Mackinac Island: Lost in Time

By Pauline Frommer

Gone with the Wind has the largest movie fan club in the world. What comes in second? It isn’t Star Wars or Titanic. No, that honor belongs to a film that was a commercial flop initially, but achieved cult status over the years: the 1980 Christopher Reeve/Jane Seymour romance Somewhere in Time. It was filmed on Michigan's Mackinac Island, a place that could be said to have achieved its own cult status, albeit over hundreds of years instead of a couple decades. What has kept this little 4-mile slip of land in visitors' hearts for so long? Read on.

The island's first visitors

The first visitors to Mackinac Island were the Great Lakes Native Americans, most prominently the Ojibway and Odawa peoples. The island is at the heart of a massive liquid highway, located in the straits of Mackinac (pronounced mack-in-aw), the waterway that connects Lake Huron with Lake Michigan. During the Woodland Period (1000 B.C. to 1650 A.D.) nomadic tribes used the island as a centralized meeting place and fishing grounds. The waters around here were so crowded with trout, whitefish, pike, sturgeon, and herring that native peoples called this the "land of the fish."

But Mackinac was more than just an open-air restaurant to its earliest human visitors. It was considered a sacred place. Legend has it that the rock formation pictured here is actually a portal to the spirit world. It was through this portal that the world was created. Today, Arch Rock is still a star attraction, accessible via an easy hiking trail or stairs that rise from the circular road ringing the island (the entry is well marked).

But Mackinac was more than just an open-air restaurant to its earliest human visitors. It was considered a sacred place. Legend has it that the rock formation pictured here is actually a portal to the spirit world. It was through this portal that the world was created. Today, Arch Rock is still a star attraction, accessible via an easy hiking trail or stairs that rise from the circular road ringing the island (the entry is well marked).

Abundant nature

It's not hard to imagine what the island would have looked like before the Europeans showed up, since 83% of Mackinac is protected from development. That's not a fluke. The island was the second place in the United States, after Yellowstone, to be designated a national park. Today it's a state park and still wonderfully serene and green.

No cars allowed

The other element that takes visitors back in time is the island's long-standing ban on cars. In the late 1890s, the horse-and-carriage concessioners on the island used their political clout to keep out their metal competitors. Visitors today get around by bicycle, horseback, or carriage. And that over-a-century-old ban means that the streets are cozy and narrow because they were never widened to make way for automobiles. The car-free landscape was one of the primary reasons the makers of Somewhere in Time decided to film here. M-185, the ring road that circles the island, is the only U.S. Interstate that doesn't allow cars.

Experiencing the Native American past today

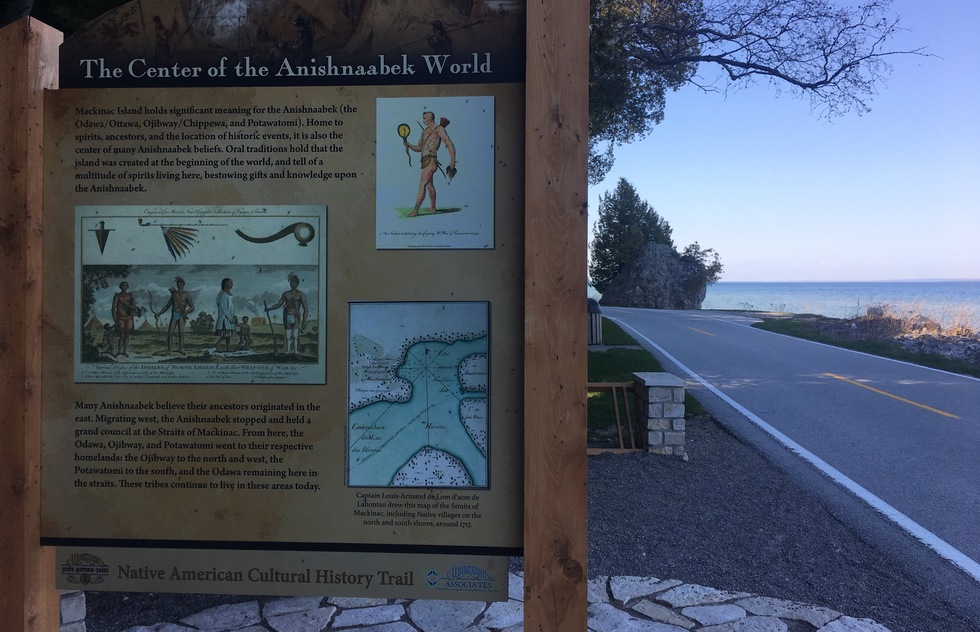

Along the ring road are signs (pictured) with info about the Native Americans who lived part-time on the island for roughly a millennium. These nomadic people left few traces on Mackinac, though there have been some archeological finds of ancient tools and weapons. Stop and read the informative, well-written signs if you're biking in the area.

Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous: Beaver Pelt Edition

The French arrived in Mackinac around 1670 and quickly took advantage of the island's central posiition in the Great Lakes to establish an important fur trading post. It was a huge success and created fortunes. In fact, multimillionaire John Jacob Astor had the headquarters of his American Fur Company here, along with a general store (pictured). That store has been recreated for visitors; here, hunters would trade beaver, muskrat, otter, mink, and fox pelts for pre-made clothing, foodstuffs, ammunition, alcohol, and more. A reenactor helps bring that history to life, including the fact that Astor himself never actually set foot on the island that made him rich.

The military on Mackinac

Within a decade of the first temporary European settlements, Mackinac caught the eye of the French government, which built the first fort in nearby St. Ignace in 1680. This was the beginning of 200 years of military encampments. Fort Mackinac, pictured above, was built by the British in 1779; they knew that a deep harbor and limestone bluffs would make the island hard to capture. The fort is central to the visitor experience today.

Historic reenactments

From May through October, the fort thunders with the hourly sounds of cannon fire and rifle shots. Historic reenactors march in formation, demonstrate weapons, and chat with visitors about what life would have been like when the place was abuzz with soldiers awaiting an invasion.

A famous battle

And sure enough, an invasion eventually came. The fort was taken from the Americans by the British in the first land battle of the War of 1812. The British caught the Americans off-guard, storming the island with a troop of 600 fighters—400 Odawa, Ojibway, Winnebago, Dakota, and Menominee warriors, plus 150 French-Canadian mercenaries and 50 redcoats. They badly outnumbered the 60 Americans guarding the fort, who were eventually forced to surrender. A number of the rooms in the citadel are dedicated to telling the tale of that storied battle, using sculptures, immersive sound effects, and wall text. As it happened, the Americans never won the fort back, though they tried. It was finally ceded to the United States by treaty after the war.

Life of a soldier

The most compelling sites at the fort are those that show what daily life would have been like. The curators have done a bang-up job telling the stories of these soldiers with talking 3-D projections (pictured), soundscapes, wall text, and artifacts. In the hospital, which is the oldest standing hospital in Michigan, a projection of a modern-day doctor explains what would have beeen the most common illnesses and what doctors could and couldn't do to treat their charges. At the jail you'll learn about the brutal way would-be deserters were punished; look down and you'll see a slab of glass covering the deep but narrow hole where men were tossed for days at a time for various infractions. Barracks filled with rough beds and few comforts sit beside elegant officers quarters, decorated with finely upholstered chairs and burnished wood furniture. It's quite the contrast.

The fort was decommissioned in 1895, though by that time soldiers were primarily working as rangers in what was then America's second national park.

The fort was decommissioned in 1895, though by that time soldiers were primarily working as rangers in what was then America's second national park.

An unexpected science lesson

Another worthwhile stop is the small museum devoted to the work of Dr. William Beaumont; it's located right off the general store pictured earlier. In 1822, a 19-year-old fur trapper named Alexis St. Martin was accidentally shot in the stomach at the general store. Though the young man wasn't expected to survive the night, the fort's surgeon, Dr. Beaumont, dressed and cleaned his wounds as best he could (see the painting above). When he arrived back the next morning, he found to his surprise that St. Martin was sitting up and talking. The physician tended to the patient over the next several weeks and eventually the wound healed—in a fashion. Somehow the wall of the stomach became attached to the skin, creating a flap which could be lifted up so that one could peer into the fur trapper's gut.

In that era, the workings of digestion were a mystery. Dr. Beaumont, sensing a scientific opportunity, started experimenting on the young trapper. He withdrew gastric juices from the stomach to see how they worked when he mixed them with organic matter. Or he'd drop bits of food into the hole on a silk thread to observe what happened. These ethically questionable experiments continued on and off for 10 years, much to St. Martin's growing annoyance (can you blame him?). Still, Dr. Beaumont's discoveries formed the foundation of what scientists know about the stomach. Who knew you could learn so much about gastroenterology on Mackinac Island?

In that era, the workings of digestion were a mystery. Dr. Beaumont, sensing a scientific opportunity, started experimenting on the young trapper. He withdrew gastric juices from the stomach to see how they worked when he mixed them with organic matter. Or he'd drop bits of food into the hole on a silk thread to observe what happened. These ethically questionable experiments continued on and off for 10 years, much to St. Martin's growing annoyance (can you blame him?). Still, Dr. Beaumont's discoveries formed the foundation of what scientists know about the stomach. Who knew you could learn so much about gastroenterology on Mackinac Island?

Tourists descend

By the 1830s the fur trade was at an end, and the island turned to a new pursuit: tourism. Over the years, and especially after the Civil War, the island's balmy breezes, Native American inhabitants (who sold crafts in the early years), historic fort, and pristine wilderness areas proved irresistible to Midwestern vacationers. They came here in droves, along with such bold-faced names as Alexis de Tocqueville, Harriet Martineau, Ernest Hemingway, William Cullen Bryant, and five U.S. presidents—Truman, Kennedy, Ford, Bush, and Clinton. Many of the wealthiest citizens of Chicago and Detroit built magnificent Victorian retreats here (pictured) that they modestly called "cottages." One of them is still a summer residence for the governor of Michigan.

Souvenirs worth saving

When Mackinac became a resort it went all in, and souvenirs became a big part of the economy. They ranged from what were then called "Indian curiosities" (corn husk dolls, maple syrup, and more) to museum-worthy pieces like these exquisite etched glasses. Visitors to the island could have their names and other bits of text inscribed on them. Handsome painted plates showing scenes of the island, these gem-colored glasses, and more are displayed in the Richard and Jane Manoogian Mackinac Art Museum, which also features more standard works of art showing scenes of island life through the ages.

Fudge!

One souvenir that rarely makes it off the island—because it's usually devoured first—is the famously irresistible fudge. The candy was popularized by Henry Murdick, a confectioner and sail-maker who was brought to Mackinac in 1887 for his skills with canvas. He created the first awnings for the island's famed Grand Hotel (more on that lodging next). He opened his first candy store in 1889, drawing in customers with his theatrical technique of tossing the cooling fudge above a marble slab until it formed a log ready to be cut. As you can see, island candy makers still use that same technique and market their wares in the same way, too, making sure that the street outside is perfumed with the aroma of chocolate.

The Grand Hotel

In the old days, most visitors came to Mackinac on a combo ticket, first taking the railway and then boarding a ferry. To encourage even more riders, the railways followed their custom in many places across the United States: They created a destination hotel. The Grand Hotel, built in 1887, lived up to its name. Created to dazzle, the massive wooden structure featured elaborate gardens, multiple eateries, a grand ballroom, live music, and a golf course. It was one of several hundred magnificent pleasure palaces created by the railways during the Gilded Age. Alas, there are just 11 left in the United States.

Pictured here is the lobby. Many scenes from Somewhere in Time were filmed at the hotel; every October, fans of the movie gather to dress in period costumes, meet cast members, and hobnob. Another cinematic claim to fame: The hotel's swimming pool is named for MGM's queen of the aqua ballet, Esther Williams, who shot a scene here in 1947.

Pictured here is the lobby. Many scenes from Somewhere in Time were filmed at the hotel; every October, fans of the movie gather to dress in period costumes, meet cast members, and hobnob. Another cinematic claim to fame: The hotel's swimming pool is named for MGM's queen of the aqua ballet, Esther Williams, who shot a scene here in 1947.

The famous porch

Management at the Grand Hotel claim that the porch is the longest in the United States. It certainly feels that way when you're sitting in one of the rocking chairs, watching the American flags that front the hotel flutter and the crystalline lake beyond ripple in the wind.

Presidential digs

Many of the Grand Hotel's suites are named after U.S. first ladies, who are invited to collaborate on the design. You may have guessed from the peachy color scheme that this is the Rosalynn Carter suite.

The "Somewhere in Time" gazebo

For those who are wondering: Yes, the romantic gazebo from the film is still on the island. It's been placed in a secluded open spot in the state park and can be reserved for weddings and other events.

Old-school golf

Mackinac has three place to tee up, but the most evocative is the Wawashkamo Golf Course. One of the few links courses left in the United States, it looks just as it did when it was built in 1898. That means golfers have the opportunity to play on a course identical to those their great-grandfathers would have experienced, with very different types of obstacles and traps than what we're used to today. The cannon you can see above and a memorial plaque pay tribute to those who died on this spot during the battles that took place during the War of 1812.

Old-school golf clubs

Those who really want the old-fashioned golf experience can rent hickory wood clubs. Wawashkamo is one of the few places in the United States where these hand-hewn clubs are available to guests.