Père-Lachaise Cemetery, Paris: The World’s Most Legendary Necropolis

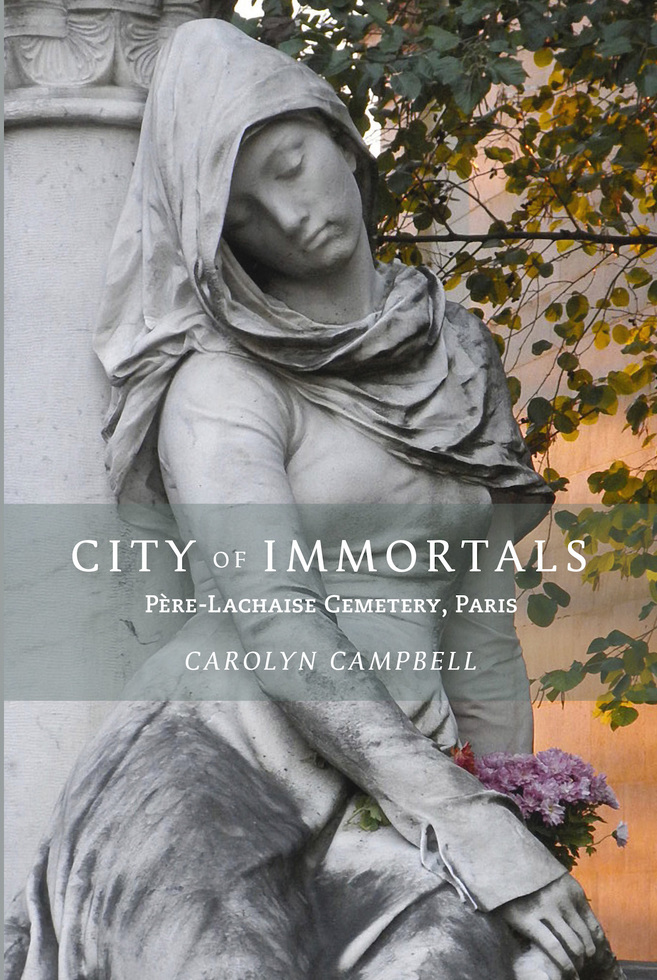

By Carolyn CampbellArguably the most famous resting place in the world, Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris is also a vital tourist attraction, receiving some 3.5 million visitors each year. Carolyn Campbell's book City of Immortals explores the 107-acre labyrinth from its architectural and sculptural treasures to the graves of 84 cultural icons.

Carolyn Campbell is the author and photographer, along with contributing photographer Joe Cornish, of City of Immortals: Père-Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, from Goff Books.

Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris is no ordinary necropolis; it is a 107-acre labyrinth housing a timeless “salon” of luminaries from the worlds of art, design, literature, and the performing arts, including Sarah Bernhardt, Frédéric Chopin, Eugène Delacroix, Jim Morrison of The Doors, Edith Piaf, Marcel Proust, Gertrude Stein, and Oscar Wilde. Since many of the tombs and monuments were designed by notable artists and architects of the period, it is a magnificent open-air museum of sculpture and architecture spanning more than two centuries of art history.

On my first visit in 1981, I became enthralled with the cemetery’s rich history and artistic significance. Three decades later, I am still captivated by its ever-changing beauty and mystery. In my book, City of Immortals: Père-Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, I am thrilled to share the story of this grandest of all graveyards.

Honoré de Balzac once said, “I seldom go out, but when I feel myself flagging I go out and cheer myself up in Père-Lachaise… while seeking out the dead I see nothing but the living.” Balzac himself is one of the many prominent souls in this world famous destination, the fourthmost popular site in Paris after Notre Dame, the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe.

By the end of the 1700s, centuries of war and plague had already filled the catacombs and church graveyards across Paris. Eighteenth-century Parisian engineers had overlooked one significant question in their urban design scheme—what to do with the ever-increasing population of the dead? In 1799, Napolèon Bonaparte directed Nicolas Frochot, Prefect of the Seine, to hold a competition to create new cemeteries on the outskirts of the city. The commission was awarded to architect and landscape designer Alexandre Brongniart. Frochot had a keen sense of how to appeal to the masses by creating something intriguing. He convinced Napolèon of a plan to win over all the critics as well as the hesitant clientele by naming the cemetery after Père Lachaise, priest confessor of the popular Sun King Louis XIV. He launched an inventive real estate promotion filling the cemetery with the remains of the famous and infamous, including Molière and La Fontaine. The grand opening of Père-Lachaise Cemetery was held on May 21, 1804.

Étienne-Hippolyte Godde served as the chief architect of the City of Paris from 1813 to 1830. Known for his neoclassic designs, he designed the main Boulevard de Ménilmontant entrance to Père-Lachaise which consists of an elongated horseshoe-shaped driveway with a pair of tall central gates topped by two carved medallions. These bear the classic funerary symbols of the torch (representing life’s flame) and the hourglass (symbolizing the passing of time).

Up the main aisle at the end of Avenue Principale, one encounters the monumental sculpture Aux Morts (To the Dead), created by artist Paul-Albert Bartholomé (1848–1928). Originally designed as a tribute to his wife, the monument features a mournful procession of twenty men, women, and children marching toward an immense dark doorway into the next life. The site also serves as an ossuary that contains the remains of many thousands of Parisians. When other cemeteries in the city were closed or when people’s graves in Père-Lachaise were reclaimed due to negligence or for lack of rent payment, remains were placed in the ossuary. (The ossuary is closed to the public.)

Before becoming the world’s most famous cemetery, the land that became Père-Lachaise was a former Jesuit retreat called Mont-Louis, located in what is now the 20th arrondissement. Reverend Friar François d’Aix de la Chaise (1624–1709), the Jesuit confessor to Louis XIV and the cemetery’s namesake, was a former resident. The bucolic site was planted with lemon groves, rose gardens, tree arbors, and many winding paths ideally suited to the contemplative life of its former inhabitants. The 16 acres of Mont-Louis formed what is referred to as the cemetery’s Romantic Section, which was the original area founded in 1804, and now serves as the resting place for Chopin, Colette, and Gericault.

No expense was spared and no extravagance overlooked in creating what became a revolutionary concept in memorial parks—and a model for many famous U.S. and European cemeteries—with statuary, crypts, and mausoleums designed by the leading artisans of the day. The architectural designs in Père-Lachaise represent an encyclopedic grouping of many periods, including Gothic, Romanesque, Neoclassical, Italian Renaissance, and Art Nouveau crypts next to Egyptian revival pyramids and obelisks. Classical revival treatments as well as Doric and Corinthian columns on mausoleums also appear throughout the cemetery. You would have to zigzag to every corner of Paris to find such a comprehensive collection of examples of the city’s important sculpture and architecture, reflecting periods and styles of art and design from early Roman times to the present. Fortunately, the tombs in Père-Lachaise parallel the city's artistic growth and houses all those styles from the early 1800s onward.

The eternal staying power and drama of funerary monuments appealed to the architects, designers, and artists who contributed to the mesmerizing environment of Père-Lachaise. Their use of funerary symbols such as draped urns, hourglasses, bats, skulls, and mourning figures not only echoed the styling of societal tastes but also delivered on the promise of visceral awe and wonder in the land of the dead.

Statues of women in the 18th century often represented the seven virtues: prudence, justice, temperance, fortitude, faith, hope, and charity—powerful examples of how women are seen to embody some of the deepest qualities of the human condition. In Père-Lachaise, a winged woman symbolizes hope, while charity appears as a nursing mother. The cemetery also has many scantily clad female figures. Sometimes, family members, unaware of the sculptural commission, were alarmed to arrive at gravesites and discover a half-naked damsel in apparent erotic rapture rather than in deep mourning.

The use of skulls or other imagery of death on Père-Lachaise gravestones was discouraged by the City of Paris administrators, who sought to replace Christian-based imagery of macabre sadness with what would instead reflect a more peaceful concept of a sweet rest. After all, the earliest interpretation of the word cimetière was “a place where one sleeps.” Winged cherubs are thus found replacing the death’s head (or soul effigy). Winged figures are generally considered angels, and the word angel comes from the Greek word angelos, which means “messenger.” So the chief duty of an angel was to carry messages from God. At Père-Lachaise, those figures came in many shapes, sizes, and age groups, from a cherub, or putti, to an adolescent to an adult.

Fans and tourists gather to pay respects at the graves of luminaries like Edith Piaf and Frédéric Chopin (two of the most popular Père-Lachaise residents), but it is the final resting place of rock legend Jim Morrison of The Doors that seems to garner the most notoriety as a shrine. On the July 3 anniversary of his death, more than 10,000 visitors line up to pass it, necessitating guards who are stationed throughout the day to monitor crowds.

Sadly, the future is perilous for the phenomenal monuments in the cemetery. Nature is only one of the destructive elements that threaten the thousands of sculptural and architectural treasures of Père-Lachaise. Well-meaning fans mark the tombs with graffiti, which damages the porous surfaces of stone crypts; thieves steal bronze sculptures for their scrap metal, leaving empty niches on the mausoleums of the famous and the bourgeois families. Through fashion and fate, some tombs are slowly disappearing due to fragile materials used in their constructions, the urban plague of vandalism, and acid rain. It required the cooperative efforts of the French and Irish governments to repair Oscar Wilde’s monument (pictured) that was being damaged by the oil in lipstick kisses left by misguided fans. It is now behind a protective Plexiglas case. Visitors may certainly leave mementoes or flowers, but are encouraged not to take any souvenirs or make any markings. The cemetery has survived for over 200 years. We hope it will last for many more centuries so that future generations may pay homage to its legendary residents.