It's difficult to imagine, but put yourself in the 1930s. There was no television and there were no jumbo jets. Ocean liners took days to cross the Atlantic, letters took weeks to be delivered, and for your entire life, you would have little chance to glimpse other countries with your own eyes. It was an era when the only reason an average person might travel overseas would be to fight in a war.

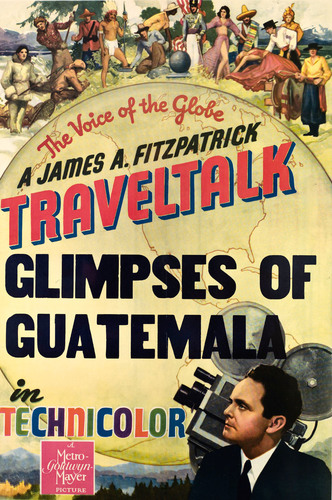

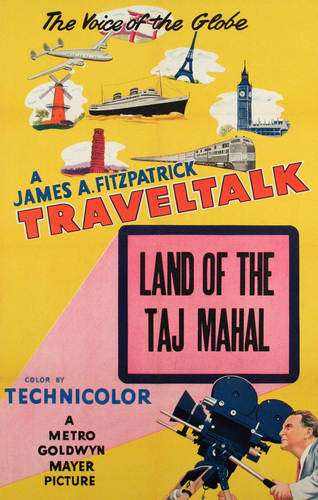

If you grew up in that period, your first exposure to many foreign countries came through the movies—and the travelogue series that everyone trusted was called TravelTalks, made by a man who became world-famous: James A. FitzPatrick. Each 10-minute installment showed viewers a new corner of the globe.

Back then, everyone went to the movies. At Saturday matinees, cinemas might kick off a double feature with a cartoon, a newsreel, a two-reel comedy, and a TravelTalks short. In the worst years of the Great Depression, when about 88 million Americans went to the pictures every week, TravelTalks was as much a staple of pop culture as Mickey Mouse or the Three Stooges.

MGM released FitzPatrick's first TravelTalks film, “The Land of the Maharajahs,” on August 2, 1931, just as a shattered economy made global travel an impossibility. For nearly 25 years, FitzPatrick brought his fellow Americans more than 200 additional installments, circling the world six times and traversing more than half a million miles.

In 1938, FitzPatrick's contract with MGM paid him $80,000 (about $1.4 million today) to make 12 one-reelers a year. During the scant three months of the calendar when he was back home in Beverly Hills, he played golf with friends like Clark Gable.

FitzPatrick's wife accompanied him on trips, acting as his professional assistant. When their kids were old enough to help lug the heavy camera batteries around, they were invited to join. FitzPatrick only stopped making new travel shorts in the mid-1950s, when television could finally beam images of the world directly into every home. By then, though, he had set the tone for travel documentary films, a style still familiar today.

James A. FitzPatrick was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960. Yet despite their former ubiquity and the lifeline they provided to generations of travel lovers, TravelTalks are mostly forgotten today.

The first travel influencer

FitzPatrick, born in 1902 to Irish parents in Connecticut, struggled in other entertainment jobs before landing, at age 35, on the niche that would make him famous.

MGM's nickname for FitzPatrick, "The Voice of the Globe," wasn't overstating his popularity—British newsreels called him "the owner of a famous voice known to all film fans."

(James A. FitzPatrick: MGM publicity image)

(James A. FitzPatrick: MGM publicity image)

Today, you can catch FitzPatrick's adventures on the Turner Classic Movies channel, where 193 titles from the series frequently surface when there's time to fill between feature films. Mostly, TravelTalks aren't listed in the schedule, but now and then—in a nod to program-packed bills at movie palaces past—the shorts are announced as part of the Saturday Matinee programming block (8am to noon ET).

In 2016, the Warner Archive Collection issued 186 TravelTalks in three DVD volumes, but for the most part, this once-essential American institution has faded into the obscurity where all cultural ephemera vanishes.

Viewed now, the shorts are both elevated and hobbled by the conventions of their day. FitzPatrick's clipped and stentorian diction, drenched in poetic turns of phrase and purple hyperbole crafted to inspire, hearkens to a time when talents practically had to shout to overcome the limitations of primitive audio systems. Yet FitzPatrick's delivery came to define the style of the filmed travelogue as definitively as David Attenborough's narration of animal life seems indispensable in nature films today.

Like our own era's social media influencers, FitzPatrick worked in a short-form video format, with dispatches lasting 8 to 10 minutes apiece. Out of fear of not being invited back to whatever place he was visiting, the host generally sidestepped social or political strife to paint a relentlessly enchanting picture of even the most troubled locales.

FitzPatrick often appeared in his own shots, but he never indulged himself as a center of attention; to him, the destination was the object of fascination. To stir audiences and make them feel part of the journey, FitzPatrick's voiceovers were in the first-person plural: "We are sailing now down the swift-flowing Rhine," he might say, or "the breezes which flow from the island of Java waft an enticing fragrance to our ship."

Luckily for him, FitzPatrick had at his disposal the full resources of MGM's Culver City production factory. Each edition was scored with a full orchestra, and the directors of photography included Jack Cardiff, who later shot Black Narcissus and The African Queen and is widely considered to be one of the best cinematographers in film history.

When FitzPatrick decided to abandon black-and-white film stock to capture the Netherlands' 1934 flower crop using Technicolor's new three-strip process in "Holland in Tulip Time," the indulgence put TravelTalks ahead of mainstream Hollywood production by several years. MGM's Technicolor epic The Wizard of Oz was still five years away.

Visions of a lost world

Though the filmmaking technique was ahead of its time, many of FitzPatrick's observations were not, often dwelling on reductive cultural stereotypes. In a film about Algeria, we're told the Berbers only looked "colored" but were in fact as "racially as white as ourselves."

In 1934, South Africa is hailed as "a grand tribute to the colonizing genius of the white man" who transformed "a barbaric wilderness." Eighteen years later, FitzGerald returned to the nation, then under Apartheid, to ladle praise upon segregationist Cecil Rhodes and film a Black woman doing back-breaking work in a Constantia vineyard with an infant strapped to her. The narration chipperly admired how the "natives," as he called them, "have had the advantage of learning their trade at a very early age."

Today, we recognize pronouncements like those as so myopic and casually dehumanizing that they could be lampooned as camp. At times, FitzPatrick's blindered perspective has the potential of making you a better traveler through negative example alone. Yet at other times, his respect for other cultures appears to run deep and true, and it can be hard to separate what he actually believed from what he thought his less-traveled audiences wanted to hear.

It's the visuals of TravelTalks, though, that are harder to leave behind. On purely documentary terms, the films endure as essential historical artifacts, allowing us to gaze at locations, customs, and attitudes that were subsequently reshaped and scarred by the upheavals of time.

Some of the places and lives captured were never filmed again, turning these shorts, which were once consumed as thoughtlessly as popcorn, into priceless encounters. We can visit the lost hutongs of Peking, Nevada before the Vegas Strip, Paris before the Nazi invasion, Korea before division, and Japan before the atom bombs.

Even as the TravelTalks films remind us how we can improve as cultural observers, they still light the flame of wanderlust—though with the elegiac pang that accompanies lost time. Just as they did for the audiences they were originally made for, these movies show us the way to a world we'll never be able visit in person.

(Poster images courtesy of Turner Classic Movies)