Experience the Subterranean Beauty of India's Lost Stepwells

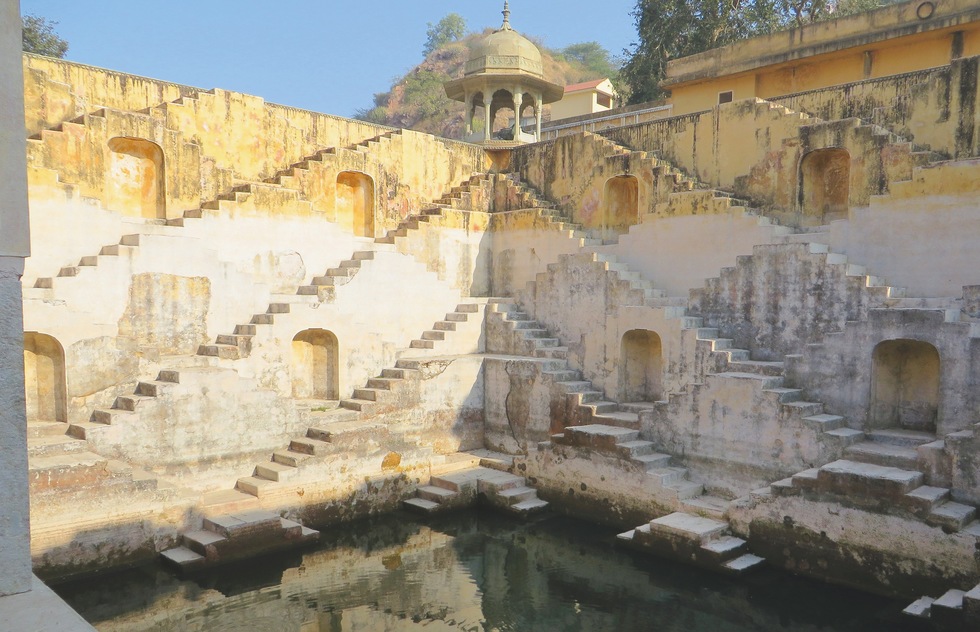

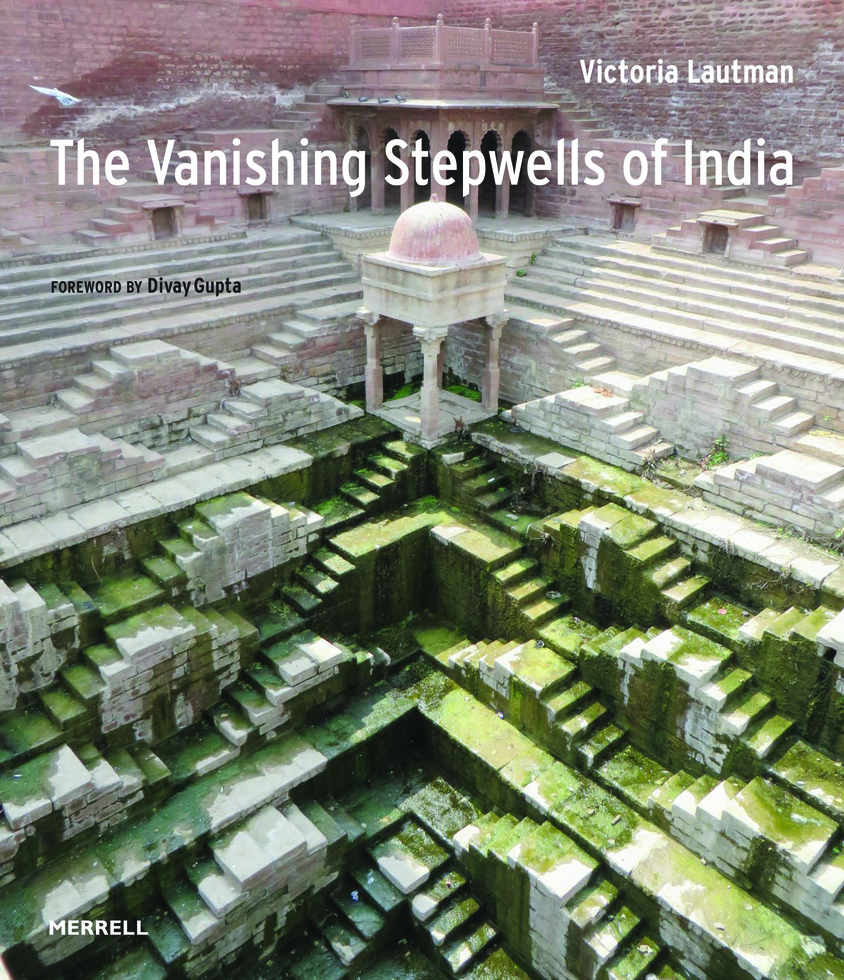

By Frommer's StaffFirst appearing around 1,600 years ago, stepwells are thought to have numbered in the thousands by the 18th century. By the year 800, they had evolved into astonishing marvels of architecture, engineering, and art that served many other functions than simply providing water. They could be active subterranean temples, cool rest stops along trade routes, private retreats, or simply social gathering places. But there’s little documentation about these fascinating structures. Despite their former importance, most stepwells have sunk into obscurity, even though many are close to popular tourist destinations. In my recent book, The Vanishing Stepwells of India, I trace the history and wide-ranging styles of these incomparable edifices. What follows is a sampling of some of the most fascinating.

There are plenty of macabre stories associated with stepwells, usually featuring ghosts, curses, suicides, or sacrifices. An example of the latter pertains to this well, where two virgins named Adi and Kadi are said to have been drowned to ensure the uninterrupted flow of water. Since this stepwell was built at the imposing Uparkot Fort in Junagadh, that was of particular concern—sieges often lasted many years and people couldn't venture far for hydration. The structure is extraordinarily simple. It's just a long, narrow, open corridor with shallow steps, all carved directly into the local limestone and terminating in a watery pool. But it’s a singularly eerie place, where the towering, deeply eroded limestone walls and the echoes of flapping pigeons could easily stimulate nightmares or ghostly tales.