8 Italian Masterpieces That Barely Survived

By Donald Strachan

War after war, occupation followed by revolution, bad luck combined with bad judgment -- all have contributed to the destruction of Italy's art treasures. A fire in the Sala del Scrutinio and the Sala del Maggior Consiglio in Venice's Doge's Palace destroyed several Titians as well as work by Bellini, Gentile da Fabriano, and Pisanello. A half-crazed Botticelli tossed several of his own "decadent" works onto the Bonfire of the Vanities in 1497.

Italian art has, unfortunately, not been immune from the turbulent influence of the peninsula. But the history of Italian art and architecture isn't short of happy endings, either. Many works we admire today have dodged a bullet or two during the journey to the 21st century.

Here are eight masterpieces that narrowly averted destruction and how each survived to see another day.

Photo Caption: Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy.

Courtesy Vito Arcomano © Fototeca ENIT

Italian art has, unfortunately, not been immune from the turbulent influence of the peninsula. But the history of Italian art and architecture isn't short of happy endings, either. Many works we admire today have dodged a bullet or two during the journey to the 21st century.

Here are eight masterpieces that narrowly averted destruction and how each survived to see another day.

Photo Caption: Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy.

Courtesy Vito Arcomano © Fototeca ENIT

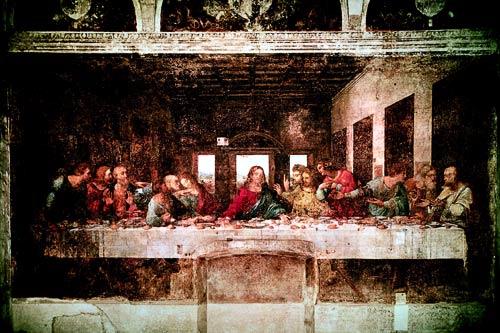

"Last Supper" at Milan's Santa Maria Delle Grazie

What: Thanks to Dan Brown's novel (and then Tom Hanks' film), The Da Vinci Code, Leonardo da Vinci's "Last Supper" was thrust into the lives of those who hadn't already heard of it. The theme of the Cenacolo was a common enough one in the Renaissance decoration of convent refectories. But the great Florentine polymath imbued his version, painted in the 1490s, with extraordinary movement and dynamism.

Where: Santa Maria Delle Grazie, Milan (tel. 02-92800360; www.cenacolovinciano.net).

How: As well as a being genius, da Vinci was an inveterate tinkerer and experimenter. On this occasion, it was to the detriment of his work. Within a decade or two, the paint was peeling because he'd applied it dry and not in the true fresco style (which involves painting onto wet plaster). It's been a constant battle since to save it. While it's damaged, washed-out and not as da Vinci would have wished us to see it, even a 1943 bomb that took out most of the rest of the refectory couldn't destroy it. Or its popularity: you'll need to book your visit slot way ahead of your arrival.

Photo caption: Detail of Leonardo da Vinci's "Last Supper".

Courtesy De Agostini Picture Library.

Where: Santa Maria Delle Grazie, Milan (tel. 02-92800360; www.cenacolovinciano.net).

How: As well as a being genius, da Vinci was an inveterate tinkerer and experimenter. On this occasion, it was to the detriment of his work. Within a decade or two, the paint was peeling because he'd applied it dry and not in the true fresco style (which involves painting onto wet plaster). It's been a constant battle since to save it. While it's damaged, washed-out and not as da Vinci would have wished us to see it, even a 1943 bomb that took out most of the rest of the refectory couldn't destroy it. Or its popularity: you'll need to book your visit slot way ahead of your arrival.

Photo caption: Detail of Leonardo da Vinci's "Last Supper".

Courtesy De Agostini Picture Library.

Giotto's Frescoes at Scrovegni Chapel, Padua

What: So delicate and precious are the frescoes of the Scrovegni (or Arena) Chapel, painted by Giotto between 1303 and 1305, that visitors have to sit for 15 minutes in a decontamination chamber before entering the hallowed space. The barrel-vaulted chapel is completely covered in paint showing 38 scenes from the lives of Christ and the Virgin Mary, an apocalyptic "Last Judgment" over the exit door, as well as the first recorded grisailles, or monochrome allegories representing the 14 virtues and vices in human form.

Where: The Musei Civici Eremitani complex, in Padua (tel. 049-2010020; www.cappelladegliscrovegni.it).

How: Just about every near miss you can think of has threatened Giotto's decoration in the 705 years since its unveiling. The tiny chapel once formed part of a larger palazzo that was torn down. An exterior porch collapsed in the 1800s, filling the room with noxious dust. Flying Fortresses rained bombs down on the city during the German occupation. (And if you want to see what a direct hit from a World War II bomb can do to a fresco, you need only sneak next door for a weep at Mantegna's Ovetari Chapel. Once the pride of the Eremitani Church, a stray British bomb on the night of March 11, 1944, reduced it to a few jigsaw-size pieces of painted plaster glued over a black-and-white photostat.

Photo Caption: The interior of Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy.

Courtesy De Agostini Picture Library

Where: The Musei Civici Eremitani complex, in Padua (tel. 049-2010020; www.cappelladegliscrovegni.it).

How: Just about every near miss you can think of has threatened Giotto's decoration in the 705 years since its unveiling. The tiny chapel once formed part of a larger palazzo that was torn down. An exterior porch collapsed in the 1800s, filling the room with noxious dust. Flying Fortresses rained bombs down on the city during the German occupation. (And if you want to see what a direct hit from a World War II bomb can do to a fresco, you need only sneak next door for a weep at Mantegna's Ovetari Chapel. Once the pride of the Eremitani Church, a stray British bomb on the night of March 11, 1944, reduced it to a few jigsaw-size pieces of painted plaster glued over a black-and-white photostat.

Photo Caption: The interior of Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy.

Courtesy De Agostini Picture Library

The Ruins of Pompeii

What: When the cockerel crowed on August 24, 79 A.D., the Roman town of Pompeii was a prosperous hub of commercial properties, homes for all social classes, and enough spas and brothels to satisfy the substantial Roman appetite for both. Dwellings such as the House of the Vettii and the Villa of the Mysteries were richly frescoed with mythological scenes and decorated with intricate mosaics. There was, we have since discovered, enough art on show to study and interpret three centuries of Roman painting.

Where: 16 miles southeast of Naples, in Campania (www.pompeiisites.org).

How: It's comforting to learn that not even one of Italy's most calamitous natural disasters managed to stop Pompeii's legacy. Over the course of 24 hours, the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius buried Pompeii in 60 feet of ash and red-hot pumice, rendering it uninhabitable. The same eruption buried the nearby, upscale Roman seaside resort of Herculaneum in an 1800°F torrent of pyroclastic mud, killing hundreds. Both towns were forgotten for 1,500 years until excavation began in the 18th century.

Photo Caption: The ruins of Pompeii, Italy.

Photo by Ted Holm/Frommers.com Community

Where: 16 miles southeast of Naples, in Campania (www.pompeiisites.org).

How: It's comforting to learn that not even one of Italy's most calamitous natural disasters managed to stop Pompeii's legacy. Over the course of 24 hours, the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius buried Pompeii in 60 feet of ash and red-hot pumice, rendering it uninhabitable. The same eruption buried the nearby, upscale Roman seaside resort of Herculaneum in an 1800°F torrent of pyroclastic mud, killing hundreds. Both towns were forgotten for 1,500 years until excavation began in the 18th century.

Photo Caption: The ruins of Pompeii, Italy.

Photo by Ted Holm/Frommers.com Community

Cimabue's "Crucifix" at Santa Croce, Florence

What: Centuries before Michelangelo and da Vinci, before Masaccio and even Giotto, Cimabue (pronounced chee-ma-boo-eh) was the acknowledged star of Tuscan art. His painting was the bridge between stylized Byzantine iconography and the "modern" work of his pupil, Giotto. His 1288 painted wooden "Crucifix" is one of only a handful of his works that survive.

Where: Hanging in the Refectory (now a museum) of Santa Croce, in Florence (www.santacroceopera.it).

How: To the English, it's the year they won the World Cup; to an American, the year Ronald Reagan was elected Governor or the year Walt Disney died. But to a Florentine, 1966 is the year of the Great Arno Flood. In early November, waters galloped down from the inundated Casentino and rose rapidly to a depth of 20 feet, drowning people as far from the riverbank as the Santa Maria Novella underpass. Thousands of tons of mud destroyed or damaged art on a massive scale, including Cimabue's "Crucifix." Although it survived, and is back on show after painstaking restoration, about 60 percent of its paint has been lost forever.

Photo Caption: Cimabue's wooden Crucifix hangs in the refectory of Santa Croce in Florence.

Photo by dvdbramhall/Flickr.com

Where: Hanging in the Refectory (now a museum) of Santa Croce, in Florence (www.santacroceopera.it).

How: To the English, it's the year they won the World Cup; to an American, the year Ronald Reagan was elected Governor or the year Walt Disney died. But to a Florentine, 1966 is the year of the Great Arno Flood. In early November, waters galloped down from the inundated Casentino and rose rapidly to a depth of 20 feet, drowning people as far from the riverbank as the Santa Maria Novella underpass. Thousands of tons of mud destroyed or damaged art on a massive scale, including Cimabue's "Crucifix." Although it survived, and is back on show after painstaking restoration, about 60 percent of its paint has been lost forever.

Photo Caption: Cimabue's wooden Crucifix hangs in the refectory of Santa Croce in Florence.

Photo by dvdbramhall/Flickr.com

Brancacci Chapel in Florence's Santa Maria del Carmine

What: The images painted between 1424 and 1428 on the walls of the tiny Brancacci Chapel heralded a new artistic age in Florence: the Renaissance. The various scenes from the life of St. Peter were a collaboration between Masaccio and Masolino (finished in the 1480s by Filippino Lippi), but it was specifically Masaccio's mastery of linear perspective and vivid human realism that artists -- including Michelangelo -- came to study a century later.

Where: In the right transept of Santa Maria del Carmine, in Oltrarno, Florence (tel. 055-2768224).

How: It only takes a quick look at the incongruous Baroque decoration of the nave and apse of this Carmelite church to see that something strange happened here. In fact, almost the entire building was destroyed by fire in 1771. Miraculously, the right transept escaped with a thorough soot-staining. Masaccio died when he was just 27, and along with his "Trinity" in Santa Maria Novella, the Brancacci frescoes are his most important bequest to Florence. Without one huge slice of luck, the greatest Florentine painter between Giotto and Michelangelo would be even more of a mystery.

Photo Caption: The interior of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence.

Courtesy Vito Arcomano © Fototeca ENIT

Where: In the right transept of Santa Maria del Carmine, in Oltrarno, Florence (tel. 055-2768224).

How: It only takes a quick look at the incongruous Baroque decoration of the nave and apse of this Carmelite church to see that something strange happened here. In fact, almost the entire building was destroyed by fire in 1771. Miraculously, the right transept escaped with a thorough soot-staining. Masaccio died when he was just 27, and along with his "Trinity" in Santa Maria Novella, the Brancacci frescoes are his most important bequest to Florence. Without one huge slice of luck, the greatest Florentine painter between Giotto and Michelangelo would be even more of a mystery.

Photo Caption: The interior of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence.

Courtesy Vito Arcomano © Fototeca ENIT

Basilica Palladiana in Vicenza

What: Andrea Palladio is probably modern history's most influential architect. With him, the revival of classicism reached its apogee. Doric columns, pediments, and classical arches returned to fashion in Italy, and Grand Tourists like Inigo Jones took the ideas of Palladio's "Four Books of Architecture" back to Britain. Without Palladio, the Capitol, St. Paul's Cathedral, and most of the great Western civic buildings that followed them wouldn't look anything like they do. Palladio's best work is to be found in and around Vicenza, with the Basilica Palladiana among the finest examples of his geometric proportioning.

Where: Piazza dei Signori, in Vicenza (www.vicenzae.org), about 45 miles west of Venice.

How: Vicenza also suffered during the German retreat from the peninsula in 1944-45. This compact city crammed with Palladian buildings was especially badly hit on March 18, 1945, when a targeting error rained bombs down on its historic center. The Basilica's roof was completely destroyed by a fire that nearly caused complete structural collapse. Palladio's masterpiece was renovated in 2011.

Photo Caption: Basilica Palladiana in Vicenza, Italy.

Courtesy Vicenza è tourist board

Where: Piazza dei Signori, in Vicenza (www.vicenzae.org), about 45 miles west of Venice.

How: Vicenza also suffered during the German retreat from the peninsula in 1944-45. This compact city crammed with Palladian buildings was especially badly hit on March 18, 1945, when a targeting error rained bombs down on its historic center. The Basilica's roof was completely destroyed by a fire that nearly caused complete structural collapse. Palladio's masterpiece was renovated in 2011.

Photo Caption: Basilica Palladiana in Vicenza, Italy.

Courtesy Vicenza è tourist board

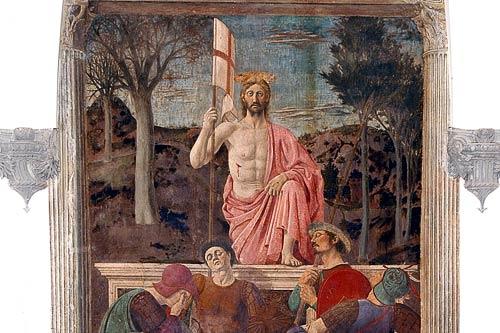

"Resurrection" at Sansepolcro's Museo Civico

What: In an essay published in the 1920s, writer Aldous Huxley judged Piero Della Francesca's 1463 "Resurrection" to be the finest artwork ever painted. Although the mysterious Tuscan is better known today for a monumental "Legend of the True Cross" fresco cycle in Arezzo, the dawn portrait of a dead-eyed, rampant Christ and four sleeping soldiers remains an icon of the early Renaissance.

Where: Sansepolcro's Museo Civico (tel. 0575-732218; www.museocivicosansepolcro.it).

How: Fast forward to 1944 and with the German Army beating a fighting retreat north through Italy, the frontline had moved to the hills above Sansepolcro. Shelling of the town had already begun when the British officer in charge, Captain Anthony Clarke, remembered reading Huxley's essay, called "The Greatest Picture," and ordered the bombardment to cease lest the masterpiece come to harm. "Resurrection" was saved, along with civilian lives; it turned out the Germans had already left.

Photo Caption: Detail of Piero Della Francesca's "Resurrection."

Courtesy Museo Civico di Sansepolcro

Where: Sansepolcro's Museo Civico (tel. 0575-732218; www.museocivicosansepolcro.it).

How: Fast forward to 1944 and with the German Army beating a fighting retreat north through Italy, the frontline had moved to the hills above Sansepolcro. Shelling of the town had already begun when the British officer in charge, Captain Anthony Clarke, remembered reading Huxley's essay, called "The Greatest Picture," and ordered the bombardment to cease lest the masterpiece come to harm. "Resurrection" was saved, along with civilian lives; it turned out the Germans had already left.

Photo Caption: Detail of Piero Della Francesca's "Resurrection."

Courtesy Museo Civico di Sansepolcro

Temples of Paestum

What: Poseidonia, later Romanized to Paestum, was one of the most important Greek cities on the Italian peninsula. Each of the three hulking Doric temples dedicated to Hera, Neptune and Ceres displays the hallmarks of fine classical architecture, all dating to around 500 BC.

Where: 23 miles south of Salerno, in Campania (tel. 0828-811023; www.infopaestum.it).

How: Engineers in the employ of Charles III of Spain (also known as the King of Naples and Sicily) were building a road from Salerno to Agropoli when they stumbled on the giant ruined temples immersed in thick forest. With scant reverence for the past, they carried on blasting a path for their road, which bisects the site to this day. History can credit them with both the rediscovery and near-despoliation of an archaeological treasure.

Photo Caption: One of the three temples of Paestum.

Photo by michael/Frommers.com Community

Where: 23 miles south of Salerno, in Campania (tel. 0828-811023; www.infopaestum.it).

How: Engineers in the employ of Charles III of Spain (also known as the King of Naples and Sicily) were building a road from Salerno to Agropoli when they stumbled on the giant ruined temples immersed in thick forest. With scant reverence for the past, they carried on blasting a path for their road, which bisects the site to this day. History can credit them with both the rediscovery and near-despoliation of an archaeological treasure.

Photo Caption: One of the three temples of Paestum.

Photo by michael/Frommers.com Community