12 Surprising Things You'll Learn at Philadelphia's Museum of the American Revolution

By Frommer's StaffAs the Founding Fathers musical Hamilton points out, history is all about “who lives, who dies, who tells your story.” For a long time, the official story told about the American Revolution was a triumphant tale of liberty-loving patriots rising as one to overthrow the tyrannical British. In recent decades, though, that simple narrative has been made more complex by including the perspectives of groups—enslaved African Americans, women, Native Americans—denied liberty, and by acknowledging the considerable uncertainty, fear, and turmoil that goes with casting off one government and starting another.

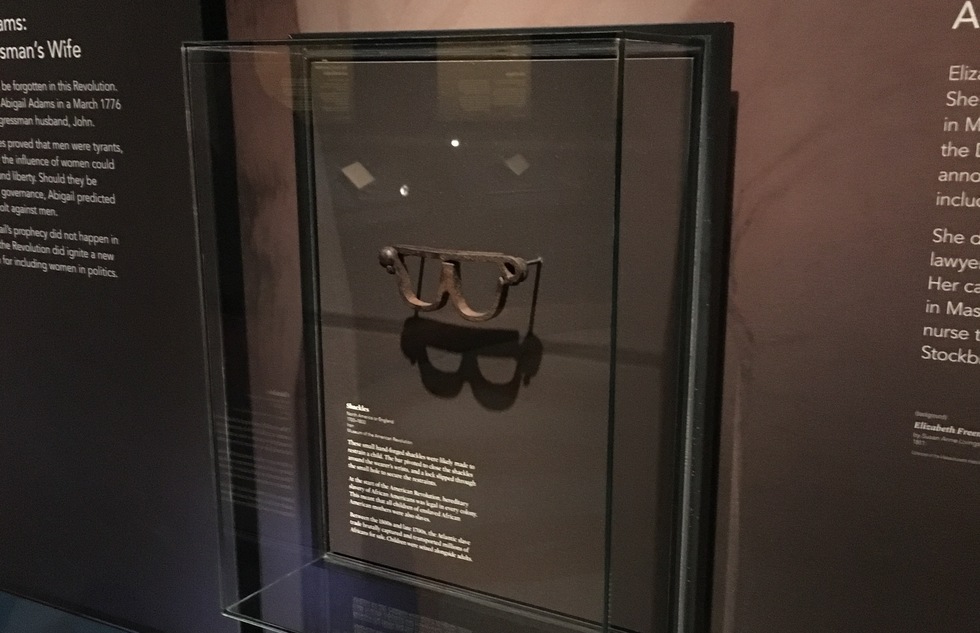

Philadelphia’s Museum of the American Revolution uses period art and artifacts—ranging from General Washington’s field tent to slave shackles designed to fit a child—as well as interactive displays, immersive tableaus, and video reenactments to convey a broad understanding of life before, during, and after the struggle for American independence. Visitors are liable to walk away from the museum knowing some stuff they weren’t taught in fourth grade. Here are 12 surprising things we learned.

Pictured above: a replica of a Liberty Tree, where colonists in several cities would gather to stage acts of defiance against the British government in the leadup to the Revolution

The Continental Congress deleted a mention of slavery from Thomas Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. But that didn’t stop many enslaved African Americans from finding an unfulfilled promise in the document’s claim that “all men are created equal”—even though the author of those words was himself a slaveholder.

In Massachusetts, an enslaved woman named Mumbet (she later changed it to Elizabeth Freeman) heard the Declaration read and announced that it applied to her, too, whereupon her master hit her with a frying pan. But she sued for her freedom and won it, establishing a precedent that led to the abolishment of slavery in her state. At the museum, an exhibit telling her story stands next to a display case containing a tiny set of slave shackles (pictured above), probably designed to restrain a child—a heartbreaking reminder of the cruelty inherent in the “peculiar institution.”

Stark divisions among Americans were in place long before the Civil War broke out in the 1860s. Fourscore and seven years or so before that conflict, Gen. George Washington knew the importance of uniting the colonists to fight the British, but even he—a wealthy Virginian—described the Yankee soldiers under his command as “an exceedingly dirty and nasty people.” Between displays of Continental Army uniforms and weapons, a tableau at the museum depicts a 1775 brawl (pictured above) in Harvard Yard near Boston. The combatants weren’t Minutemen and redcoats but New England soldiers vs. riflemen from Pennsylvania and Virginia. According to an eyewitness, it took Washington himself to break up the fight.

So-called "Hessian" soldiers were among the most feared of the troops who crossed the sea to fight. They got their name from two of the German-speaking principalities they came from (Hesse-Cassel and Hesse-Hannau), though in reality these men were drawn from six small European nations.

Pictured above: pieces of embossed brass worn on distinctive Hessian headgear

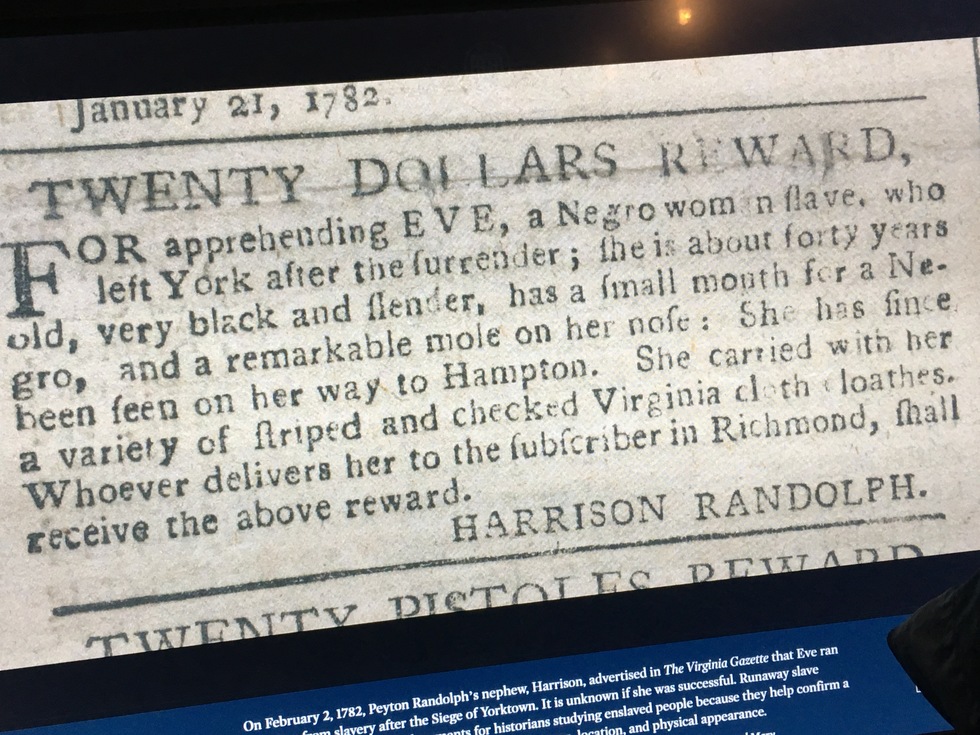

African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans fought on both sides of the war. For the enslaved, it was by no means an easy task to figure out which side was for freedom. The Americans espoused the rhetoric of liberty, but some in slavery decided that their best chances lay with those battling their masters. In Virginia, the colony’s last royalist governor offered freedom to anybody in slavery who took up arms against the colonists. Others took advantage of the war’s chaos to attempt escape, as in the case of Eve, the fortysomething Virginian mentioned in the newspaper ad pictured above. Noting that Eve fled Yorktown after the British surrender, her former owner offers a $20 reward for her recapture.

So potent a symbol was the tent that it was carefully preserved at Mount Vernon after the war and passed down, generation to generation, in Martha Washington's family. Here's where the story gets weird: During the Civil War, the tent ended up in the home of Mary Custis Lee, great-great-grandaughter of Martha, and wife to Confederate General Robert E. Lee. When Arlington was confiscated by the Union, so was the tent, which was then displayed in Washington, D.C., as a tool to rouse support for the Union cause. Eventually, the tent was returned to the Lee family, which then sold it to raise money for a charity for Confederate widows.

The tent is the museum's Mona Lisa and displayed during a compelling video presentation. The public only gets to see it for one minute and 56 seconds at a time, because the fragile artifact is made of linen and too much light would degrade it.

Fun fact: The tent isn't actually being held up by the displayed stakes, ropes, and poles. Instead, engineers designed a custom interior scaffolding. That design, and the restoration work done on the tent, took approximately four years.

Second fun fact: The origins of the tent are unknown. Some experts think this most American of artifacts was likely imported from Turkey.

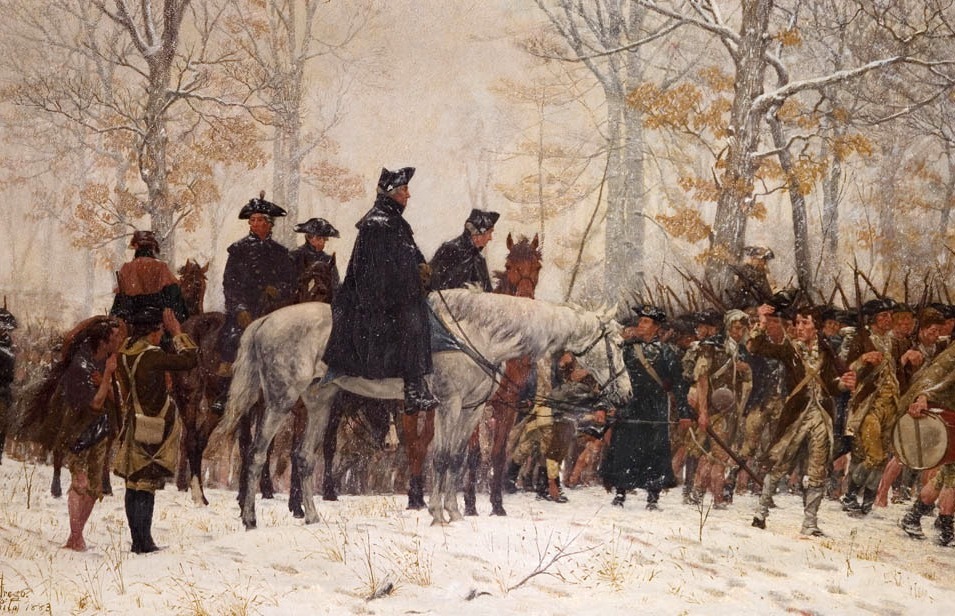

As leader of the Continental Army, Gen. Washington pulled off one of history’s great upsets, defeating a much stronger and better funded European superpower. But from many of his letters, you get the impression that even Washington thought victory for the Americans seemed awfully farfetched. During the brutal winter he spent with his troops at Valley Forge, the general wrote to the Continental Congress that, as he saw it, the army was bound “inevitably” to do one of three things: “starve, dissolve, or disperse.” Of course, Washington began to turn things around after that, but even in 1781—six years after the start of the conflict and still two years from the treaty that would end it—he was lamenting that “we are at the end of our tether, and that now or never our deliverance must come.” Clearly, victory was never assured.

Pictured above: The March to Valley Forge (1883) by William B.T. Trego; on display at the Museum of the American Revolution

When the British army occupied Philadelphia starting in September 1777, they overtook Independence Hall—then known as the Pennsylvania State House—and turned it into a prison for American officers and a barracks for redcoats. We’re talking about the same building where the Founders declared independence in July 1776. And now, just 14 months later, this symbol of freedom was a prison. You kind of have to admire the perverse symbolism of it. When the occupation ended some nine months later, it was discovered that the hall’s stately interior had been trashed and the furniture burned. The museum has a tableau showing that sorry scene; the real Independence Hall, meanwhile, is just a 5-minute walk west on Chestnut Street (it’s pictured above).

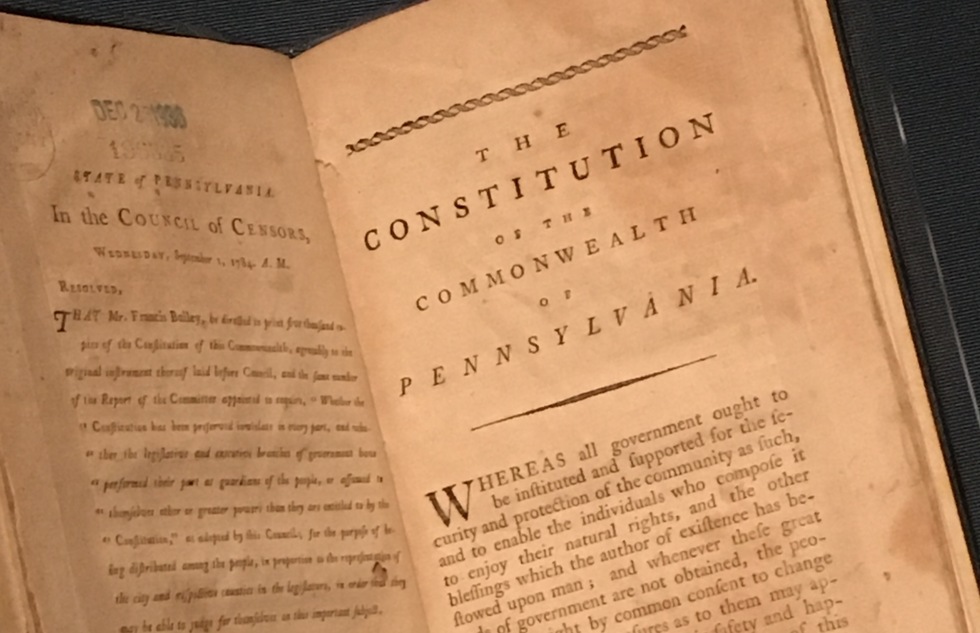

Recognizing the need to create their own systems of republican government replacing royal authority, the original colonies ended up drafting the world’s first written constitutions. In fact, 11 of the 13 had done so by 1780—seven years before the creation of the federal constitution. Though that document ended up overshadowing its predecessors, some of them went surprisingly far in the direction of true democracy. For instance, Pennsylvania’s 1776 constitution (pictured above) called for no governor or senate so that a single legislative house would be sure to reflect the will of the voters. Translations were published in Europe and praised as an example of bold American thinking.

For more information or to buy tickets, go to AmRevMuseum.org.