Explore Latino L.A.'s Food and Culture, from Olvera Street to Boyle Heights

By Zac ThompsonIn a way, Los Angeles is the capital of rural Latin America. According to the Census Bureau, almost half of L.A.’s population is Latino, and many of those residents came from (or descended from forebears who came from) tiny villages in Central and South America. Over time, these immigrant communities have reshaped neighborhoods in the big city, particularly on the east side, to echo the small towns they left behind.

Urban planner and East L.A. native James Rojas calls this “Latino Urbanism”—a term he coined 30 years ago after studying his neighborhood’s elaborately decorated lawns, complete with fountains, shrines, and archways. “Everything you’ll find in a plaza in Latin America,” he tells us, “is in a front yard in East L.A.” Murals, markets, thoroughfares, and other public spaces throughout the city likewise bear the imprint of Latinos, starting with the oldest parts of the city. For visitors, these sites help give a fuller picture of L.A.’s history and culture, provide some pedestrian-friendly street life to dispute the city’s car-centric reputation, and honor the contributions of a group who have been here from before the start. Says Rojas: “What you create becomes your struggle, your survival, your identity, your power.”

Pictured: La Ofrenda, a mural painted by Yreina Cervantez to pay tribute to union leader Dolores Huerta. It's located under the First Street Bridge, at Toluca Street.

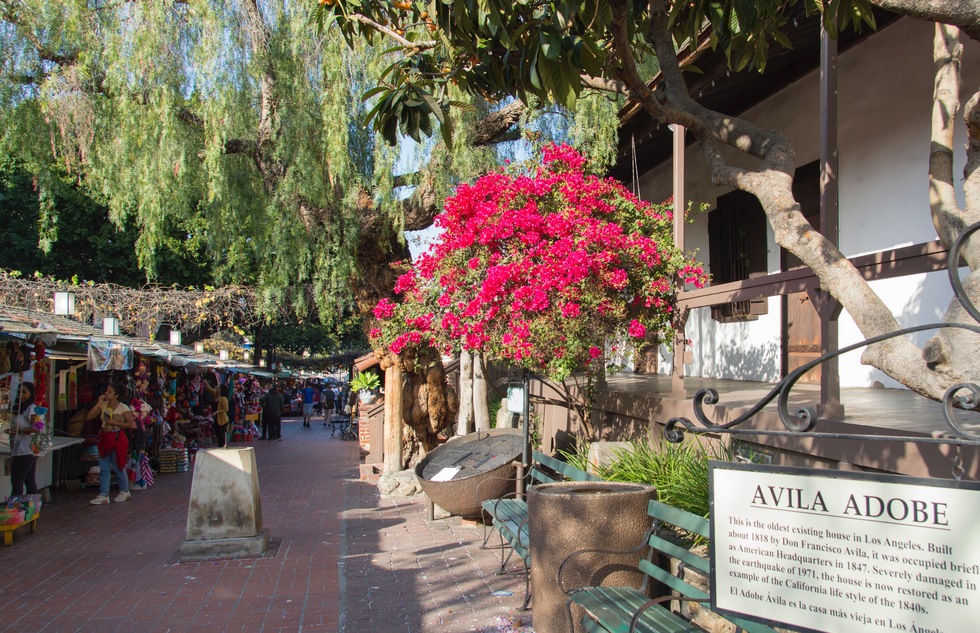

The area where 44 settlers with Spain’s backing founded Los Angeles in 1781—the original name was El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciuncula, which would have been hard to fit on souvenir key chains—is now known as El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument (125 Paseo de la Plaza) in the northern part of Downtown. Centered on the Old Plaza and encompassing numerous museums, murals, and the city’s oldest buildings (including the oldest house, Avila Adobe, built in 1818 and pictured above), the district is a nostalgic, tourist-focused evocation of Old Mexico (Rojas calls the style “Chicano Utopia”). But its roots in the past are genuine and palpable at spots like La Placita church (535 N. Main St.), established in the early 19th century and dedicated in recent decades to protecting refugees and immigrants.

El Pueblo’s primary draw is Olvera Street, a brick-paved pedestrian thoroughfare that serves as the setting for a lively Mexican-style marketplace. Colorful stalls sell snacks like chocolate-filled churros as well as handicrafts including pottery, leather goods, masks, and folk art. The swirling ambience of the place kicks up a notch or two on weekends and holidays such as Mexican Independence Day (September 16), when you’ll encounter strolling mariachis and traditional dancers. No matter when you visit, though, a stop at Cielito Lindo (E-23 Olvera St.) is required. The stand has been serving up freshly made, mouth-watering taquitos with avocado sauce since 1934.

Just south of La Placita church stands the Vickrey-Brunswig Building (501 N. Main St.), home of LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes. Here, visitors can learn all about L.A.’s Mexican and Mexican-American history and identity via interactive, bilingual exhibits (like the one pictured above) containing videos, artifacts, a detailed replica of a Los Angeles street in the 1920s, and, perhaps most valuable of all, video testimonials from Latino residents of all ages telling their stories in their own words.

Not far away, the ghostly remains of América Tropical, painted in the 1930s by seminal Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, overlooks the western side of Olvera Street. At one time covered with paint at the request of Anglo Angelenos who objected to the work’s angry critique of imperialism, the mural was eventually restored and put back on display in 2012. It’s hard to make out much of the colonial violence on the faded wall painting today, but a small interpretive center helps put the art, the artist, and the political climate of the time in context.

On the southern end of Downtown L.A., amid factories and wholesalers along East Olympic Boulevard near South Central Avenue, you’ll encounter far fewer tourists than on Olvera Street in an area nicknamed the Piñata District. A clump of party supply stores here stocks an eye-popping array of candy-stuffed effigies representing flowers, musical instruments, soccer balls, foods, a menagerie of animals (from butterflies to dinosaurs), and human figures such as clowns, cowboys, and Frida Kahlo, whom we have no interest in beating with a stick, thank you very much. There are also rows upon rows of candy, often in surprisingly spicy flavors, for filling your papier-mâché whatsit. Out front, vendors cook Mexican and Salvadoran street food staples like pupusas and fried plantains.

To see the kind of streetscapes that Rojas highlighted in his Latino Urbanism research, head east of Downtown along Cesar Chavez Avenue to reach Boyle Heights, where many residents have retrofitted their neighborhood with Central and South American features such as impromptu shrines, storefronts adorned with colorful pictograms indicating what’s sold inside, and front yards that serve as village plazas. “Everybody contributes to the landscape,” says Rojas. “That 5-year-old walking to school, the woman selling tamales—it’s all part of the same community.”

As Boyle Heights gentrifies, however, tensions have arisen between longtime inhabitants and newcomers over zoning issues and affordable housing, so visitors should be respectful, especially in residential areas. For popular public spaces, try Mariachi Plaza (pictured above; it's at the convergence of E. 1st St., Boyle Ave., and Pleasant Ave.), where costumed musicians hang out, waiting to be hired by restaurants and party planners. Afterwards stop by Birrieria De Don Boni (1845 E. 1st St.), a culinary mainstay specializing in Jalisco-style goat stew.

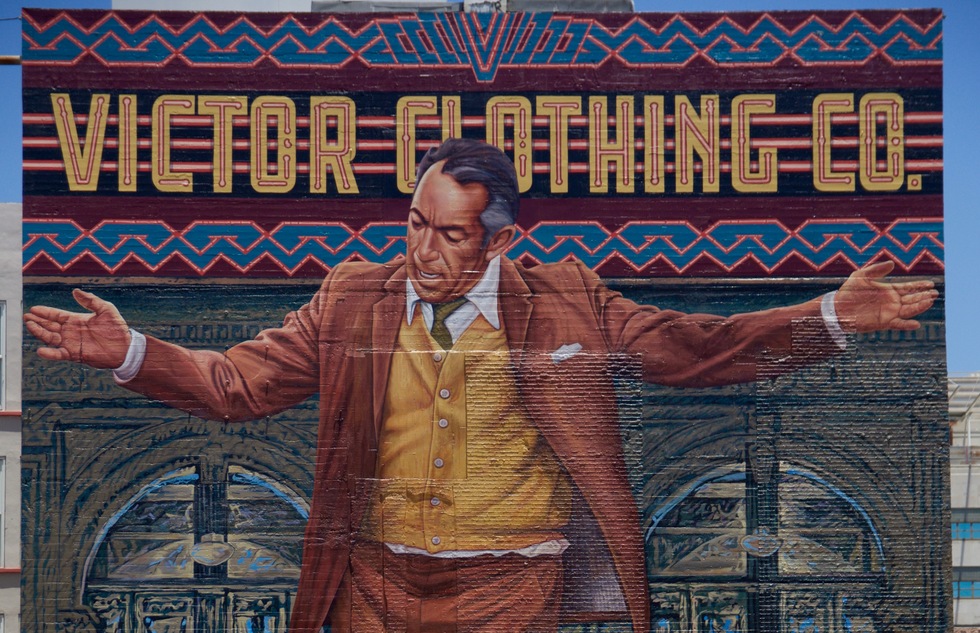

“The whole idea of using murals as a way of telling stories and to celebrate your community is really important [to Latinos],” says Rojas, “and that comes from the early Spanish and their efforts to communicate with native populations.” Conveying political and aesthetic ideas through giant graphics was later adapted by the great Mexican muralists such as Diego Rivera and Siqueiros, and then the practice flourished in Los Angeles—though there have been setbacks over the years due to city ordinances targeting graffiti.

Classics of the genre include We Are Not a Minority, Mario Torero’s 1978 tribute to Che Guevara in Boyle Heights (Estrada Courts, 3217 W. Olympic Blvd.); Willie Herrón and Gronk’s nearby 1973 Moratorium: The Black and White Mural, which memorializes a police attack on Chicano antiwar protestors (Estrada Courts, 3221 Olympic Blvd); and, Downtown, The Pope of Broadway (pictured above), Eloy Torrez’s 70-foot-tall portrait of Latino film star and East L.A. native Anthony Quinn (Victor Clothing Company, 240 S. Broadway). The mother of all murals is Judith Baca’s half-mile-long The Great Wall of Los Angeles along a drainage channel in Valley Glen to the northwest (12920 W. Oxnard St.). The epic work tells the story of California from dinosaurs to Baby Boomers.

Fresh murals are going up all the time on store facades (often, though not always, with the owners’ permission), highway overpasses, empty lots, community centers, and other concrete canvases across town. One of the most prolific teams of artists in recent years has been El Mac and Retna, who have created oversized, silvery-sheened photorealist faces in western Culver City (Of Our Youth, 3030 La Cienega Blvd.), Downtown (Blessed Are the Meek, pictured above, which also features contributions from Estevan Oriol; it's at 529 E. 6th St.), and elsewhere.

To find murals, you can search by title, location, artist, or subject matter in the online directory kept by the Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles. But street art is by nature transitory, so a better way to catch sight of some here-today, gone-tomorrow masterpieces is by booking a tour of Downtown’s Arts District from Cartwheel Art Tours, which offers several experiences unlocking L.A.’s secrets.

A marketplace in rural Mexico is all-encompassing—not just with regard to the goods on sale, but also the opportunities for socializing and entertainment. Opened in 1968, El Mercado de Los Angeles (at the corner of First and Lorena streets) has been providing a similar experience for generations of Boyle Heights residents. You can buy everything from carnitas to cowboy boots at this multilevel mall, affectionately nicknamed El Mercadito. While you shop, snack on buñuelos (sugar-dusted discs of fried dough) or fruity sweets, before heading up to the top floor to watch mariachi bands serenade restaurant diners with traditional tunes. On your way out, don’t forget to pay your respects at the large shrine to the Virgin of Guadalupe in the parking lot.

In Plaza Mexico, the Los Angeles area has a kind of south-of-the-border theme park. Located in Lynwood (about 15 miles south of Downtown L.A.), the shopping, dining, and entertainment complex features a large open-air square and Spanish colonial architecture recalling Mexican towns. What’s more, the outdoor space is dotted with replicas of landmarks including Mexico City’s Angel of Independence statue. Built by Korean investors, the plaza has become popular with Latino families not only for its authentic restaurants, concerts, and stores, but also for the cultural outlet it provides for the homesick. “A lot of immigrants who can’t go to Mexico,” says Rojas, referring to legal and economic obstacles, “take their kids to Plaza Mexico to show them what life is like there.”

It’s yet another bridge that L.A.’s Latinos have found between their points of origin and where they ended up.