5 Things You Don't Know About Yucatan's Mundo Maya

By

Merida, Chichen-Itza and the Mayan Interior

The ochre-colored convent of San Antonio de Padua, in Izamal.

The Other Yucatan: Mayan Ruins & More

By Christine Delsol

For a generation of tourists, "the Yucatán" has come to mean Cancún and the Riviera Maya -- an area bearing little resemblance to the Yucatán that drew the first travelers to Mexico's mysterious southern peninsula after New York writer John Lloyd Stephens and illustrator Frederick Catherwood recounted their mid-19th century explorations of a "lost civilization" in the jungle. But with this slideshow, we'd like to turn the attention back to the Yucatán's still very much present Mundo Maya.

Photo caption: El Castillo, Chichén Itzá

For a generation of tourists, "the Yucatán" has come to mean Cancún and the Riviera Maya -- an area bearing little resemblance to the Yucatán that drew the first travelers to Mexico's mysterious southern peninsula after New York writer John Lloyd Stephens and illustrator Frederick Catherwood recounted their mid-19th century explorations of a "lost civilization" in the jungle. But with this slideshow, we'd like to turn the attention back to the Yucatán's still very much present Mundo Maya.

Photo caption: El Castillo, Chichén Itzá

Valladolid, Mexico

Cenote X'keken in Valladolid.

2012 ended up not being the end of the world (and it wasn't even the end of the Maya calendar)

It was the flipping of a page, numerically significant but in no way apocalyptic. The Long Count calendar is a complex mathematical creation that the Maya have not used since the Classic Maya period (250-900 A.D.). The end of one 5,125-year "long cycle," made up of 13 bak'tuns (about 394 years), coincided with December 2012. The exact date was a matter of debate, but Dec. 21 had the edge because it coincided with the solstice. The ancient Maya assumed an earlier long cycle ended before their tenure on earth—unblemished, notably, by any sort of mass destruction—and surviving inscriptions refer to future events to come in the next long cycle. The Maya left no records foretelling any sort of cataclysm accompanying the turn of the 13th bak'tun.

Photo caption: The ruins of a Mayan calendar in the Yucatán.

Photo caption: The ruins of a Mayan calendar in the Yucatán.

Valladolid, Mexico

Mayan ruins at Ek Balam, Oval Palace.

Only a few vague references to 2012 exist in surviving Maya texts.

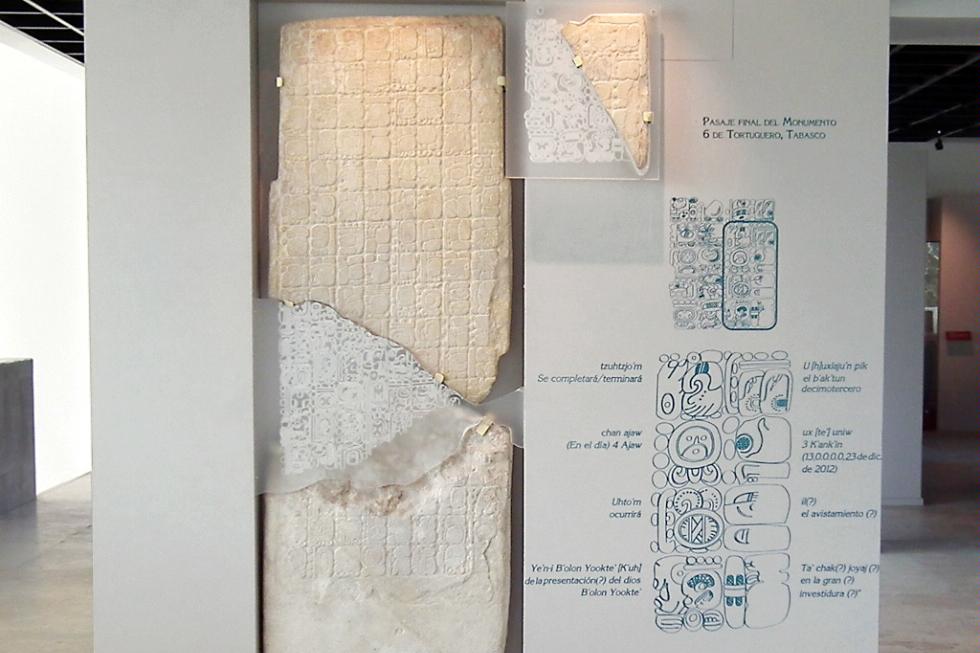

The end-of-the-world fantasies we heard so much about back in 2012 were built on a single stone fragment from the state of Tabasco. Monument 6, as it is known, was rescued from the tiny ruin of El Tortuguero, which had been heavily damaged and looted before it was buried under a cement factory in the 1960s. The inscription records the life of King Bahlam Ajaw in the early 7th century. The most recent interpretation, coming out of a roundtable of Maya scholars in December 2011, determined that the text ends with a reference to the end of the 13th bak'tun, when Bahlam Ajaw would host of Bolon Yokte', a deity who would descend for the transition to a new calendar cycle -- as he had at the beginning of the current era. These fragments reside in the Carlos Pellicer Regional Anthropology Museum (www.mexonline.com/villahermosa.htm) in Villahermosa. Two other references to 2012 have surfaced since then: the "Comalco Brick" fragment uncovered at the nearby Comalco ruin, and a stone uncovered at La Corona in Guatemala's Petén district to commemorate a visit from the king of Calakmul, the most powerful Maya city of the time. Neither contain prophecies of doom, and neither are on public display.

Photo caption: Monument 6 from the ruin of Tortuguero at the Museo Regional de Antropología Carlos Pellicer Cámara in Villahermosa, México.

Photo caption: Monument 6 from the ruin of Tortuguero at the Museo Regional de Antropología Carlos Pellicer Cámara in Villahermosa, México.

Merida, Chichen-Itza and the Mayan Interior

The ruins of Mayapan.

Chichén Itzá ain't what it used to be

The walls' brightly painted stucco coating, the common people's homes in surrounding jungle clearings, and the bustle of commerce, ball games, and wars are missing, of course, but that's only half the story. Chichén Itzá's consecration as a "New World Wonder" has made the magnificent city harder to appreciate. Seeing plastic El Castillo key chains and night lights in every souvenir shop and standing in line to get an unobstructed photo of the pyramid eats into the awe factor, and long gone are the days when you could scale El Castillo. Best bet: Spend a night nearby and visit the ruins early, before the tour buses roll in. (You can come for the evening light show and use the same ticket in the morning.) If the hotels at the gate are beyond your budget, try the Hotel Dolores Alba down the road. Even better, make your base in the picturesque and historic town of Izamal or the seriously underrated colonial city of Valladolid, which are a short hop from Chichén Itzá and offer ample opportunity to mingle with local Maya people, explore remote cenotes and haciendas, and discover some of the lesser-known ruins for yourself.

Coba Ruins

Visitors climb the Coba ruins.

Some of the best Maya ruins are the least-visited.

Though Chichén Itzá is the world's most famous Maya site, archaeologically it is more notable for its strong Toltec influence. Many better places to delve into the architecture, style and daily life of the Maya remain lightly visited. The ceremonial complex of Uxmal, the nearest large site to Chichén Itzá, is a Maya masterwork, unique for its intricately carved stone facades, its varying elevations, and lack of any suggestion of military ambition. At Ek Balam, you can scale the 100-foot El Torre (or Acropolis) pyramid, which easily surpasses Chichén Itza's El Castillo, and the elaborate, miraculously well-preserved stucco friezes covering three-fourths of the Templo de los Frisos will leave you gape-jawed. Small and out-of-the-way Mayapán, last of the great Maya city-states, contains the full spectrum from jungle-covered mounds to fully restored structures -- including the temple of Kukulcán, a smaller version of El Castillo, with its vivid red and orange murals. Archaeologists consider Campeche's Edzná one of the most significant Maya ruins, yet it gets fewer visitors in a year than Chichén Itzá does in a day. The elegant architecture reveals the city's significance as a crossroads, employing roof combs and corbeled arches similar those of Palenque and giant stone masks characteristic of the Petén style made famous by Tikal in Guatemala. These and many smaller cities, such as the ruins along the Pu'uc route, are still infused with a quiet, ancient spirit.

Photo caption: The ruins of Mayapan.

Photo caption: The ruins of Mayapan.

Uxmal

The Governor's Palace ruins in Uxmal.

The Maya civilization is not "lost."

The Maya ferociously resisted the Spanish for decades after the rest of Mexico capitulated -- even today, they are Maya first and Mexicans second, if at all -- and remain one of the most pure-blooded indigenous groups in the country. They have preserved their traditions while adapting to contemporary life with uncommon grace and dignity, and any Mundo Maya journey should also aim to discover the rich Maya culture of today. Mérida is a modern metropolis where huipiles embroidered in neon colors mingle effortlessly with jeans-clad, iPhone-toting kids and adults dressed for business on city sidewalks. Maya people from outlying villages stream in to Valladolid daily to sell indigenous clothing and crafts. In Izamal, where a massive pyramid rises in the middle of town, you can visit dozens of workshops that produce art and merchandise by methods passed down through the centuries. Even on the Riviera Maya, where most of the traditional culture is packaged for tourist consumption, you can also visit the Maya village of Pac Chen near Cobá, where time seems to have stopped, and Puerto Morelos' Jungle Spa cooperative for a treatment from Maya women who learned traditional healing massage with their ABCs. In the Yucatán, you don't have to venture far beyond your comfort zone to realize that this is not a lost civilization, but a very much alive and continually evolving one.

Photo caption: A Mayan mother living in a traditional Mayan village.

Photo caption: A Mayan mother living in a traditional Mayan village.

Uxmal

The Pyramid of the Magician, Uxmal Mayan ruins.

Merida, Mexico

Merida's busy Plaza Grande.

Merida, Chichen-Itza and the Mayan Interior

Mayan ruins at Mayapan.

Uxmal

Detail on exterior of Nunnery Quadrangle, Mayan ruins of Uxmal.