Exploring the Best Artifacts from the National African American Museum

By Candyce H. Stapen

Long-planned and anticipated, the new, $540 million Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) explores the rich saga of African American history and life in the United States. In a new building beside the Washington Monument and near the White House—which, like so much of our early nation, was built using slave labor—nearly 4,000 artifacts in 12 galleries document slavery, segregation, and the Civil Rights Movement. The collection doesn't only focus on social struggle, though. It also traces Black contributions to sports, music, art, dance, theater, television, film, and the military.

The building’s three-tiered, bronze-colored corona is inspired by the Yoruban caryatid, a traditional column topped with a crown. Piercings in the panels, an evocation of the decorative ironwork in Charleston and New Orleans—two cities also largely built by slaves—admit light for the exhibitions. Some of the best and rarest items in U.S. history were donated for the institution's displays. Let's take a look at a few of the coolest things.

The building’s three-tiered, bronze-colored corona is inspired by the Yoruban caryatid, a traditional column topped with a crown. Piercings in the panels, an evocation of the decorative ironwork in Charleston and New Orleans—two cities also largely built by slaves—admit light for the exhibitions. Some of the best and rarest items in U.S. history were donated for the institution's displays. Let's take a look at a few of the coolest things.

Middle Passage ankle shackles

Ships laden with goods once regularly sailed from Europe to the West African coast. Captains would trade cargo in exchange for captured Africans, who were packed into the hold and restrained by ankle shackles like the 1863 pair pictured above. When the hold was filled with captives, the vessel sailed across the Atlantic to the New World. Upon arriving, the surviving Africans were sold or traded for sugar, rum, molasses, or other raw materials, and the ships returned to Europe in the final leg of the trade route. This torturous abduction of Africans became known as the “Middle Passage,” or the second leg of that demented triangular trade route in which people were considered no more than goods to be traded. These shackles were for a child.

Slave cabin

This weatherboard cabin dating to the early 1800s once housed slaves at the Point of Palms Plantation on Edisto Island, South Carolina. The plantation, established in 1674, occupied 1,000 acres, and at one time, the estate kept 170 slaves and 25 slave cabins. The cabin, made of yellow pine and cypress, has been moved inside the museum.

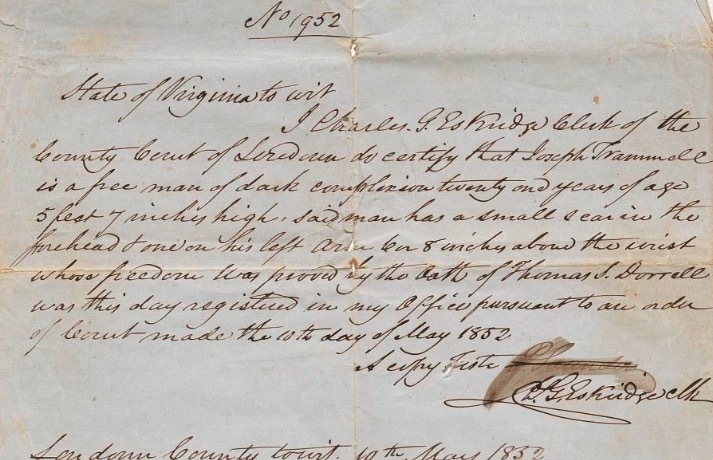

Certificate of Freedom for Joseph Trammell (detail)

On May 10, 1851, Joseph Trammell was granted his freedom from bondage. His only proof that he was a freeman, and the only thing that would prevent him from being instantly carted away in chains once again, was this piece of paper from Loudoun County, Virginia, which he kept in a tin box (also on display) for safekeeping. Trammell died in 1859, two years before the Civil War. Like some 80% of what's on display at the museum, this heirloom was donated.

Tuskegee airplane

At the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, African American men were trained as pilots by the Army Air Corps service during World War II. Their open-cockpit biplane, a Boeing-Stearman PT-13D Kaydet (circa 1944), now hangs from the ceiling in the museum.

Hat from Mae’s Millinery

Mae Reeves, one of the first black female business owners in Philadelphia, designed this blue-and-white hat with the blue tulle streamer. In the '40s and '50s, Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne, Eartha Kitt, Marian Anderson, and scores of nonfamous black women looking for the perfect Sunday church outfit shopped at Mae’s Millinery Shop, which was open from 1941 to 1994. Part of Mae’s store is simulated in "The Power of Place," an exhibit that explores place and region as part of the African American experience.

Church pew from the Twelfth Baptist Church of Boston

The gallery “Making a Way Out of No Way" depicts how African Americans created possibilities for themselves in an often hostile world. Their efforts were buttressed by education, religion, business, social organizations, and the press—all important pillars of African American life. This wood and metal church pew dates to the mid-19th century. Since the Twelfth Baptist Church of Boston’s inception in 1840, when it served as an Abolitionist meetinghouse, the church has worked to thwart the oppression of African Americans while promoting spiritual well-being.

Lunch counter stools from Greensboro, NC

On February 1, 1960, four freshmen (Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair, Jr. and David Richmond) at North Carolina A&T University sat down at a whites-only lunch counter at Greensboro’s F.W. Woolworth store and stayed until closing, waiting to have their orders taken. They were never served. The next day, and for the rest of February, more African Americans and supportive whites joined the peacful protest—as did hostile whites. Still, the success of the Greensboro sit-in inspired similar actions to desegregate motels, beaches, libraries, and public places across America. Greensboro's Woolworth’s store was desegregated on July 26, 1960, and is now a museum, which donated these seats to the Smithsonian, where they appear in a gallery chronicling segregation.

March on Washington, D.C. for Jobs and Freedom

On August 23, 1963, more than 250,000 people converged on Washington, D.C., marching from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial in support of civil rights for African Americans. At the event's climax, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech calling for the fulfillment of Constituional rights for all Americans regardless of race. The next year, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, striking down segregation in public places and requiring businesses to provide equal employment opportunities. This image is part of the museum's digital collection.

Chuck Berry’s Cadillac

The Musical Crossroads gallery celebrates African American music, from the songs of slaves to contemporary hip-hop, soul, and R&B. Artifacts include Marian Anderson’s outfit for her defiant 1939 Lincoln Memorial concert, Sammy Davis Jr.’s tap shoes, and Chuck Berry’s 1973 red Cadillac.

Chuck Berry was one of the pioneers of rock 'n' roll. His car, an emblem of success and high style in the entertainment business, was driven during the filming of Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll, Taylor Hackford's 1987 documentary that gathered together some of the greatest African American musical talents of the 1950s and '60s.

Chuck Berry was one of the pioneers of rock 'n' roll. His car, an emblem of success and high style in the entertainment business, was driven during the filming of Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll, Taylor Hackford's 1987 documentary that gathered together some of the greatest African American musical talents of the 1950s and '60s.

Louis Armstrong’s Selmer trumpet

Louis Armstrong, nicknamed Satchmo, made his trumpet come to life. The musician, who was a grandson of slaves, helped popularize jazz with his stylistic solos. Armstrong’s trumpet, circa 1930, was made by Henri Selmer of Paris.

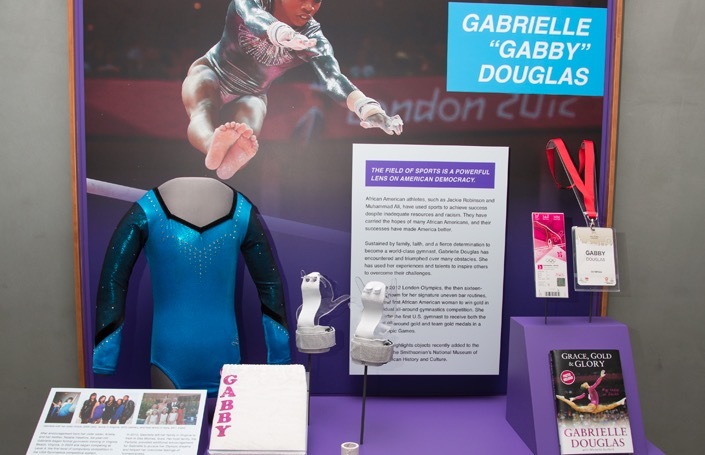

Gabby Douglas display

The Sports Gallery details how professional athletics became one of the first highly visible arenas to accept African Americans. Artifacts include Althea Gibson’s 1957 Wightman Cup blazer, Jim Brown’s signed 1965 Cleveland Browns football jersey, and Curtis Charles Flood’s 1966 St. Louis Cardinals jersey, as well as an array of items from gymnast Gabby Douglas. These include the leotard she wore in the 2004 Virginia State Championships, the uneven bar grips she used at the 2012 London Summer Games, and the credentials she used to access London Olympic venues.

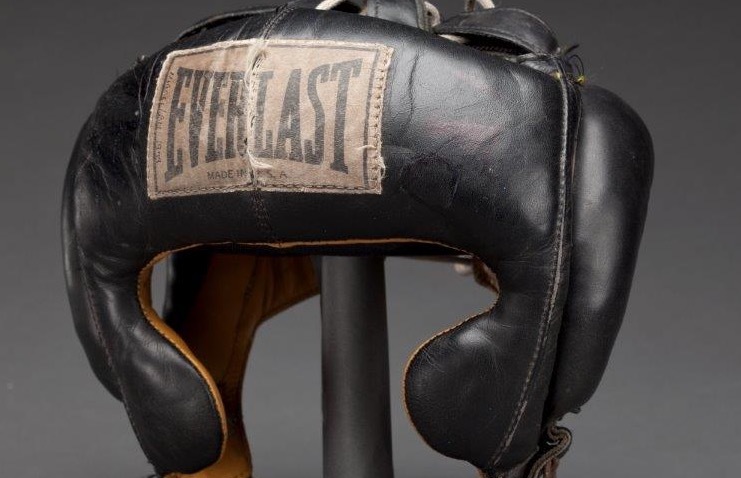

Muhammad Ali headgear

Muhammad Ali used this headgear while training with Angelo Dundee at the 5th Street Gym in Miami Beach, Florida. Today, a CVS pharmacy is on that site, but Ali's original equipment, including his gloves, is safely preserved in the Smithsonian's Sports Gallery.

Detroit Lions jacket worn by Eddie Murphy in "Beverly Hills Cop II"

The "Taking the Stage" area chronicles African American achievements in entertainment. Notable holdings include Ntozake Shange’s dress for Lady Orange in her work For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf, Lena Horne’s green velvet dress for her role in Stormy Weather, and the Detroit Lions jacket worn by Eddie Murphy in the blockbuster Beverly Hills Cop II.

Pete Souza photograph

Official White House photographer Pete Souza took this now-famous image of President Obama bowing for 5-year-old Jacob Philadelphia, who visited the Oval Office in 2009 and was fascinated to find a man with hair that was similar to his own. The picture hung on the walls of the West Wing for several years and is now part of the collection.

The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture is online at nmaahc.si.edu.

The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture is online at nmaahc.si.edu.