For well over two millennia, humans have been telling one another stories of the dangers of looking back at evil or death. Lot’s wife turned to a pillar of salt because she dared glance over her shoulder into the maw of destruction. Orpheus lost his beloved forever for the same reason: He turned around before he’d reached the realm of light. And in a case of real life imitating, well, iconic tales, on September 11, 2001, those people who were on the streets surrounding the Twin Towers when they fell, had to run for their lives to escape the deadly debris cloud that pursued them with unrelenting fury. “Don’t look back, just run” one bystander yells to another in one of the many moving videos at the 9/11 Memorial and Museum.

For over a decade it looked like the survivors, politicians, and others who had vowed to create this museum might not actually have the ability to look back at that world-changing September day. Bickering over every element of the design and contents of the museum caused endless delays and became newspaper fodder; controversies seemed to erupt daily over such issues as the high cost of entry to the museum, its portrayal of the Muslim religion, even the fact that it had a gift shop.

Yet despite all this, the 9/11 Museum has emerged as what may be one of the most important history museums in the United States. Out of all the chaos and well-publicized postponements comes an institution that seamlessly blends design and content, transporting visitors back, in a very visceral way, to the day in which four separate, airplane-fueled attacks killed close to the 3,000 people (the museum relates the stories not just of the Twin Towers, but also of the Pentagon attack and Flight 93).

After a thorough security check (make sure you allot 15 minutes minimum for that and the line to get in), visitors descend down, down, down, into this underground museum. It’s a fitting metaphor for both the escape route survivors of the Twin Towers had to take when fleeing by stair (a remnant of the famous “survivors stair” is to the right of the museum’s staircase at one point) as well as the darkness the attacks plunged the United States into. At the bottom of the final staircase, to the left (oddly, as most visitors want to turn right), is the museum’s beating heart: its history exhibition. A masterful mix of video, audio clips from survivors, wall text, and poignant artifacts—the burnt-edged papers that fluttered from the Towers, children’s clothing recovered from Flight 93—the exhibit manages to both bring to life the personal stories of those who lived or died that day, and explain some of the forces that shaped the attacks. A thought-provoking section explores the rise of Al Qaeda (you even see a brick from Bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound at the museum). The lingering health issues that survivors and first responders still struggle with is explored, as is the issue of who, beyond the attackers, should be held accountable. Museumgoers also see the famous Ground Zero cross (metal beams of the structure that were broken off into this Christian symbol), a squashed fire truck, and the Memorial Room, which tells the story and shows the face of every person who died on 9/11.

I, for one, am glad that the founders of the museum were finally able to look back and to do so in such a clear-eyed, multifaceted way. I don’t know if the museum has one over-arching point to make, but it offers revelations at every turn about our recent history and the men and women who shaped it. And everywhere are boxes of tissues (refilled every hour, according to the guard I spoke with) as the museum is ultimately quite an emotional experience.

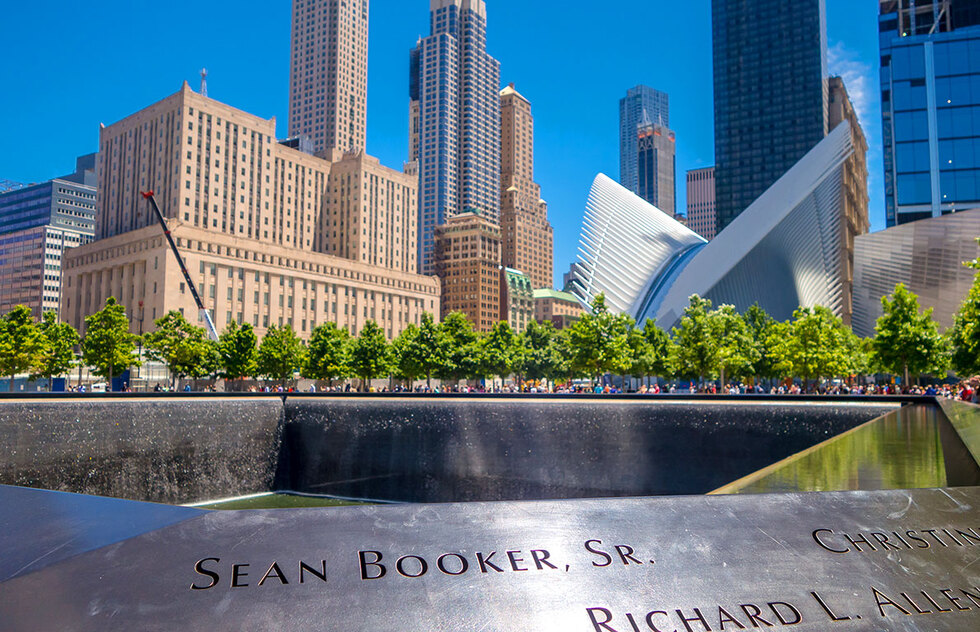

Surrounding the museum is the 8-acre Memorial Plaza, which features two reflecting pools and waterfalls, located in the 1-acre footprints of the individual towers. Each reflecting pool is surrounded by a brass parapet where the names of the victims of both the 9/11 and February 1993 bombings are engraved and arranged in an order as to where they worked, close to their co-workers or friends, or wherever their families thought they could best be located.

About our rating system

About our rating system