I am a traveler. Travel is my coping mechanism. For many years, whenever the topic of suicide has come up in casual conversations, I have always proclaimed, perhaps sometimes with an inappropriate touch of cocktail party flippancy, that I could never be tempted to kill myself as long as I still have a passport and a backpack.

Out there in the world, there are empty beaches, silent forests, and teeming cities that won’t give my petty personal problems a second’s worth of indulgence. So as long as I can get a plane ticket, I liked to say, I'd never want to end it all.

After travel icon Anthony Bourdain killed himself in 2018 while in France to film another of his esteemed TV programs, I wasn't so confident about the healing properties of travel anymore.

His death was profoundly shocking, but not only to me. I have met many people who feel the same way, particularly among travelers and those who work in the food industry who still sanctify the places he went. Every so often, there's a celebrity death that is so disturbing that you're never quite ready to fully process or articulate why it rocked you: River Phoenix, Lady Diana, and Chadwick Boseman all had that effect on their respective times.

Bourdain epitomized the joys of travel for millions of people. He seemed to understand and celebrate the simple pleasures of exploration better than anyone in our culture. He surged with inspiring fortitude—here was a guy who, despite his hard-bitten cynicism, was brimming with optimism. He could venture into the most desperately poor Colombian neighborhoods to find the perfect calentao or buy out a street vendor in chaotic post-earthquake Haiti to feed local kids. He had the unfailing bravery to find love at the end of a spoon in the world's unluckiest corners.

Yet his eloquent celebrations of the things that bind us together couldn't make him want to stay alive.

Although I interviewed Bourdain myself in 2011, I haven't been able to watch one of his programs or read one his books ever since he died.

The dissonance was too existential. What if travel isn't enough?

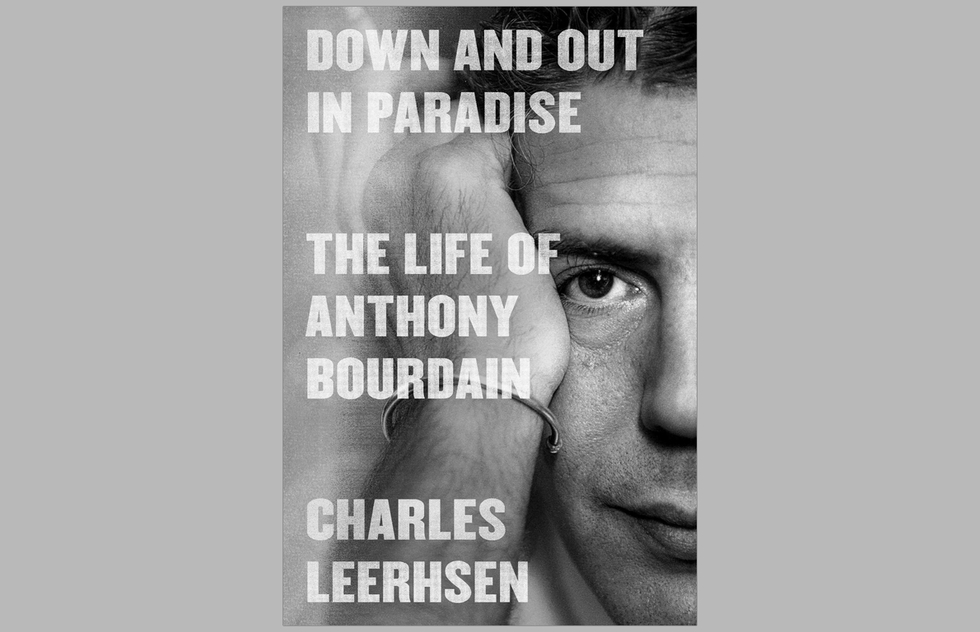

A new book, Down and Out in Paradise: The Life of Anthony Bourdain (Simon & Schuster, 320 pages, $29) might as well be subtitled The Death of Anthony Bourdain, because its chief aim is to puzzle out the reasons why a man who so confidently hit upon the secrets of life could possibly want to give it up.

Author Charles Leerhsen is a stylish and light writer who, even if he lacks the full approval of many of Bourdain’s survivors (although some 80 intimates supplied interviews, files, and most crucially, text messages), at least chooses his narrative emblems well.

To give you a sense of the tone, and of the occasionally macho assumptions that Leerhsen leans on, the book opens with a quoted passage recounting Frank Sinatra’s self-destructive passion for Ava Gardner. "He had the best job (if you could call it that) in the world... So the question is, how did he get to the point where he wanted to kill himself?" Leerhsen's early purple prose foreshadows a theory that Bourdain's fatal collapse would be like a film noir special: a crack-up over a dame.

"It all came down to the woman," the early passage opines. And to assemble the evidence, Leerhsen traces Bourdain's turbulent rise to fame and difficulties navigating it.

Tributes to Bourdain at Les Halles in New York City after his 2018 suicide (Shutterstock / Donald Bowers Photography)

Bourdain's formative struggles with heavy drug addiction are already well-known because he wrote about them himself in his breakout best-seller Kitchen Confidential (2000). In fact, his apparent success at overcoming them became an instant part of his ethos, lending gravitas to his grizzled outlook and suggesting that his fearlessness was something he'd earned from the tips of needles.

Piece by piece, Leerhsen paints a picture of man who traded the insulated world of drug addiction for the a similarly insulated universe of success and adulation.

As the vignettes mount like a string of missed red flags, it becomes much clearer that, in fact, Bourdain never left his addictions fully behind. He merely traded one set of fixations for another, and his parties transferred from after-hours comedowns with restaurant staff to between-takes hangs with whatever film crews were handy.

Like another influential and morally unsparing American writer who loved the road, Ernest Hemingway, it seems that Anthony Bourdain was often operating through alcohol. Very few travel writers have come close to their adept and trenchant turns of phrase and their genius for explaining humanity through the mundane, and like Hemingway, Bourdain seemed best equipped to use those gifts when under the influence of chemicals or self-destructive emotions.

A few high-achieving target women enter his world and spin off again like satellites, just as they typically do in the retelling of Hemingway's own downward slide. Don't blame the ladies, though; they were imperfect, but mostly bystanders to a long meltdown. Down and Out's chronicle of impending oblivion adds up to a character study of a man who never learned how to regulate his darkest feelings.

As one might expect, Leerhsen's narrative doesn't neglect abusive producer Harvey Weinstein and one of his most forceful accusers, Italian actress Asia Argento. Bourdain met her during the filming of a Rome-based episode of Parts Unknown and fell desperately in love, but she seemed to have emotional engagement issues of her own that made her a poor match.

The anecdotes about Bourdain's strained relationships contribute some low gossip and high drama, forming a page-by-page rundown of a life careering toward its dreaded final destination. Ultimately, though, Down and Out in Paradise is a story not of ill-fated romance but of permissible addiction and of immoderate living.

And also of depression and disconnection, which people around Bourdain seemed to let pass because they lived in awe of his gifts and in fear of his moods. The book lays out a slow collapse: As his success intensified, so did his removal from well-regulated emotions and from people who might have helped.

Bourdain, it's explained, tended to generate his best work during semi-manic "whoosh" periods of intense creation. He became afraid or unwilling to answer the door or phone. And he isolated. All of these are potential signs of mental illness. Being celebrated in every room you enter can be a prison because once you become famous, no room can provide true respite except an empty one.

Bourdain's addictive tendencies were already present, of course; his success on TV just required them to be channeled in more outwardly respectable ways. Those obsessive urges were merely redirected, not vanquished. And over time, as production and obligations turned his travels into a grind, he became more disconnected and increasingly preoccupied by an unhealthy relationship with Argento.

Leerhsen obtains Bourdain's Google history for the last few days before his death, and it shows he searched for Asia Argento "several hundred times" in his hotel room.

Author Charles Leerhsen (Photo: Steve Hoffman)

For the record, Leerhsen concludes Bourdain's exit was intentional and by his own hand. The book explicitly dismisses the persistent rumor that Bourdain's death was the accidental result of autoerotic asphyxiation—he had been clothed. Instead, a bit distastefully, Leerhsen leans into his gumshoe narrator voice and calls the suicide method "the preferred celebrity style" by pointing out its similarities to the death scenes of Robin Williams and Kate Spade.

Bourdain's final act may have amounted to a rash decision by an intense personality, but as Leerhsen retells it, it was fed mostly by disconnection and fixation. Not in spite of his heavy travel, but because of it, inasmuch as a schedule that cycled through strangers prevented from him from maintaining lasting and meaningful outlets for healthy emotions. As Bourdain's success multiplied, so did his old tendencies to seek mental escape.

Ultimately, the story of Bourdain, who was assumed by so many to be a master traveler, becomes a tale of how to travel poorly.

But at a certain point, as Leerhsen explains, the traveler with a gift for finding life-affirming joys of the road began to see an abyss in them instead. He couldn't leave his obsessions at home.

Turning the final page (and reading the excellent explanatory endnotes that explain how the best scoops were attained), I finally felt like I got the answers I needed from Down and Out in Paradise.

For Anthony Bourdain, travel was not enough.

And travel never will be enough if we cannot maintain fundamental mental health.