What Aviation Pros Are Doing to Make the Future of Flying More Sustainable

By Pauline FrommerAs climate change continues to wreak havoc across the globe, the pressure is on for the aviation industry to reduce the greenhouse gases resulting from air travel.

Fortunately, there are some smart people working on this knotty problem, and there could be significant improvements in the near future.

That's what I learned during a recent visit to the Rolls-Royce factory in Derby, England. The company creates and maintains the engines for 52% of the wide-bodied jets flying today. An airplane powered by Rolls-Royce takes off somewhere around the globe every 20 seconds.

Consequently, Rolls-Royce has a big impact on aviation worldwide. And right now, the company is working to create engines that use far less fuel and promote sustainability in other ways.

Is the effort entirely altruistic? Of course not. With fossil fuel prices as unstable as they are, aviation business leaders know that moving toward greener sources of energy and methods of propulsion is not only more ethical—it’s better for the bottom line, too.

And Rolls-Royce is not the only manufacturer engaged in this type of work. Rivals are also devising their own green energy fixes, many of which are similar or almost identical to Rolls-Royce's plans.

Since optimism is in short supply these days, I thought it would encourage our readers to know about some of the green aviation innovations in the works for the next 3 to 15 years.

Implementing some of these advances will require governmental support. That's why it's important that citizens of democracies, both here and abroad, develop a solid understanding of this science: so we can elect leaders who will be proactive in creating the infrastructure to support greener aviation.

Behold the propeller of the future. Rolls-Royce has been working for a number of years on what will be the world's largest turbo fan. But it's not only notable for its size (140 inches in diameter, the largest viable size for widebody aircrafts). Once installed, the engine is expected to be 25% more fuel-efficient than its predecessor, the Trent engine. What's more, the UltraFan will be able to run on sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) from day one.

The new engine is also 35% quieter, a big win for communities located near airports. Scientists have found that people who live in flight paths have elevated levels of stress, high blood pressure, and heart disease.

Best of all, the UltraFan produces fewer emissions.

Here's how it's different: The Trent engine and its similar competitors run very fast, taking in a steady, if relatively small, stream of air. The UltraFan, by contrast, will run slower but take in larger amounts of air with each rotation, creating the same amount of power but using less fuel. That trick is pulled off thanks to re-engineered blades that are spaced out more widely, made from a carbon titanium, and sculpted in a shape that supplies more panel area. The gear box that runs the blade has also been redesigned to break aerospce records by delivering up to 64 megawatts of power.

Implementation Plans: Rolls-Royce plans to start testing the fan later this year. At a press briefing, I was told the company hopes to have the new engines in commercial airfcraft in the next five years, but that will depend on when Boeing or Airbus launch new aircraft programs that can incorporate the new technology.

Rolls-Royce engineers also plan to create smaller versions of the UltraFan that can be used in narrow-body aircraft and can even be retrofitted for existing aircraft.

SAFs are created from a number of sources, ranging from reused cooking oils to, unfortunately, palm oil and other plant-based oils, including some that might be needed for human consumption (raising the possibility of ugly future conflicts). These fuels present engineering challenges, however, such as a tendency to get gummy in low temperatures and eat through sealing systems in fuel trucks.

Price is also an issue: SAFs currently cost five times as much as petroleum, primarily because there isn't an infrastructure in place for global distribution.

So, in their current form, SAFs may not be the solution for all aviation concerns.

But some SAF use is clearly a positive because of their low carbon emissions. In fact, SAFs are already being used in blends with petroleum on certain jets.

With its new engine, Rolls-Royce hopes to demonstrate that there are no insurmountable technological barriers to the use of 100% SAF to power planes.

Electric engines could be another weapon in the arsenal against climate change. Rolls-Royce created the engine for the fastest electric vehicle on earth, the "Spirit of Innovation" (pictured above). It has now broken five world records, proving that electric planes are viable—at least when it comes to one-seater craft.

Creating larger electric jets for the mass market will be tricky for several reasons. First, electric engine batteries have to be quite large and quite heavy to power a big plane. Usually that limits their suitability to narrow-body jets and limits their reach to around 100 nautical miles (about the distance between New York City and Miami). Plus, as with electric cars, it's all about the charging stations, and those are currently pretty much impossible to come by at airports.

That could be changing, however—at least in Norway, which is already transitioning to all electric ferries and seems amenable to creating similar infrastructure at airports. If Norway can provide a good model for regional use of electric planes, the rest of the world might follow.

Implementation Plans: Unclear. Most cities don't have strong enough electrical grids to support charging large volumes of aircraft. Additionally, extreme temperatures can affect the life of a battery—an engineering problem that still needs to be solved. Rolls-Royce says it can have electric motors and batteries available for sale by 2026, but it's unlikely we'll see fully electric planes on runways that soon.

What might appear first are hybrid planes that use some battery power, such as for taxiing on the runway, while relying on traditional fuel for most of the flight. But even a small shift like that could save on fuel; taxiing on electric power alone could save 4% of the fuel needed for a flight. Rolls-Royce expects to see this type of hybrid operating by 2030.

Hydrogen has had a bad name in aviation ever since the 1937 Hindenburg disaster, when a massive airship caught fire and exploded, killing 35 people. But today's engineers think hydrogen could have its uses, especially since it produces much fewer carbon emissions than regular jet fuel.

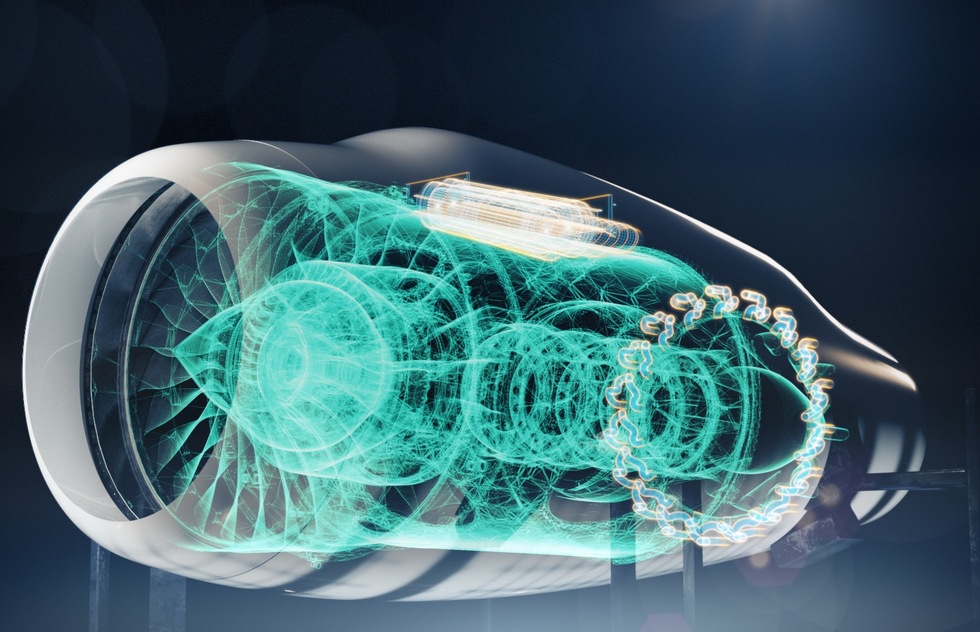

The artist's rendering above shows what a hydrogen engine might look like, though the technology is still in the proof-of-concept stages. Still, there's excitement around the possibilities: European airline EasyJet has announced a partnership with Rolls-Royce to develop hydrogen combustion engines.

Implementation Plans: This type of engine is not expected to be used in airplanes until the mid-2030s.

In 2016, Rolls-Royce began work on creating stronger, more long-lasting turbine parts. It wasn't an easy task. There are 90 to 100 blades per engine, and when a plane is flying, each of these sustains about 18 tons of pressure, rising to a temperature about half as hot as the surface of the sun. That meant many blades had to be replaced after just 100 hours of flying.

But engineers have devised new blades made from a stronger substance that can last 2 to 4 years before needing replacement. That's good for the earth because it means less mining for precious metals such as titanium. Not to mention fewer trucks and ships transporting ore from mines to factories.

What’s the science behind the new blades?

Imagine a sandcastle. Grains of sand by the multitude make up that structure and are held together by moisture. A sheet of metal is similarly composed, with countless molecules of varying shapes and sizes cohering as one.

But just as it’s easy to knock down a sandcastle, cracks can form in metal turbine propellers at high temperatures and under extreme pressure. Rolls-Royce engineered a solution that forces all the molecules into the same shape and direction. This new structure is called a crystal. Repeating and re-creating one crystal type decreases the space between molecules and creates a boundary not easily penetrated.

Implementation Plans: This technology is already being used for new engines and replacement parts for older engines.

Other engine innovations include the individual QR codes that are now attached to every piece of an engine (that's roughly 30,000 parts). The QR codes, along with tiny, AI-monitored cameras installed inside planes, allow Rolls-Royce to be proactive about identifying problems before they become dangerous.

On the sustainability front, the system lets the company be more precise about only fixing or replacing parts that are actually broken, thus saving millions of dollars as well as preventing unnecessary mining.

That's the key question, and I'd be foolish to pretend I have the answer.

But do we have any other choice but to innovate our way out of this crisis?

The vast majority of people do not want to go back to a pre-industrial lifestyle. In order to keep the benefits of our modern lives—and I'd count travel as the biggest one of those—we'll need to do the hard work of living in a more sustainable fashion and we'll need to support the scientists and engineers who are reimagining the systems and machines that prop up today's societies and economies.

If we can do that, and if we can get our governments to do more to support green energy programs, maybe we'll have a fighting chance.

Emily Dickinson wrote that "Hope is the thing with feathers." Perhaps it has wings and engines, too.

Pictured above: Historic engines on display at the Rolls-Royce Museum in Derby, England