To grasp the huge role that emigration has played in Irish history, consider this statistic: While the number of people who have Irish ancestors is thought to be somewhere between 50 and 80 million worldwide, the number of people currently living in Ireland (whether in the Republic of Ireland or the U.K.’s Northern Ireland) is less than 7 million.

The story behind this diaspora is an often sorrowful one, involving desperate folk facing hunger before departure and discrimination upon arrival elsewhere—or, in the case of the penal colonies of Australia and New Zealand, involuntary exile. The saddest chapter would have to be the Irish Potato Famine of 1845-49, when a fungal blight struck the rural poor’s main source of food and more than a million people died of starvation and related illnesses.

Something like 1.5 million others relocated to North America and Britain. As a character puts it in Irish-Canadian author Emma Donoghue’s novel The Wonder, set in the Midlands a few years after the famine: “Ireland, an improvident mother, seemed to ship half her skinny brood abroad.

A Memorial and a Museum

In the Dublin Docklands, a haunting memorial pays tribute to those lost. Lined up along the River Liffey, a grouping of gaunt statues appears to be marching toward the Irish Sea and the wider world beyond.

(Part of the Famine Memorial; photo by the author)

Not far away, EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum, which opened in 2016, tells the tale of Irish dispersal at greater length, using high-tech graphics, maps, and interactive videos to highlight real-life narratives of those who made the crossing, whether during the famine or in the decades afterward. While acknowledging the suffering that goes along with leaving a homeland behind, the museum doesn’t dwell on the sad stuff. In fact, the majority of the exhibit is devoted to celebrating the contributions of Irish immigrants and their offspring around the world.

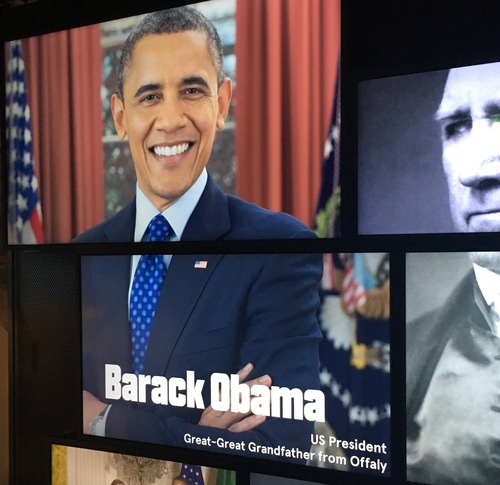

In separate rooms dedicated to every conceivable field of human endeavor—government, science, the arts, sports, and even crime—slick displays illustrate the dissemination of exports such as Irish pubs, Irish step dancing, Irish storytelling, and Irish alcohol guzzled at St. Patrick’s Day celebrations held everywhere from Boston to Tokyo.

Among the multitudes of Irish-descended notables singled out for special mention in the form of photos, artifacts, and touch-screen bios: Broadway pioneer George M. Cohan, birth control activist Margaret Sanger, Wild West outlaw Billy the Kid, dozens of writers, and no fewer than 22 U.S. presidents including Barack Obama, whose great-great grandfather came from Offaly. (Still, there are some baffling omissions: Good luck, for instance, finding Eugene O’Neill, easily the most important Irish-American playwright who ever lived.)

(Display at EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum; photo by the author)

Inevitably, the breadth of the museum’s focus precludes any chance for much depth. But it’s hard not to leave the place feeling that the sons and daughters of Erin have proven uniquely successful when it comes to turning tragedy at home into triumph abroad.

Researching Your Own Irish Roots

If you’re an American, it’s possible that you and your family are part of the legacy of Irish immigrants (others settled in the U.K. or were sent to Australia or New Zealand, often for nonviolent offenses such as political agitation or stealing food). While you’re in Dublin, you can research your Irish roots at the Irish Family History Centre, located in the same building as EPIC.

For a fee, you can access a bank of computers where you can do some digging into Irish birth, marriage, and death records—though to be honest, there’s not a lot here that you can’t find on your own laptop. Each ticket does, however, include a one-month subscription to Findmypast (a U.K.-based service said to have a richer trove of Irish records than competitors such as Ancestry.com), which might prove useful. The Irish Family History Centre also offers half-hour and hourlong consultations with genealogy experts at an additional charge.

You could always hire a private genealogist to look into your family tree, too, but if all this is starting to sound expensive, don't worry: There’s a lot you can do on your own, both before and during your trip to Ireland.

AT HOME

The most important task to take on before searching archives overseas is to locate your immigrant forebear—i.e., the one who left. Go ahead and join a subscription genealogy service to get the ball rolling if you want, but keep in mind that not all records are online, particularly for small municipalities where ancestors might have lived. A good place to start is the free-to-use Family History Research Wiki, where you can enter your state or county and get exhaustive step-by-step instructions for retrieving government records and other information for where you live.

Additionally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (of all agencies) maintains a handy free index of where to write for vital records anywhere in the United States.

Don’t forget to consult your own personal archives, too: family photos, letters, obituaries, Bible inscriptions, the memories of older relatives, and so on. Start a website or Facebook group so that siblings and cousins can collaborate on the project.

IN IRELAND

Once you’ve identified an Irish immigrant in your family’s past, you can begin to trace his or her life and origins on the Emerald Isle. In Dublin, the main repository of records for the entire country is the General Register Office, which has a family research facility on Werburgh Street where visitors can scour the archives for a daily fee. Your detective work will likely run into obstacles, however, as you approach the middle of the 19th century. Digitized birth, death, and Catholic marriage records only go back to 1864, non-Catholic marriages to 1845.

Another avenue of inquiry, which might stretch back further in time, is church records. Several Roman Catholic dioceses in Ireland have made those searchable online (sometimes extra fees apply), though the data tends to be hit and miss because you’re at the mercy of what the priest saw fit to jot down—sometimes that might include, say, the names of a groom’s parents, but not always. Digitized Protestant records are scarcer, but in the 19th century, Ireland’s poor were predominantly Catholic, and the poor were the ones who emigrated. If you manage to discover the parish where your Irish ancestor attended church and you want to have a look at the register, it’s considered good manners to leave the church a donation of at least €10 (US$12).

As you can see, there’s a lot of work to be done and several fees to be paid on the way to solving the mystery of who you are and how you got here. What starts out as filling in a family tree can turn into a multigenerational saga spanning oceans, continents, and centuries.