Best Places 2021: Great Authors on Our America

By Frommer's StaffWe invited some of the most celebrated authors in the United States to tell us about their America. These top-tier writers and storytellers had free rein to select the destinations that they think define the United States and that shaped the nation they love. This year’s Best Places names the spots Americans should get to know—one day, once the pandemic is just a bad memory—to better understand their own heritage and legacy and, perhaps, to start the process of healing.

These thoughtful mini-essays by some of today’s greatest communicators make for a compelling, often personal, and moving portrait of the United States.

As a result, this year’s Best Places list is not a shopping list for immediate dream vacations. It’s a collection of essential destinations for creating a more perfect union.

Before making future plans for any of the places below, check their websites for temporary closures affecting interior spaces, tours, and amenities. In some cases, you may need to make advance reservations for timed entry.

Jump to each writer's essay:

Gloria Steinem: Serpent Mound Historical Site, Ohio • Daniel Okrent: Ellis Island, New York City • David Sedaris: The Little America Hotel, Salt Lake City • Jodi Picoult: Black Heritage Trail in Portsmouth, New Hampshire • Lydia Millet: Avra Valley, Arizona • Sahar Mustafah: Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan • Cheryl Strayed: The Oregon Coast • Susan Choi: Manzanar National Historic Site, California • Timothy Egan: Acoma Sky City, New Mexico • Arthur and Pauline Frommer: Independence Hall, Philadelphia • Kim Johnson: National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama • Rick Atkinson: Washington, D.C. • Margaret Verble: Fort Gibson, Oklahoma • Fannie Flagg: Solvang, California • Dar Williams: Detroit • TaraShea Nesbit: Hanford Reach National Monument, Washington State • Cathleen Schine: The Kinney-Tabor House in Venice, California

Because we may still have in the back of our minds a grade school teaching that Columbus "discovered" America or that our own relatives left Old Europe for the New World, we often still think of North America as a young continent, as if it had been somehow innocent of inhabitants until our own relatives showed up.

In fact, current theories and discoveries push this living history back at least 30,000 years. There are still some remaining human-made features of the earth—for instance, the Serpent Mound in Ohio and earthworks in the Southwest—that speak to generations of devoted labor and the constructing of both burial sites and astrological markings that were feats of engineering and labor on par with, and often earlier than, the Pyramids of Egypt.

Yet even though I grew up in southern Ohio, I heard nothing about the famous Serpent Mound that is about a quarter of a mile long. Like most of the earthworks in North and South America, this was probably either an astrological sign, a burial site, or both. Others were leveled or looted before they were understood and protected, and some have been obscured by residences and parks, but more are being preserved and valued as testimony to a living history that predated writing and are now being written about. The New World is also the Old World.

Many Native Americans have grown up knowing this from stories passed down orally, and more arriving Americans are beginning to discover an ancient and new home.

Gloria Steinem is a writer, political activist, and feminist organizer. She was a founder of New York and Ms. magazines, and is the author of The Truth Will Set You Free, But First It Will Piss You Off, My Life on the Road, Moving Beyond Words, Revolution from Within, and Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions, all published in the United States, and in India, As If Women Matter.

There’s something ironic about Ellis Island. I can think of no other place that is so deeply American, but not one of the souls who passed through it between 1892 and 1954 was in fact an American. This gateway to our nation, poised on the edge of New York Harbor, marked the beginning of some 12 million journeys that helped make our country what it is today.

The historic preservation and renovation of the island and its buildings, completed in 1990, is a model of the form. As you stand in the soaring Registry Room, where (as Emma Lazarus’s poem had it) “your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free” first gathered on American shores, you can’t help but marvel at its restored beauty. But if your ancestors once stood in long lines in this magnificent space (now the central element of the island’s National Immigration Museum), you might also conjure up mental images of strangers in a new land, probably in somewhat ragged clothing, carrying everything they owned in battered suitcases. They, however, could not have possibly imagined you, their descendant, now as fully American as anyone whose family has been here since the Mayflower.

On nearby Liberty Island, that glorious statue reminds us of a welcoming America. But Ellis Island is evidence that the welcome was, in fact, the barest beginning of millions of American stories.

Daniel Okrent was a finalist for the 2004 Pulitzer Prize in history. His most recent book is The Guarded Gate: Bigotry, Eugenics, and the Law That Kept Two Generations of Jews, Italians, and Other European Immigrants Out of America.

If you want to understand something about the U.S., you must stay at the Little America Hotel in Salt Lake City. I liken it to a five-star motel, the only one in the world. A tower was added to the original two-story part but it still feels intimate. The rooms are a bit dated, but lovingly cared for, and huge. Many of the hotel guests and visitors are Mormons. They all seem to have eight kids but do those children run unchecked through the lobby? Do they take joyrides in the elevators or put their feet up on the furniture? No they do not. Every child at the Little America is well behaved. Every. Single. One. Figure that out, why don’t you!

There’s a restaurant in the hotel but I prefer the coffee shop. It feels like the merriest place in the world, let alone the U.S. Go on prime rib night and save room for pie. Listen to the people at the surrounding tables. They’re not just conservatives, they’re squares, many with some pretty out-there religious beliefs. And they’re lovely!

Stop to talk to them on your way out the door. Tell them I sent you.

David Sedaris’s latest book is The Best of Me.

New Hampshire is known for its fall leaves, its natural beauty. . . and its whiteness. Yet the third-least diverse state in America has been home, since 1645, to Africans and African Americans, who contributed heartily to the welfare of their community. The Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail celebrates the more than 700 Black residents who lived in the port city by the time of the American Revolution, and who—like other Black people who helped build this country—have been left out of previous chronicles of the state. Although many believe that abolitionists abounded in New England, Portsmouth—a sales port—was an entry point for the slave trade in America.

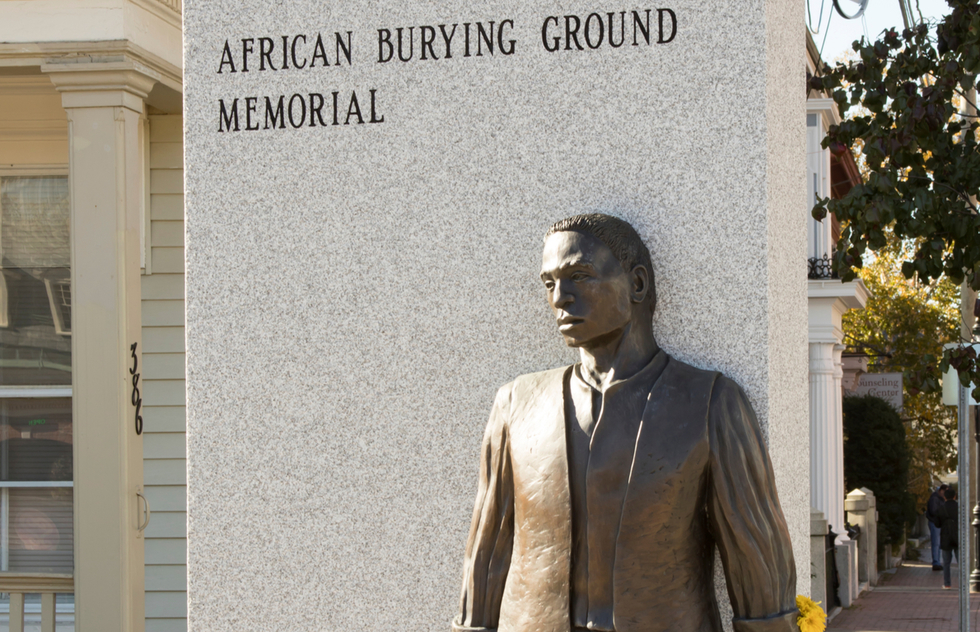

The Black Heritage Trail comprises 24 self-guided stops around town: from the docks where Africans forcibly arrived by ship, to the African Burying Ground, to Stoodley’s Tavern—a place where patriots like Paul Revere gathered pre-Revolution—which a decade earlier was the site of a public slave auction. The Moffatt-Ladd House was home to both General William Whipple—who signed the Declaration of Independence to free the colonies from British rule—and to Prince Whipple—an enslaved African who was eventually freed and who petitioned the state legislature to abolish slavery (a petition that was not granted till 234 years later). Ona Marie Judge, enslaved by George Washington, escaped to Portsmouth in 1796; the Heritage Trail follows the wharf near Prescott Park where she arrived by ship, the church where she got married, and the market where she was spotted—leading to her near-capture.

Sobering and eye-opening, the Black Heritage Trail forces us to question those we have traditionally considered heroes, and to elevate those who have been marginalized instead. It squarely centers Black life in early America, at a time when we as Americans need to be rewriting our history to do so.

Jodi Picoult is a #1 New York Times bestselling author whose most recent novel is The Book of Two Ways.

Outside Tucson, between two lines of mountain ranges, is a sage-green desert where people have lived for thousands of years. On either side of the valley, which is dotted with ancient petroglyph art, lie national parks and monuments. There’s a famous Desert Museum that draws visitors from around the world. To the south and west are the lands of the Pascua Yaqui and Tohono O’odham.

I live in the Avra Valley, in a house surrounded by giant saguaros, the iconic cacti that stand like people with their arms raised in welcome. Groves of prickly pear and cholla cactus whose spines are turned gold by the setting sun, thorny palo verde trees with green bark that bloom in dense clouds of yellow. Bobcats pad silently through my yard, along with skittish mule deer and herds of snuffling, boar-like animals called javelinas. Elusive ringtails and pink-and-black Gila monsters hide in the scrub and sand. Hawks and woodpeckers and glittering hummingbirds.

But the state plans to build a freeway called I-11 through the middle of the valley. The pavement and footprint and noise and pollution would mean the end of the wildlife, but also of the life people know. None of us want it, yet the slow scheme marches on. So we’re uncertain of how long our valley will persist—whether the day will come when we’ll have to leave, following the coyotes and foxes and owls.

Lydia Millet is the author of more than a dozen novels and short story collections. Her most recent book, A Children's Bible, was a finalist for the National Book Award and a New York Times Top 10 book of 2020.

Each time I enter the Arab American National Museum, an incredible sense of kinship and belonging washes over me. Off a main city drag, a brightly lit atrium welcomes me and I am instantly captivated by the gorgeous domed ceiling, signaling an architectural marriage of modernity and antiquity. Within its elegantly adorned walls, the space centers the narratives of historically marginalized or often vilified Arab Americans; the exhibits reclaim our stories of ingenuity and perseverance, as well as our service to this country. By the final exhibit, I experience a profound affirmation: Arab Americans are not a monolith. Our fabric is multilayered and colorful, woven into our national tapestry over a century. The AANM is a glittering reminder.

After absorbing the compelling stories of generations who’ve come before me, I embark on a Middle Eastern culinary journey. A six-minute drive from the AANM is New Yasmeen Bakery, a Lebanese deli-style eatery, where I select savory stuffed and open-faced baked breads and spicy kabobs and stews. For dessert, I head to Shatila for warm-served knaffa dripping with syrup, and a piping-hot glass of mint-flavored tea.

Though I am a Palestinian-Chicago native, these Dearborn treasures feel like coming home again and again.

Sahar Mustafah’s novel The Beauty of Your Face was named a New York Times Notable Book of 2020.

Back in the day, our politicians thought it wise to protect the Oregon Coast. I think it's a point of pride that the beaches in Oregon are all considered public beaches. Anywhere you go, all up and down the coast, there's a feeling that this natural wonder belongs to all of us.

One of my favorite towns is at the very far north end of the Oregon Coast: Astoria. It's not what you think of as a typical beach town, because it's situated at the mouth of the Columbia River, so there's a kind of old-school fishing village vibe. There's a great bookstore, a great radio station, and lots of culture. Just outside of Astoria, at Fort Stevens State Park, there's an actual shipwreck on the beach. It's called the Peter Iredale, and it's a cargo ship that ran aground at Clatsop Spit in 1906 and has been left there to slowly sink in the sand. Even as a grown-up, when I first walked on the beach and I saw it, I thought, This is like a child's fantasy! It's like a pirate ship. When the tide goes low, the kids can crawl around on the old rusted-out, skeletal remains of the ship.

I think my three favorite things to do when I travel are walking, eating, and cozying up and reading books. The Oregon Coast is perfect for all those things. There are endless long walks, whether they be on the astounding beaches or on the many trails that zigzag the mountains above the beaches. There are beautiful, fabulous restaurants in all of these villages all along the way. Of course, the weather often is harsh. Even in the middle of summer, you can be bundled up in your hoodie under a hat. It's the kind of weather that makes you want to do your walking and your eating and then cozy up inside by a fire. —as told to Jason Cochran

Cheryl Strayed’s work includes the #1 New York Times bestselling memoir Wild, the bestselling advice essay collection Tiny Beautiful Things, the novel Torch, and the quotes collection Brave Enough.

I was working on my second novel [2003’s American Woman], and I discovered there were all of these—I think the best word is yearbooks of life at Manzanar [one of 10 sites where Japanese Americans were interned during World War II, and a pivotal location in the novel]. The interned Japanese Americans had formed clubs and there were activities and dances and people had gardens. I couldn’t believe it. There were these photos of the Manzanar Baking Club or the Manzanar Garden Club or, like, the sock hop. They had responded in this affirmative way, as if to say, We’re gonna try to make this as much of a chosen experience as we can, even though our lives have been destroyed and we’ve been imprisoned by our own government. It’s a place that’s about the idea of justice and about how to make justice for your community.

To this day, I’ve never been there physically, but I’ve always wanted to go, not just for myself but because it stands for this idea that we have to do better.

Right now, we’re at such a dangerous moment and it feels like we keep getting into greater and greater danger. We’re separating families at the border. There are children who will never see their parents again because of the actions of our government. And we’re paying taxes to support this devastation. I wish that every American could be taken to Manzanar or a place like it so that you could look at what a serious mistake that really damages your nation and your people—what that looks like. And then think, Are we making other mistakes like that right now? You can’t go back and not have Japanese Americans interned, but there are a lot of mistakes we could be fixing right now.—as told to Zac Thompson

Susan Choi’s recent books include Camp Tiger (with illustrations by John Rocco) and Trust Exercise, winner of the 2019 National Book Award for fiction.

It rises out of the New Mexico sky, a visage of beige mud and wind-lacerated stone, nearly 400 feet above the desert floor 60 miles west of Albuquerque. The adobe homes, the clay ovens that look like beehives, the kivas, the plazas, and ladders to the rooftops, are a marvel. For here, on the summit of this big rock, appears something rare in the United States—the continuity of life over centuries.

The immutable evidence of that pulse of life is what gives Acoma its singular place in our history: It is the oldest continuously inhabited place in the United States. The natives of Sky City, one of four communities that make up the village of the Acoma Pueblo, call their home the Place That Always Was. People have lived atop the rock of Acoma for at least 800 years, in the consensus archaeological view. This makes Acoma nearly twice as old as St. Augustine, Florida, which is too often cited as the oldest. Acoma is Plymouth Rock West, where cultures clashed—Spanish and Native—and one is more alive than ever.

Timothy Egan, a New York Times columnist, is the author of nine books. His most recent is A Pilgrimage to Eternity: From Canterbury to Rome in Search of a Faith.

Most visitors know what they’ll see when they visit Independence Hall. What comes as a surprise is what they hear: a layered, often surprising portrait of the rebels and thinkers who signed the Declaration of Independence and created the Constitution that still governs our nation today. These tales are spun by some of the most gifted storytellers in the United States, an elite group of national park rangers who don’t pull their punches when discussing the mistakes the founders made (the acceptance of slavery foremost among them) or the tumultuous nature of the debates that rang off these walls.

The human, messy, sometimes maddening nature of democracy comes alive, as does the power of compromise. We learn that the Framers had very different goals coming into what turned out to be a frenzied four-month-long Constitutional Convention. But they were united in wanting to create a United States, a country where the ideal was balance—a system with so many different actors that no one person or party could amass unfettered power. That balance, that focus on governing together rather than obsessing over who is winning or fixating on the personality of specific leaders, is something Americans need to aspire to once again. Without it we are betraying our founders—and ourselves.

Arthur Frommer is the author of the all-time travel best seller Europe on 5 Dollars a Day and the founder of the Frommer’s guidebooks. Today, he runs the company with daughter Pauline Frommer, an award-winning author in her own right.

In my work with This Is My America, I focused on wrongful incarceration and its connection to historical lynchings and slavery. A lot of my inspiration came from Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow and Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy. Stevenson’s work through the Equal Justice Initiative in Alabama created in 2018 the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

What I love about the memorial is that it actually counts all of these Black lives lost between 1877 and 1950. It’s a place that has a very somber feeling, where people can bear witness to what has actually happened in our country and feel the connection to these generational cycles of trauma that we often don’t recognize come from a long lineage of issues around race and the policing of Black bodies.

[At the memorial,] you’re almost in awe of the massiveness of the pain that’s been experienced. I think about the families of the victims. They have these memorial pieces for every individual hanging from the ceiling. That could have been somebody’s parent. Did they have a child? Who raised that child? And did that child grow up in fear? And how does that trauma pass onto the next person?

There’s a heavy weight to it. But it’s also a feeling of resolution, I guess you could say, because it’s recognized. It’s something you can’t take away. —as told to Zac Thompson

Kim Johnson’s debut novel, This Is My America, was released in 2020.

No, it’s not the Swamp, the Deep State, or even the “city of magnificent intentions,” as Charles Dickens once dubbed it. Rather, Washington, D.C., is a vibrant, vivid, often gorgeous world capital, rich in art, architecture, history, politics—good and bad—and grace notes. To appreciate the latter, I recommend three gardens on the National Mall, with adjacent tourist destinations, and a cemetery.

First, try the National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden, 6 acres of whimsy and genius across the street from the National Archives, where you can pay homage to the original Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Second, stroll through the U.S. Botanic Garden, both the conservatory and two outdoor parks in the shadow of the Capitol; then step nearby to the Ulysses S. Grant Memorial, the fifth-largest equestrian statue in the world and a forceful evocation of the Civil War. Finally, my personal favorite is the Mary Livingston Ripley Garden, a hidden jewel tucked along the flank of the Hirshhorn Museum. From there, it’s a short walk to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the newest and among the most affecting of the Smithsonian Institution’s 19 museums.

Finally, for a visceral understanding of Washington, D.C., as the embodiment of an ideal worth dying for, cross the Potomac River to Arlington National Cemetery. I particularly recommend Section 60, where many of the dead from our most recent wars rest in honor.

Rick Atkinson is a Pulitzer Prize–winning historian and journalist. The first book in his Revolution Trilogy, The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775–1777, was published in 2019.

Fort Gibson has seen more history than almost anywhere else in the West. Located outside of the eastern Oklahoma small town of the same name, it consists of a stockade and several major buildings spread over acres. The original fort was built in 1824 to keep peace between the Osage and the Cherokee and was nearer a rock shelf on the Grand River that made a natural boat landing. That first stockade was also in a thicket of mosquito-infested cane. So many soldiers died from malaria that the outpost quickly became known as the “charnel house of the U.S. Army.”

After the fort was moved away from the cane, it became familiar to many famous people, including Sam Houston (1829), Washington Irving (1832), Jefferson Davis (1834), and Robert E. Lee (1855). More tragically, the Creek and the Seminole people camped around its walls after their forced removals from the Southeast. The fort was also the site of many treaty signings and payments for Indian land. During the Civil War, the site changed hands and fell into disrepair. After several owners, including the Cherokees, the fort was restored in 1937 by the federal Works Progress Administration and the Oklahoma Historical Society, and it continues to be renovated.

Fort Gibson is featured in Margaret Verble’s novels Maud’s Line (a Pulitzer Prize finalist for fiction) and Cherokee America (a Spur Award winner for best western).

I live in Santa Barbara, and I was looking for a place to go to be quiet and to write [2002's Standing in the Rainbow]. So I took a little cottage 55 minutes away, and I fell in love with the town of Solvang. Everything is Danish. It has little windmills, whole Danish-style streets lit up with lights, and then they have Danish days when everyone dresses up in their official Danish folk clothes and they do dancing on the streets. They put up Danish Christmas decorations all over, so it's almost like Christmas all year round. I thought, Why do I love it here? What makes me like it so much? And it dawned on me that everybody was happy. They all had ice cream, they had aebleskiver pancakes, they had all these waffles to eat, and they love to dress up and decorate. Oh, it is so fantastic!

And you know, Solvang also talks about our heritage. In America, people came from someplace else. They wanted to bring a little bit of someplace they came from. It's so cute the way that the Danes have done that and at the same time turned Solvang into a real American commercial town, but they still maintain their Danish identity. And this is hilarious—I actually kept a little apartment up there. When I drive in, I always start to smile. It makes me happy! Somebody—a friend of mine, you know, a jaded New Yorker—said, “Oh my God, it's just like Disneyland.” And I thought to myself, Well, what's the matter with that? I brought my mother and dad up and I have a photograph of her sitting on a bench in the bright colors of downtown, having an aebleskiver and looking very happy. So, yeah. It's a place that I would recommend if anybody is bored or blue, which we all are sometimes.—as told to Jason Cochran

Fannie Flagg is the bestselling author of novels including Daisy Fay and the Miracle Man and Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe, and her screenplay of Fried Green Tomatoes was nominated for an Academy Award. Her latest book, The Wonder Boy of Whistle Stop, was partly written in Solvang.

Detroit has all the ingredients—local pride, spaces for conversation, opportunities for reflection, and a strong connection to its industrial past—for a revival that reflects the innovation and creativity of its residents, and it’s exciting to see.

Woodward Avenue is the wire that conducts electricity, via the arts, university research centers, sports, and restaurants, through the center of new Detroit. Start at the world-famous Detroit Industry Murals at DIA (Detroit Institute of Arts) Museum. Diego Rivera’s murals show us the visual poetry of factory workers who built the city. Continue down Woodward and stop at the beloved Avalon Bakery, where it's bread ovens, not factory forges, that illuminate the faces of local bakers. Then take a tour at the magnificent Fox Theatre and witness how Detroit’s industry and arts have always been entwined (motors are central to the Motown name, after all).

Finally, turn onto the Riverwalk, where planners have channeled public and private wealth into a safe, beautiful space for festivals, running, walking, and even fishing. This dynamic expanse along the Detroit River allows you to look into the city blocks beyond Woodward, all with their own arts collectives, urban farm groups, educators, cooks, DIY renovators, and curators who wake up every morning with the same Detroit pride and determination of their factory-working predecessors.

This is the city that brought us everything from the Model T to Marvin Gaye. When we walk down Woodward onto the Riverwalk, we can be a part of the R-E-S-P-E-C-T that drives the Motor City home to itself.

Dar Williams is a singer-songwriter and author of What I Found in a Thousand Towns: A Traveling Musician's Guide to Rebuilding America's Communities—One Coffee Shop, Dog Run, and Open-Mike Night at a Time.

The Northwest isn’t known for its secret desert installations, but in southeastern Washington State is one of the most visible of the Manhattan Project sites. Strategically placed along the Columbia River for its cooling waters, the B Reactor was the first of a handful of very large and dangerous machines that worked nonstop to build the U.S. nuclear arsenal, leaving behind millions of gallons of nuclear waste. This first cathedral to the atom is now open to the public.

Hanford tells an American story: land used for thousands of years by Columbia River Basin tribes for foraging, hunting, and fishing, encroached upon by white settlers, privatized by investors/farmers, then seized by the U.S. government for war endeavors, and now a place with a quarter trillion dollars in cleanup costs. Low-income earners were hired to do the precarious work that put them most at risk—dumping buckets of radioactive waste, monitoring the nuclear facilities illuminated by the reactors’ brilliant blue (radioactive) glow.

Today, the overall site, half the size of Rhode Island, has become a wildlife refuge. Elk, mule, bobcat, coyote, and beaver call this arid landscape home. Waterfowl, songbirds, and the unique sage grouse fly the often-cloudless skies. The land is sagebrush steppe, but in spring, pink phlox makes a cheery rug on the desert ground.

TaraShea Nesbit is the author of The Wives of Los Alamos, a finalist for the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize, and Beheld, a Publishers Weekly Best Fiction Book of the Year and a New York Times Notable Book of 2020.

I live in Venice, California, famous for its 1950s Beat culture, its artists, its roller skaters and skateboarders, for Muscle Beach, for murals, for its grungy boardwalk counterculture, avant-garde architecture, homeless encampments, and, most recently, for its metamorphosis into a tech haven called Silicon Beach. But there is one house that has been here from the very beginning, when a wealthy easterner named Abbot Kinney decided to build something he called Venice of America modeled after Italy’s Venice—an oceanside recreational retreat for harried Los Angelenos of the early 20th century. There were (and still are) canals in SoCal’s Venice. And on one of them stood Kinney’s house. That house, with its brave and eccentric past, is my favorite spot in Venice.

Kinney had a driver and close friend named Irving Tabor who drove Kinney everywhere. When a hotel would not allow Tabor in because he was Black, both men slept in the car. When Abbot Kinney died, he left his house at Number One Grand Canal to Tabor. But in 1925, the canals of Venice were strictly segregated. Irving Tabor could not live in his own house. So he cut the house into thirds, loaded it onto a barge pulled by mules, and delivered it to Oakwood, the section of Venice where Black workers lived. The Kinney-Tabor House is still there, a charming forest green behind a white picket fence at the corner of 6th and Santa Cruz, all in one piece.

Cathleen Schine is the author of several international bestsellers including The Love Letter and Rameau’s Niece. Her most recent novel is The Grammarians.