Vintage Postcards of Tourist Attractions: The Same View Then and Now

By Jason Cochran

Some people travel for conquest. Some people travel for food. Me, I travel for history. Each new destination I visit opens another timeline of things to learn, and I, like many travelers, will go out of my way to lay eyes on locations where something important happened—just to see how things have changed.

It's for travelers like me that the ScenePast smartphone apps were compiled—they conjure before-and-after images of major landmarks and panoramas that you can toggle between wherever you go and really dig into what time has done to your destination. Its researchers came up with a selection of popular tourism locales to show how the years have changed some of the United States' most treasured tourism sights.

Click on through and compare but do it soon, because pretty soon, even the "today" images will be in the past.

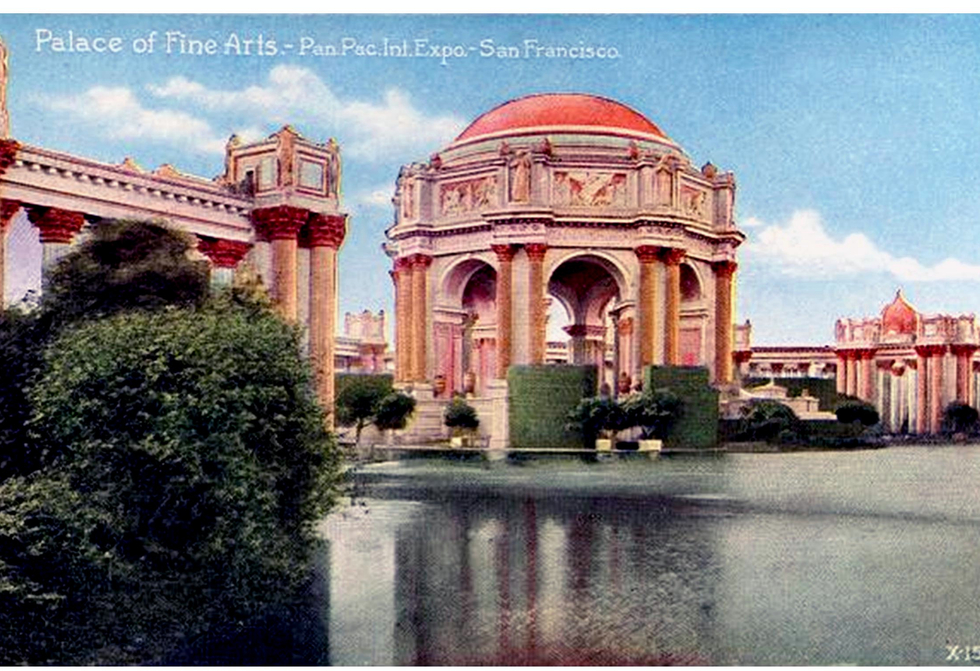

Image: The Palace of Fine Arts, 3301 Lyon Street, San Francisco, in a 1915 postcard.

It's for travelers like me that the ScenePast smartphone apps were compiled—they conjure before-and-after images of major landmarks and panoramas that you can toggle between wherever you go and really dig into what time has done to your destination. Its researchers came up with a selection of popular tourism locales to show how the years have changed some of the United States' most treasured tourism sights.

Click on through and compare but do it soon, because pretty soon, even the "today" images will be in the past.

Image: The Palace of Fine Arts, 3301 Lyon Street, San Francisco, in a 1915 postcard.

The Palace of Fine Arts, San Francisco, today

As it turns out, the Palace of Fine Arts is supposed to look a little ruined, as its designer was inspired by an etching of Roman ruins. It was also built on ruins. Erected for the Pan-Pacific Exposition of 1915, it stands on acres of land that was reclaimed using rubble from the horrified quake and fire of 1906. The ruins of San Francisco slumber beneath it. The architect said at the time that his work was about “the mortality of grandeur and the vanity of human wishes"—quite an ironic thing to build on top of the mess left by a horrific disaster. Most of the other Exposition buildings are distant memories, but this intentionally open-air structure, perhaps ironically, this ruin-on-ruins is the longest-lived element from the campus. The topiaries are gone, but it remains a very pretty place, and it's still a popular hangout and theatre.

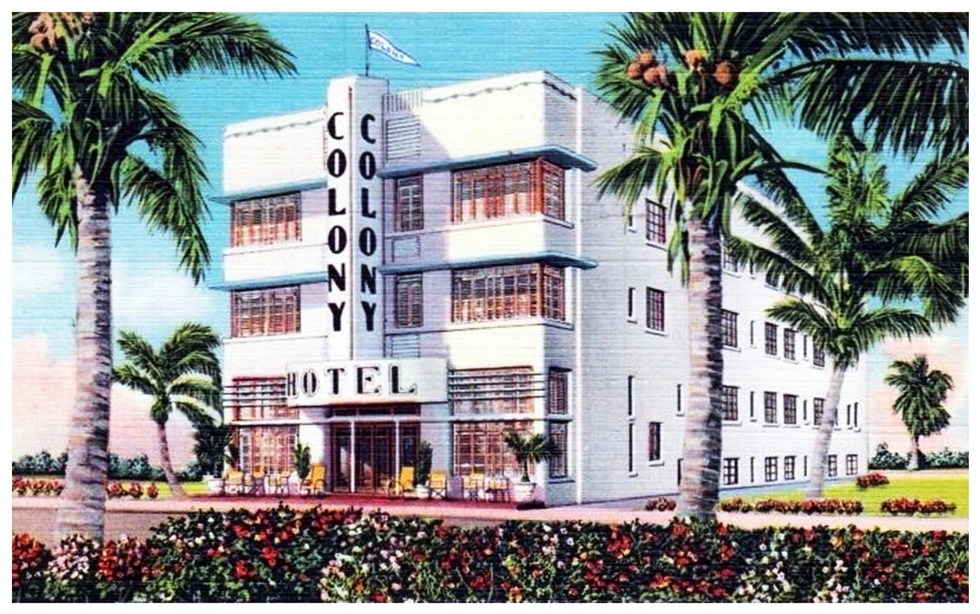

Colony Hotel, 736 Ocean Dr., Miami Beach (1930s)

This postcard was issued to brag about the 1935 opening of one the first hotels to give Miami Beach its worldwide reputation for Art Deco. Miami Beach's future was by no means certain at the time. A hurricane all but obliterated the fledgling area in 1926, so the beach town's rebirth had to be brassy if people were ever going to want to move back there. The city fathers thought Art Deco might be the thing to put it back on them map.

Colony Hotel Miami Beach (today)

Fortunately, the Colony survived, and in time it became the most famous Art Deco hotel in a city famous for Art Deco. its owners have wisely renovated it with a deep respect for its stylistic intent. It even looks a little more inviting today than it did back in the day, and best of all, it's still possible to get a room here for less than $100 (read our review of the Colony Hotel here). Times haven't changed that much in Miami Beach—the Colony is still the star of the postcard racks today.

Tomorrowland entrance, Disneyland, Anaheim, California (1960s)

The rudiments of Tomorrowland opened along with Disneyland in July of 1955, but the area would end up changing more than any other part of the park. Major renovations came in 1967 and again in 1998. The ride in the background is Rocket Jets, which operated from 1967 until 1997; its sister ride is still flying in the Orlando park.

Tomorrowland entrance, Disneyland, Anaheim, California (today)

Successive rehabs of Tomorrowland have largely removed futurism from the design—as it turns out, the future dates pretty badly—and replaced it with a pseudo-steampunk/Jules Verne look as epitomized by the Astro Orbitor ride, which appeared in this entrance location in 1998. It looks funky and it's in a new spot, but it's essentially a version of the old Rocket Jets ride.

Las Vegas Club, Fremont Street & Main Street, Las Vegas (1970s)

Now this is Vegas, baby: Loud neon! Way too many light bulbs! You can almost hear the ice clink in Dean Martin's highball glass and see the sparkles fly off Elvis' Nudie suit. Seen here in the 1970s, the Las Vegas Club was a stalwart of Downtown Las Vegas—back in 1931 it was even the first Vegas casino to install a neon sign.

Las Vegas Club, Fremont Street & Main Street, Las Vegas (2014)

As with much of Vegas, this corner has a design that's now less like the Rat Pack and more like a mobster's guest bathroom. The louvered canopied roof of the Fremont Street Experience (on the right) opened in 1995. By early 2015, the hotel, restaurants, and parking garage connected to the Las Vegas Club had all closed—only the casino jangled on, awaiting the next major transformation.

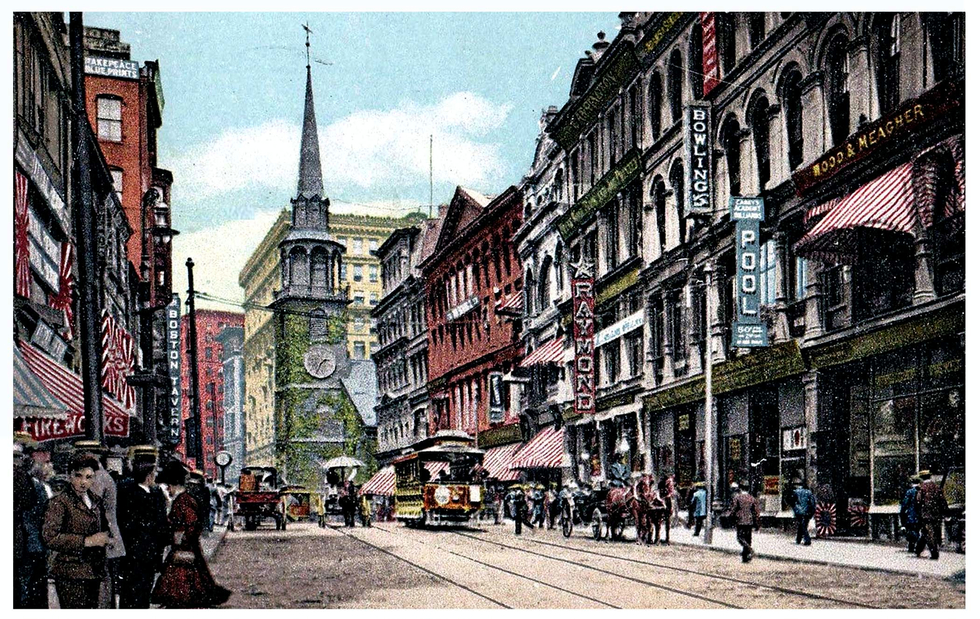

Old South Meeting House, 310 Washington St., Boston (1900s)

We meet the Old South Meeting House in the early 1900s when it was already nearly two centuries old. Built in 1729, it was the largest hall in Boston in 1773, which is why some 5,000 Bostonians crammed it to debate whether they should protest the Crown by destroying property that was sitting in British ships. That laborious and nail-biting debate resulted in what is now remembered as the considerably more lively and spontaenous Boston Tea Party. The church nearly burned down in the Great Fire of 1872, so by the time this photograph was taken, the treasured building was already quite, um, revered.

Old South Meeting House, 310 Washington St., Boston (today)

There is no law against opening a T.J. Maxx near a national treasure, so today the Old South Meeting House is so hemmed in with dull modern buildings that a casual passerby might be lulled into forgetting its importance in American history. Since many of Boston's residents moved to the suburbs, the street life is a lot less thrilling today, but inside the House, you can still see a vial of tea from the 1773 uprising, and each December, it organizes a family-friendly re-enactment—odd, when you consider it was pretty much an act of terroristic vandalism. (Read Frommer's' listing of the Old South Meeting House here.)

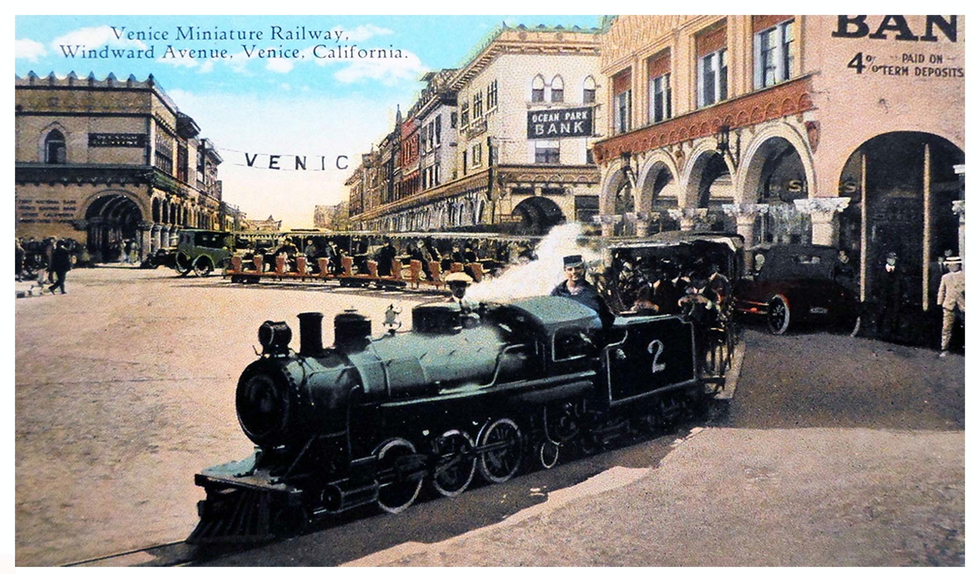

Venice Beach Miniature Railway, Pacifica and Windward Avenues, Venice, California (1910s)

Here's a novel way to sell real estate: Venice founder Abbot Kinney built this 2 and 1/2-mile-long miniature railway in 1905 to show prospective buyers around the streets and canals of his development, Venice, which was built to emulate the canals and aesthetics of the Italian city-state. As the presence of a miniature train might suggest, the depiction was less than faithful, and Venice was soon known as "Coney Island of the Pacific," with pleasure-seekers whisked from Los Angeles' business district by streetcar. This postcard was issued by Western Publishing & Novelty Co. Movie star Harold Lloyd rode the rail road in his films By the Sad Sea Waves and Number Please?.

Venice Beach Miniature Railway, Pacifica and Windward Avenues, Venice, California (today)

The rail road became a victim of its own success. So many people flocked to Venice in automobiles that in 1925, the route was deemed a danger and it was scrapped. Most of the town's original canals were also filled in and became roads by World War Two. The Ocean Park Bank building, too, was shaved to one floor and now contains a smoothie place. This, some say, is progress.

Fremont Hotel, 200 Fremont St., Las Vegas (1960s)

Liberace is playing the Sky Room! I think that even before we see the "now" slide, we can agree that this view is better.

At the time this was taken, it was the tallest building in Nevada, having been built for $6 million—a bargain for a new casino by Las Vegas standards, even adjusted for inflation. The Sky Room was a saucer-shaped lounge on the roof of a mid-'60s addition, while the main headliner space was the Carnival Lounge. Only a few years before, a Shell station stood on this spot, but in 1959, a teen-aged Wayne Newton made his Las Vegas debut here. He was so young he had to be escorted out of the casino after he finished his act.

At the time this was taken, it was the tallest building in Nevada, having been built for $6 million—a bargain for a new casino by Las Vegas standards, even adjusted for inflation. The Sky Room was a saucer-shaped lounge on the roof of a mid-'60s addition, while the main headliner space was the Carnival Lounge. Only a few years before, a Shell station stood on this spot, but in 1959, a teen-aged Wayne Newton made his Las Vegas debut here. He was so young he had to be escorted out of the casino after he finished his act.

Fremont Hotel, 200 Fremont St., Las Vegas (today)

For all its innovatinos, now the vaunted Fremont doesn't even have its own pool (you have to cross the street to use the one at the California Hotel), but it's still open, and it now opens up into the 90-foot-high light show of the Fremont Street Experience attraction. From Liberace to Dunkin' Donuts: So has gone mainstream American culture. The main vitality of luxury Las Vegas moved from the business district to the Strip, and now the old Fremont Hotel, though retaining its eyelid windowshades, has smudged its mascara. But at around $50 a night, it's a cheap way to get a little history into your Vegas diet.

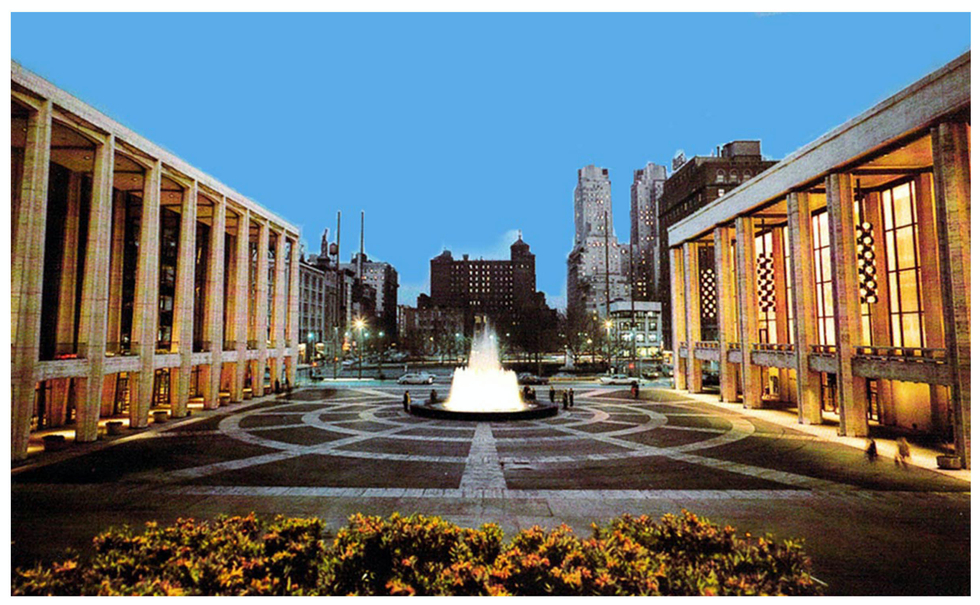

Lincoln Center, 10 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York City (1960s)

This is a "before" shot, but if you want to see before "before," just watch West Side Story—the movie was shot in a neighbhood slated for demolition to make way for the Lincoln Center arts and entertainment district. (At times, wrecking balls were knocking down buildings directly behind director Robert Wise's camera.) But this view is of the finished showplace from the perspective of the entrance of the Metropolitian Opera House. Avery Fisher Hall is to the left and the New York State Theater is to the right. Straight ahead is Broadway and over those buildings is Central Park.

Lincoln Center, 10 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York City (today)

Most heritage buildings were swept away in the land boom after Lincoln Center proved itself, so you'll no longer find any of the grittiness that convinced midcentury New Yorkers that the neighborhood required redevelopment. The only gangs at Lincoln Center are now dancing on stage in revivals of West Side Story. The New York State Theater was renamed the David H. Koch Theater for the coal-and-oil baron and aggressive libertarian whose donation purchased naming rights, and in 2014, the Avery Fisher's name went for sale for the highest bidder, too. You guessed it: Lincoln Center is now where the wealthy dwell and amuse themselves. The tall building in the middle, across the street on Broadway, houses the headquarters of Sesame Workshop, the non-profit company that steers the Sesame Street brand, and the performance rights organization ASCAP.

Fisherman's Wharf, Jefferson and Taylor streets, San Francisco (1920s)

Located at the top end of San Francisco near North Beach, the Fisherman's Wharf area was settled by Italian immigrants and fishermen. As you can see, even then it was a little touristy. Those dames aren't there to fish.

Fisherman's Wharf, Jefferson and Taylor streets, San Francisco (today)

The Wharf, diminished since its heyday, is still a working fish market, and crab haulers still come in at Pier 45, in the center background—but it's now so touristy that locals tend to avoid it. Ironcially, Pier 45 contains is now known for containing some 200 coin-operated games and amusements that were manufactured around the time the previous image was taken; that's where you'll find the one-of-a-kind arcade Musée Mecanique.

Franciscan Restaurant, Pier 43 1/2, Fisherman's Wharf, San Francisco (1950s)

Turn a little right from the previous view and you'll see the Franciscan Crab Restaurant, built in that glassy ranch style that's so prevelant in California. In the mid-1950s, when it opened, this was the latest word in architecture.

Franciscan Crab Restaurant, Pier 43 1/2, Fisherman's Wharf, San Francisco (today)

In 1996, the owners poured $3 million into a renovation, and in case tourists didn't realize that this "crab restaurant" at Fisherman's Wharf served seafood, they tarted up those clean midcentury lines to make it look like a ship, portholes and all. Subtlety is not its forte—longevity is, and it remains a fixture of the area.

Old Absinthe House, 234 Bourbon Street, New Orleans (1910s)

A century ago, when this was taken, this French Quarter building was already more than 100 years old and it was famous for ladling its namesake spirit. Oscar Wilde, Andrew Jackson, Mark Twain, and Walt Whitman are all said to have partaken of "The Green Fairy" here.

Old Absinthe House, 234 Bourbon Street, New Orleans (1910s)

The Old Absinthe House is looking a little better for the wear, perhaps because absinthe, which causes blindness and madness, has been banned in the form in which it was served in the previous shot. The owners, no longer spackled on drink, maintain the building a little better—and it helps that it's such a touristic icon of the Big Easy. Look: There's even an Ignatius-style hot dog stand in front of it. The grit may be for show now, but the heritage of the Old Absinthe House (read Frommer's' listing here) is the real deal. Unsurprisingly, it's thought to be haunted.

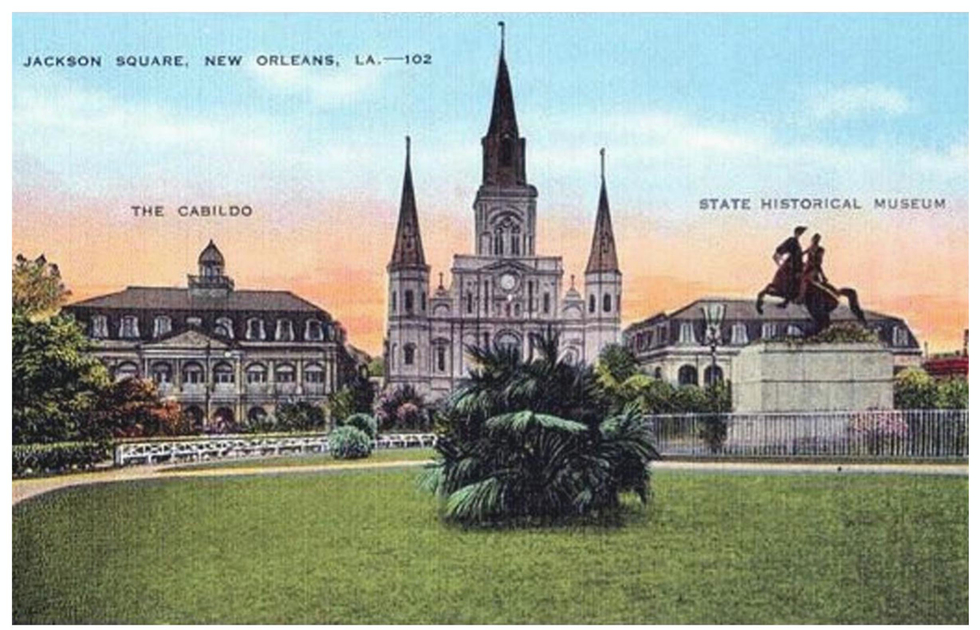

Jackson Square, Decatur Street, New Orleans (1930)

New Orleans' preeminent public space, Place d'Armes, was renamed for a pre-presidential Andrew Jackson after he helped repel the British from New Orleans in 1815. That's his statue on the right.

Jackson Square, Decatur Street, New Orleans (today)

Thank goodness—a view that is unchanged!

Or so it seems. In fact, the cupola and top floor of the Cabildo, on the left, were destroyed in a 1988 fire; what you see now is a faithful reconstruction. All the streets in view were pedestrianized a generation ago, making it an even more popular promenade spot. The building on the right is now The Presbytère. St. Louis Cathedral, at the center, was visited by the Pope in 1987. And the statue of Andrew Jackson is obscured by a tree, which given modern perspectives of his mores gives some scholars relef.

Or so it seems. In fact, the cupola and top floor of the Cabildo, on the left, were destroyed in a 1988 fire; what you see now is a faithful reconstruction. All the streets in view were pedestrianized a generation ago, making it an even more popular promenade spot. The building on the right is now The Presbytère. St. Louis Cathedral, at the center, was visited by the Pope in 1987. And the statue of Andrew Jackson is obscured by a tree, which given modern perspectives of his mores gives some scholars relef.