet, if you wander around the cobbled streets (see above) that surround place des Abbesses, you’ll find plenty of hip boutiques and cute restaurants frequented by an upwardly arty crowd, who have also staked out territory in the working-class neighborhoods immediately east and north of the basilica.

Farther east is the lively immigrant quarter of Barbès, home to large communities from sub-Saharan Africa, the Maghreb (North Africa), and India. Here you’ll find a jumble of inexpensive stores selling everything from long-necked teapots to pajama-like salwar trousers, as well as tiny restaurants that offer exotic delicacies.

RÉPUBLIQUE, BASTILLE & EASTERN PARIS

Best for: Nightlife, good restaurants, Revolutionary history, arty boutiques

What you won’t find here: Major monuments and museums, high-end shops

Parameters of the neighborhood: 11th & 12th arrondissements

These two arrondissements were pretty much off the tourist radar until 1989, when the new Bastille opera house provoked an explosion of bars and restaurants in the surrounding streets. Though the shine has already worn off the nightspots of rue de Lappe (pictured above) and rue de la Roquette (just off the Place de la Bastille), the nocturnal life of the 11th arrondissement is far from dull, as new clubs and cafes have opened farther north on rue de Charonne and rue Oberkampf. Now even Oberkampf has become thoroughly saturated, and intrepid partyers are staking out new ground in Ménilmontant in the 20th.

North of the Place de la Bastille is the vast pedestrian-friendly place de la République. To the east is the Faubourg St-Antoine, a historic workers’ quarter inhabited by woodworkers and furniture makers since the 13th century. After a few centuries, the density of underpaid, overburdened workers made St-Antoine a breeding ground for revolutionaries. The raging mob that stormed the Bastille prison in 1789 originated here, as did those of the subsequent uprisings of 1830, 1848, and the Paris commune.

In recent years, the area has become a magnet for foodies, as young chefs have opened some of the city’s most exciting restaurants, like Septime on rue de Charonne. While the architecture here is nowhere near as grand as elsewhere in Paris, the neighborhood has retained an authenticity that’s rarely found in the more popular parts of the city. A large number of furniture stores and ébénistes (woodworkers) are tucked into large interior courtyards accessible by covered passages off rue du Faubourg St-Antoine. Make a point of wandering down one of these; you’ll be rewarded with a look at a way of life that has survived the centuries. This quarter extends all the way past the Viaduc des Arts to the Gare de Lyon train station, a magnificent example of Belle Epoque architecture. At the western end is the Bois de Vincennes, one of the city’s two wooded parks.

BELLEVILLE, CANAL ST-MARTIN & NORTHEAST PARIS

Best for: Nightlife, restaurants, strolling (along the canal), arty boutiques

What you won’t find here: Major monuments, museums, and architectural wonders

Parameters of the neighborhood: 10th, 19th & 20th arrondissements

For a long time, no one seemed to care about these arrondissements. They were too far from the center of the city, too working-class to be of interest to the trendy set, and too monument-less to appeal to tourists. Then, with real estate skyrocketing, young professionals and artists began to move in. Suddenly, the forgotten Canal St-Martin was blooming with cafes and restaurants and the streets around it were full of trendy shops. Artists looking for studio space discovered multi-ethnic Belleville, a cultural melting pot of immigrants from North Africa (both Jewish and Muslim), Asia (this is Paris’s second biggest Chinatown), and other parts of the world. The vast park and cultural venues of La Villette have also attracted new interest away from the center. Happily, these areas aren’t really gentrified (yet), and parts are infused with a certain youthful energy that’s hard to come by in other areas. Relatively tourist-free, these districts offer an opportunity to see a more local side of the city.

Aside from the Parc de la Villette, there are two other green havens here: the Parc des Buttes Chaumont and the Père-Lachaise Cemetery, where the likes of Jim Morrison, Edith Piaf, and Chopin are buried. Several good bars and music venues are around Ménilmontant to the north of the cemetery and around place St-Blaise to the south.

The Left Bank

LATIN QUARTER

Best for: Affordable dining, student bars, art-house movie theaters, museums, Jardin des Plantes

What you won’t find here: Good shopping, quiet (at least not in the environs of pl. St-Michel)

Parameters of the neighborhood: 5th arrondissement

Since the Middle Ages, when the Sorbonne and other academic institutions were founded, this has been a student neighborhood. (It earned its name as the “Latin” Quarter because back in the old days, all classes were taught in Latin.) Today the area still harbors the highest number of colleges and universities in the city, and you’ll certainly see plenty of students and professors hanging around the restaurants and cafes here. You’ll also see plenty of tourists, who tend to swarm the warren of tiny streets that lead off the place St-Michel. Avoid rue de la Huchette (except for the great swing-dancing club, Le Caveau de la Huchette, which is lined with garish restaurants of questionable quality. Boulevard St-Michel, a legendary artery once lined with smoky cafes filled with thinkers and rabble-rousers, has now fallen prey to chain stores, though a few big bookstores have held on. The boulevard also harbors the Musée de Cluny, a terrific collection of medieval art and Roman ruins.

For a more authentic taste of this neighborhood, wander east and upward, around the windy streets on the hill that leads to the Panthéon, the church of St-Etienne-du-Mont (pictured above) and around rue Monge, toward the lovely Jardin des Plantes. Surrounded by the city’s natural history museum, this botanical garden is a wonderful place to relax. Down by the Seine, the museum of the Institut du Monde Arabe is housed in a spectacular building by architect Jean Nouvel.

ST-GERMAIN-DES-PRÉS & LUXEMBOURG

Best for: Fine dining, historic cafes, shopping, parks (the Jardin du Luxembourg)

What you won’t find here: Penniless intellectuals and artists, low prices

Parameters of the neighborhood: 6th arrondissement

The church of St-Germain-des-Prés, the heart of this neighborhood, got its name (St. Germain of the Fields) because when it was built in the 11th century, it was in the middle of the countryside. What a difference a millennium makes. The church became the nucleus of a huge and powerful abbey, which would later constitute an autonomous minicity complete with a hospital and a prison. The Revolution cut the church down to its current size, and an elegant collection of apartment houses, squares, and parks grew up around it, making it one of Paris’s most appealing areas to live in (as real-estate prices will attest). If the neighborhood has always had aristocratic airs (it was a favorite haunt of the nobility during the 17th and 18th c.), during the last part of the 19th century up to the mid–20th century it was also a magnet for penniless artists and intellectuals, who hung out in legendary cafes like the Café de Flore and Les Deux Magots.

Today few struggling creative types can afford either the rents or the price of a cup of coffee around here, and young artists and thinkers have moved north and east to cheaper parts of town. Though the ambience is decidedly bourgeois these days, the neighborhood is still dynamic, and the cafes and shops along the boulevard St-Germain are crowded with a mix of politicians, gallery owners, French celebrities, and editors. This is also a fun neighborhood for shopping—from 500€ pumps on chic rue des St-Pères to 30€ sundresses on the more plebian rue des Rennes. And when you’ve tired yourself out, you can stroll over to the magnificent Jardin du Luxembourg for a timeout by the fountain.

EIFFEL TOWER & LES INVALIDES

Best for: Iconic monuments, majestic avenues, grand vistas, museums

What you won’t find here: Affordable restaurants or shopping, nightlife

Parameters of the neighborhood: 7th arrondissement

The Eiffel Tower reigns over this swanky arrondissement, where the streets that aren’t lined with ministries and embassies are filled with elegant apartment buildings and prohibitively expensive stores and restaurants. A large portion of the neighborhood is taken up by the Champs de Mars, a park that stretches between the tower and the Ecole Militaire, and by the enormous esplanade in front of the Invalides, which sweeps down to the Seine with much pomp and circumstance. Some of the city’s best museums are around here, including the Musée d’Orsay, the Musée Rodin, and the Musée du Quai Branly, whose wacky architecture has added some spice to this very staid area.

While this neighborhood certainly has a lot to see, it is a little short on human warmth—this is not the place to come to see regular Parisians in their natural habitat. One exception is the area around the pedestrian rue Cler, a market street that is home to many delightful small restaurants and food stores. Word is out about this cozy corner, however, so expect to see plenty of tourists when you go into that cute boulangerie for a couple of croissants.

MONTPARNASSE

Best for: Shopping, historic cafes, nightlife

What you won’t find here: Extraordinary architecture, museums, monuments

Parameters of the neighborhood: 14th & 15th arrondissements

In the early 1970s, government officials decided the time had come to make Paris a modern city. Blithely putting aside concerns for historic patrimony and architectural harmony, the old Montparnasse train station and its immediate neighborhood were torn down and a 56-story glass tower and shopping complex was erected in its place. A new train station was constructed behind the tower, as well as a barrage of modern apartment buildings and offices. Fortunately, even ugly contemporary architecture didn’t manage to kill the neighborhood—at the foot of the Tour Montparnasse, life goes on as it always has. A few steps away from the station, stores and cafes still line the tiny old streets; you’ll also find many crêperies (crêpe restaurants), an outgrowth of the large Breton (that is, from Brittany) community that still inhabits this area. Farther down boulevard Montparnasse, you’ll find legendary brasseries such as La Coupole and Le Select, where Picasso, Max Jacob, and Henry Miller used to hang out in the 1920s. For a bit of calm, take a walk around the Cimetiére de Montparnasse, where artists such as Charles Baudelaire and Constantin Brancusi are buried. In the evenings, crowds pour into the many restaurants and movie theaters around the station.

To the south, the arrondissement takes a more residential turn, with the exception of rue Daguerre, a lively market street a block south of the cemetery, and farther south, rue d’Alésia, a discount shopper’s mecca. The 14th is also home to Les Catacombes, former limestone mines lined with the bones of millions of Parisians whose remains were moved here in the 18th century when the city’s overcrowded graveyards became unhygienic. It makes for a spooky (and intriguing) visit.

A word on how the Paris we see today came to be

The Paris you see before you was radically transformed in the late–19th century by a pugnacious urban planner named Georges-Eugène Haussmann. Before Haussmann got his hands on it, Paris was a mostly medieval city of tiny streets and narrow alleyways—and major sanitation problems. Everyone agreed that something needed to be done to facilitate traffic and clean up the city, but no one managed to come up with a solution.

Enter Baron Haussmann. Named prefect of the Seine by Napoleon III, Haussmann pushed through wide boulevards (Malsherbes, Haussmann, and Sebastapol, among others), demolished dozens of old neighborhoods, and encouraged promoters to build new buildings, following, of course, his strict rules on the style of the facades and the height of the structures. The result was the elegant Haussmannian architecture that lines most of the city’s streets, as well as the system of central arteries that collect in star-shaped intersections at various points. The boulevards were strategically placed—one of the reasons for their creation was to make it easier to crush rebellions in the worker’s quarters, and garrisons were set up at crucial intersections. Streets were also now too wide in most areas to be easily barricaded. Haussmann also accessorized his new neighborhoods and streets; the famous kiosks, benches, and lampposts you see around the city today date from this epoch.

While there’s no denying that his projects improved traffic, sanitation, and security and gave a pleasing architectural unity to the cityscape, Haussmann’s take-no-prisoners approach has been criticized for having neutered the personality of entire neighborhoods (the Île de la Cité, for example, was almost entirely razed) and destroying important historical buildings.

Note: This information was accurate when it was published, but can change without notice. Please be sure to confirm all rates and details directly with the companies in question before planning your trip.