Pauline: We have a true adventurer with us. His name is Peter Milligan, and he is the author of a new book Bulls Before Breakfast: Running with the Bulls and Celebrating Fiesta de San Fermín in Pamplona, Spain.

Milligan: I've carried a Frommer guide in my backpack for 25 years, so I'm very excited.

Pauline: Thank you so much. You put me through college! I guess before we get to the question of whether you have a death wish, and how your wife tolerates you constantly doing this fiesta where you run before dangerous bulls, can you tell us a little bit of a background of the Fiesta de San Fermín?

Milligan: This started in Northern Spain in the Kingdom on Navarra. They started a Catholic festival to honor the patron saint of Pamplona who is Saint Fermín. It started out as purely religious but they began to add days over the decades and centuries and at some point they decided to bring bulls into town to have a bullfight fair. They had a problem: The Romans built the bullring too far from the river, so they brought the bulls from the ranch to town on river barges. They had to sneak the bulls through town under the cover of dawn to the bullring.

Pauline: How many centuries ago are we talking?

Milligan: At the very least this is a 1,500 year old festival and there is some debate over whether it's older than that. They did not keep notes. The Spanish were not a recorded history culture. They were an oral history culture. The modern bull-running course started on July 7, 1776.

Pauline: 1776, a big year for us in America! Why did they start to run with the bulls into the arena for bullfighting? How did that decision get made?

Milligan: Well it started out with the butchers wearing their white aprons. That's why they wear the white pants to run with the bulls: The butchers would sneak out the door and get out there with them just for the thrill of it. There were wild bulls in the Pyrenees forest in the mountains back then, and they'd stumble across them much like you'd stumble across a bear on the Appalachian Trail.

Pauline: In 1776 they started running with the bulls?

Milligan: Well they formed the modern course they have been running through town for hundreds of years before then. The course we run today, where the fences guide us to the bullring, is as old as the United States.

Pauline: I think people don't understand that it is a course. Most people just think it's one long street. Not only do you go through a complex trail through the town but it's also done not just on one day, but for eight days right?

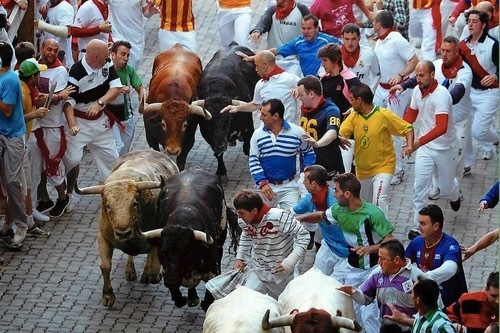

Milligan: It's done every morning at 8 o'clock from July 7th to July 14th, and they run six bulls every morning with six steers. The steers know the way, so when the steers run the bulls tend to follow them as they guide them around farms and through the city. The track is about a mile long, the bulls run upwards of 35 miles an hour, and they weigh upwards of a ton. You cannot run with them the entire length, you can run maybe 25 or 30 yards in front of them before their speed will overtake you.

Pauline: So the runners are ahead of them on the trail, because if they were right on top of them they'd all be gored. A rocket goes off which alerts the runners that the first bull has left and you say a second rocket goes off when the last bull has left and experienced runners listen for that because if the bulls get separated it means really bad things can happen. Why is that?

Pauline: So the runners are ahead of them on the trail, because if they were right on top of them they'd all be gored. A rocket goes off which alerts the runners that the first bull has left and you say a second rocket goes off when the last bull has left and experienced runners listen for that because if the bulls get separated it means really bad things can happen. Why is that?

Milligan: Well, the bulls are by instinct herding animals, they keep together, and these bulls in particular have been with each other since at least their first birthday on whatever ranch they come from throughout Spain. They know each other, and while they might bicker, we just see them poking each other with their horns. They are in essence, brothers, and the Spanish culture looks at them as brothers, so they tend to stay together. If one gets separated, they panic and they get a little bit nervous, and they exhibit that by going to investigate the various runners and whether they can get to them. It's always better if they stay together. If you're running with the bulls and you hear the locals start yelling suelto, which means lone bull, it means a very dangerous activity has become that much more dangerous.

Pauline: That leads to the question, why have you done this so many times? You've done this run over seventy times according to the book, what is the appeal?

Milligan: I went to Spain with my brother, to Seville, to see the tomb of Christopher Columbus. We're both very big Christopher Columbus fans, then we saw on the calendar, hey it looks like they're doing that bull thing up in Pamplona the same period of time that we're there. So let's start in the town and see what's up. We did it the one day, and that first run was the machismo run: Let's see if we can do this, see if we can be brave enough to get out there. Then we learned there's a lot more to it than the experience of say, jumping out of airplane, things that people do for a thrill. There was much more than a cheap thrill to it. There's a joy, a sense of brotherhood among the runners. We look it as a sport in the U.S., they look at it more as ballet or dancing. It's something to be refined and perfected in your years of trying to get between the horns.

Pauline: So you say locals see it almost as a dance, almost like ballet. I know in your book you talk about the reason you've done it so many times is you have this quest to have the perfect run. What would be the perfect run when you're running with the bulls?

Milligan: Well, when you run, they're coming at you very quickly and you try your best to get out and fight through the crowds, and you fight through the crowd to get as close as possible to the bulls. The goal is not to touch them or to hit them with the newspaper that the runners hold in their hands. The goal is not to touch their horns or distract them in any fashion. The goal is to join them. Running next to them is perfectly acceptable and I've done that dozens of times and it's quite a thrill. Anyone who gets out there and does any amount of running at all near the herd has run with the bulls. For me, the perfect run would be to get out in front and find an area bereft of other runners and get in between the horns right in front of the herd and lead them into the bullring as close as I can be without getting run over.

Pauline: Have you achieved that yet?

Milligan: No, not even close. I've been between the horns many times and most of the time for a fleeting moment. It feels like it's 15 minutes when I'm running and you look at a video later on and you realize it was three to five seconds.

Arthur: Peter how do you escape being gored? At some point do you leap over the fence to your left to escape those dreadful horns?

Milligan: For the most part you ease over to the left or the right, which is very difficult because there's a lot of panicked runners and there's people yelling and screaming. There's a lot of people who have decided maybe this wasn't such a good idea and they're trying to climb over the fences. The fences are for absolute emergencies. You and I would say an emergency is an approaching dangerous Spanish bull but they see an emergency as something much, much worse. For the most part they'll push you back if you try to climb the fence too early. You try to ease off to the left or right and hope that that the bulls maintain their herding instinct and don't come over closer to investigate. Both my brother and I have been injured. He's been gored in the leg. I've never been gored, but I've been smacked with the horns, I've been head-butted by the bulls, I've had broken bones, but I've never had the misfortune of taking the horns yet.

Arthur: Peter, how many people are actually injured and how frequently are they injured?

Milligan: Every day, every day people are injured. If it's not falling or getting crushed by other runners, or tripped by other runners, the bulls get someone. The bulls very rarely have a complete clean run. At most one or two people are gored per day. This past fiesta it seemed like every day somebody was gored. We hope for a clean run every day but cobblestones are hard and those horns are sharp and everybody is throwing elbows—so something is bound to happen.

Pauline: If somebody wanted to go and witness it and not run, how far in advance do they have to book a hotel room? Is it better to do maybe the seventh day of the fiesta than the first? What are quick tips for people who want to see this in person?

Milligan: Well, it's every July and to be assured of a decent hotel room, you want to start looking in the fall before fiesta. We make our reservations in September if we don't make them when we're leaving Pamplona. At the very latest we make them by October. We start making dinner reservations in the winter time. The part of the fiesta where there's the least amount of people is away from the weekends. The weekends tend to bring in people who can drive in locally. On the weekend nearest Bastille Day the French pour over the border in the hundreds of thousands. Weekdays are the easiest to get reservations and frankly this most enjoyable part of the fiesta because it is not as crowded.

Pauline: It's a beautiful medieval town right? So any time of year you should go to Pamplona even if you can't make it during this festival?

Milligan: It's a fantastic town. There's universities up there so there's always things going on. They have a marathon, they have a wonderful Christmas Eve and New Year's Eve celebrations where everybody pours out of the town and there's parades and there's music. There's the Pyrenees are immediately north of Pamplona, so there's epic hiking. There are beaches nearby in the town of San Sebastían.

Pauline: Wonderful food as well. It's a wonderful book that makes you want to go to Pamplona. Thanks so much for sitting down with us Peter.

Milligan: Thank you both, what a thrill for me!

This interview was broadcast on our national radio show, The Travel Show.

For more information on Peter Milligan's book check out his webisite, bullsbeforebreakfast.com.

Photo credit: Peter Milligan

This interview was broadcast on our national radio show, The Travel Show.

For more information on Peter Milligan's book check out his webisite, bullsbeforebreakfast.com.

Photo credit: Peter Milligan